Disclaimer: You’re reading this column because you value my input as a journalist who reports on these issues and therefore has a lot of informed opinions. I’m not a healthcare provider, and these responses are not meant to substitute for medical or therapeutic advice.

Are the Boomer Moms OK?

Q: My Boomer mom eats extremely tiny portions of food. I know I need to mind my own plate, but sometimes I can’t help asking if she’s had enough to eat, to which she often says something about “older people not needing as much food.” She is also cold all the time and also says it’s just part of “being old.” I’ve heard my mother-in-law say similar things.

Is it true that older people have smaller appetites? I can’t help but feel like it’s just a guise for restriction and that they are cold all the time because they are hungry! But that might just be my own triggers talking?

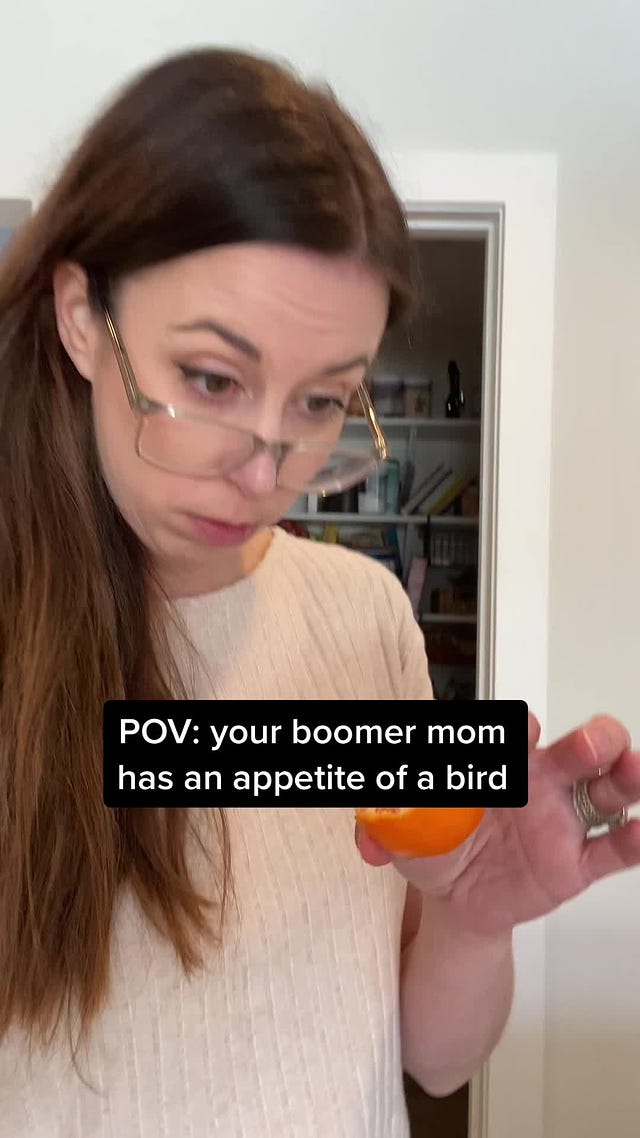

I’m not a doctor and I can’t say what’s happening, exactly, with your mom and her body, or her relationship to food. But I do want to talk more generally about these questions because “my Boomer mom eats like a bird” is a theme that comes up so frequently when I interview Millennials and Gen X folks about their own relationship to food. I think I also got a question about this at every event and interview for Fat Talk. And we see #BoomerMom heavily referenced on TikTok, as part of the larger Almond Mom discourse, of course, but also as its own specific phenomenon. See: Kristen Marie who regularly explores this half a clementine approach to life.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

These videos are funny in a painfully true way—there are so many women, of all ages, rubbing salt off their crackers. But they are also embedded with ageism because they poke fun at behaviors that, if your teenage daughter engaged in them, would not be funny at all. But what we diagnose as eating disordered in thin, white girls, we ignore or reinforce in almost every other population. And so: We have normalized the idea that Boomer women don’t eat. And while I know you’re asking if this should be normal and what to do about it if it isn’t, it’s important to approach these questions with as much compassion as possible. This isn’t about being exasperated with how diety the Boomer moms can be. It’s about understanding why they only feel safe using butter spray in place of real butter; why they still aren’t convinced about eggs; why they might feed other people so joyfully, even aggressively, and yet skip lunch so often themselves. It’s about learning to sit with their discomfort with our own appetites and not internalize it—or repeat that same pattern with our kids’ appetites. And it’s about finding that ever-shifting line for ourselves between compassion and boundaries.

I’ve written before about why the grandparents are not okay, so I won’t unpack the whole history of Boomer diet culture here. (But if you haven’t read that piece, definitely do for context.) Instead, I turned to two wise Boomer women who are more qualified than me to answer these questions: Debra Benfield, RDN, a dietitian who specializes in the intersection of ageism and anti-fatness, and previously joined me on the podcast. And my mom, Marian.

Both Debra and Marian agree that smaller appetites and coldness are common among older folks—and both agree that “common” here doesn’t mean “normal and okay.” “It’s an accepted trope that you gain weight after menopause, and doctors always push weight loss,” Marian says. “Some of us accept the weight gain and some of us return to diet fixes.” My mom and her best friend always know which of their friends are restricting because the portions at their dinner parties are “miniscule.” One of their friends doesn’t exactly restrict portions but does want her kitchen to stay so immaculate that if you bring a dessert to share, she rushes it off to her bathroom instead of letting your dish sit scandalously on her kitchen island. And so she hosts meals where food is framed mostly as an unwelcome interruption. Martha Stewart has been a complicated role model for Boomer women on a lot of levels.

Debra confirms that “metabolism decreases, especially as we pass the 60-year mark, regardless of our activity and body composition.” But she adds: “It is also true that one of the biggest contributors to lower metabolism is not eating enough to meet our bodies’ needs.” At the core of this, of course, is anti-fat bias and ageism, again. Because menopause-related weight gain is framed as a failure and a fate to be avoided at all costs, Boomer women are vulnerable to diet culture mandates to eat less, in much the same way postpartum women are told that “getting our bodies back” should be our number one priority. “I just want to feel like myself again,” is what we say as we embark on a new workout plan or stop eating carbs again, at both of these life stages. But what if we didn’t tie our understanding of ourselves so closely to appearance? What if we were allowed to change as people and as bodies, and not experience that as “letting ourselves go?”

These aren’t easy questions to answer because, as my mom points out, so much of the pressure around weight loss post-menopause comes from the healthcare system. “So many doctors are fine just putting you in the ‘senior box,’” Marian says. “That means hearing over and over that you need to lose weight to get your blood pressure down and avoid diabetes.” For a deep dive into why weight loss isn’t an evidence-based or health-promoting prescription for either of those concerns, check out

’s reporting on how dieting can increase hypertension and insulin resistance, as well her work on weight-neutral, non-restrictive approaches to blood pressure management and blood sugar management.On the “why are Boomers always cold” question, both Debra and my mom pushed back a little bit. “I’m always way colder than your family,” Marian texted. “The older you get, the more you seem to need sweaters when younger people don’t.” Debra says this “is a symptom of a lower metabolic rate,” which may just be a byproduct of aging. “There are other potential contributors like changes in circulation, medication side effects and symptoms of other disease processes,” Debra explains. “Restriction may or may not be a contributing factor.”

So maybe we set the cold thing to one side (and turn up the thermostat a little bit when they visit). But if you’re really worried about how little your mom eats, you can tell her. “Speaking up and expressing love and concern is worthwhile regardless of age,” says Debra. “It is never too late.” You are right to avoid a critique of her eating habits, which will just make her defensive. But you can start by talking more broadly about how much you hate the messages we get to eat less as we age. Share what you are learning about the harm of diet culture and anti-fatness. Ask her about her experiences of ageism, about the messages she gets about her body. Be a safe place she can vent, instead of another person for whom she has to perform her body and her eating habits.

I know that’s likely complicated by the way your mom’s body commentary makes you feel about your body—because for many mothers and daughters, that all gets woven together. But start teasing apart the strands. Model your own unapologetic love of food. And if she balks, maybe that’s your moment to say, “Eating this way brings me a lot of joy, and I worry when I see you depriving yourself. Because I think you deserve this kind of joy too.” She might shut it down, but she also might surprise you. “You are never too old to heal your relationship with eating, movement and you body,” says Debra. “Our hearts and brains are capable of change until the very end.”

For more on this:

PS. Debra is offering a free online workshop on aging with body liberation — today at 12pm ET.

You Asked: Is the AMA finally renouncing BMI?

Last week at its annual conference, the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates voted to adopt a policy naming a whole bunch of problems with BMI — that it has a history of causing harm, that it has been used for racist exclusion, and that “BMI cutoffs are based primarily on data collected from previous generations of non-Hispanic white populations and does not consider a person’s gender or ethnicity.”

When I first saw the headline, I thought, “Holy shit, did we do it?!” A mainstream medical organization denouncing BMI is the essential first step towards the weight-inclusive paradigm shift we so desperately need here (and everywhere).

But then I read the rest of the press release, and realized: We did not do it. In fact, we might now be making things worse.