So, What About Processed Foods?

Nothing about your sense of self-worth needs to change in relation to how many Cheez-Its you eat.

Q: I love the idea of intuitive eating, but wonder how it works with modern processed food which is designed to keep us eating more and more? I have heard that processed food hijacks our bodies’ natural impulses and that sugar and white flour are addictive. I am especially interested in this question as I get ready to introduce solid food to my baby.

Here is a list of the modern processed foods in my house right now: Uncrustables, Eggo pancakes, peanut butter M&Ms, Chips Ahoy cookies, Cinnamon Toast Crunch, Tostitos, Bugles, two kinds of Cheez-its, some Walmart-brand cereal that is chocolate and peanut butter flavored, and those chips that look like tortilla chips but are made with popcorn.

Oh, and Larabars, Stonyfield yogurt, graham crackers, Ritz crackers, Nature’s Bakery fig bars, Quaker Chewy granola bars and quite a lot of cheese (I’m not actually sure if cheese by itself fits the “modern processed” category, but some of this is the kind that comes pre-sliced so probably yes?). I’m sure there are a few I’m forgetting because Dan does our Wal-Mart shopping.

Even as I write what is clearly going to be a defense of modern processed foods, I feel compelled to add that we also have at least five kinds of fruit and a crisper drawer full of vegetables, plus a garden with more outside. I feel further compelled to note the multiple layers of privilege that enable us to have all of this food—berries and Bugles, Goldfish and leafy greens. My children have never known food insecurity, whether from poverty or dieting. They take for granted that we have a snack shelf full of options.

And as a result, I cannot pay them to eat most of those foods.

Don’t get me wrong: We’re actually out of one of our most important processed foods right now—Goldfish crackers—and my 3-year-old had a hangry meltdown after camp yesterday when she realized this. It took about 15 minutes of yelling for her to accept an alternative snack in the form of snap pea crisps. I understood her pain. I felt similarly once when Dan bought white cheddar Cheez-Its instead of Extra Toasty and I thought, Well. This is how our marriage ends.

Part of the reason we have so many processed foods in the house is that everyone feels passionately about a different one. And in the case of my kids, especially, that particular beloved processed food changes every few weeks or months when they get bored of it. Before Goldfish, the toddler was obsessed with popcorn and then Larabars. My older child snacks on Cinnamon Toast Crunch right now, but before that it was Ritz crackers, then snap pea crisps, then M&Ms, then fig bars. These shifts usually happen right when we buy the largest possible container of what was the current favorite but is now dead to them. This giant bag or box of the rejected food then sits in our pantry for months until I think to serve it at a party or (sorry, sorry, sorry, I also hate food waste) toss it out.

I want to be clear: The victory here is not that my children turn down processed foods. The victory is that they don’t feel out of control around these foods. They don’t feel compelled to eat them just because they’re there—which is what everyone assumes will happen when you have a mountain of processed foods on hand.

My own experience has been similar, though less effortless. Back in my dieting days, I used to only “allow” myself to have Cheez-Its on road trips (I guess because gas stations usually sell them?). I would then eat a whole box over the course of a day in the car. Even after I stopped dieting, it took awhile to feel like this was a food I could keep in the house unless we were having people over. But once the pandemic hit (no road trips, no parties) they earned a permanent spot on the grocery list. And yes, in the beginning, it was so exciting to have them around—they were literally the most exciting thing about many a day in lockdown—that I ate a lot of them, and so did my kids. But after a while, that changed. I still eat some most days as an afternoon snack, but it feels much more relaxed. Some days I don’t eat them and I don’t think about it. On days when I haven’t had time to eat a real lunch, I eat a lot of them. The best part is that nothing about my sense of self-worth changes in relation to how many Cheez-Its I eat.

Your mileage may vary, of course. If you grew up with lots of explicit or implicit rules around good and bad foods, or if your family couldn’t afford the foods you most wanted to eat, it makes total sense to feel compelled to eat a lot of those off-limits foods whenever you get the chance. “When I was younger, my fixation on eating more and more originally stemmed from hunger. I was restricted in terms of my diet because I have always lived in a fat body, at any age,” says Marquisele Mercedes, a writer and public health scholar from the Bronx who I interviewed for an audio newsletter a few weeks ago. Mercedes says she fixated on the foods she wasn’t allowed to eat. “And eventually, that fixation moved away from something that felt physically necessary and became more a compulsion that I had to fulfill. Because if I didn’t have it, it meant that I had let some kind of need go unfulfilled. And that caused me a lot of distress.”

But here’s an interesting twist: “I didn’t become fixated with ultra-processed food. That wasn’t the thing I really even gave a shit about,” Mercedes says. “When I was a kid, I was like, I want to eat more of the food that I had for dinner, because I was still hungry. And I live in this body, and my body is telling me that it needs food.”

When we read about how “ultra-processed foods” are formulated specifically to “hook” us with their heightened levels of salt, sugar and fat, we almost never hear about this piece of it. Yes, these foods are designed to taste very, very good. But your emotional relationship to that food is much more about access and permission than it is about flavor. This is even true of all those rats in the studies that show sugar acts like cocaine on their brains: It only has that impact after they starve the rats. (Research summary here but CW for triggering language.)

We see the same in human research, says Christy Harrison, MPH, RD, a dietitian, journalist and author of Anti-Diet who is joining me for this Thursday’s audio newsletter. “Chronic dieters do eat more in the presence of highly palatable food. They’re also more susceptible to food advertising, and we see more brain activity in response to sweet foods. But people who are not restrained eaters do not show the same response. Their pleasure centers still light up, but there isn’t this immense reward in their brains, because they haven’t experienced that immense deprivation.” (The research Harrison is referencing can be found here and here, but again, CW because scientists seemingly cannot talk about food or weight in non-stigmatizing ways.) All of this makes sense because sugar is not cocaine or heroin. Glucose, like water, is a substance critical to our survival. You can’t be addicted to water, but you sure want to drink a lot of it if you go awhile without any.

In addition to its physiological necessity, we have an emotional need for food. As Lisa Du Breuil, a psychotherapist who treats patients with eating disorders at Massachusetts General Hospital and in private practice in Salem, MA, told me when I wrote The Eating Instinct: “Sharing meals is probably our best way to bond and connect, other than sex. It doesn’t make you an addict to miss that. It makes you human.” Du Breuil also uses the phrase “Abundance + Permission = Discernment,” which is a helpful concept for parents, but also for anyone worrying about their own relationship to any particular food. The less you have to worry about whether you’re allowed to eat a food, the more you’re able to figure out if you actually want to eat it.

Something else that’s helpful for all of us to remember: Having intense feelings about food often doesn’t have anything to do with a particular food. My 3-year-old’s tantrum yesterday was ostensibly about our lack of Goldfish and I get how that makes her look like a “cracker addict.” But when I opened up her lunchbox, I saw she hadn’t eaten any of the snacks I’d packed for the day. She was just hungry. And tired. And a thousand other emotions entirely unrelated to food that are hard to articulate clearly whether you’re three, or 40.

So no, white flour and sugar are not addictive, and as you think about how to introduce solids to your baby, I would think much less about how any particular food is formulated and much more about the messages your child is receiving about that food.

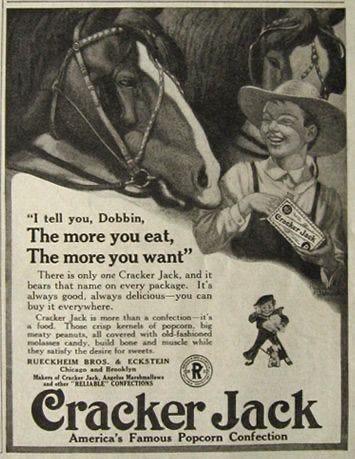

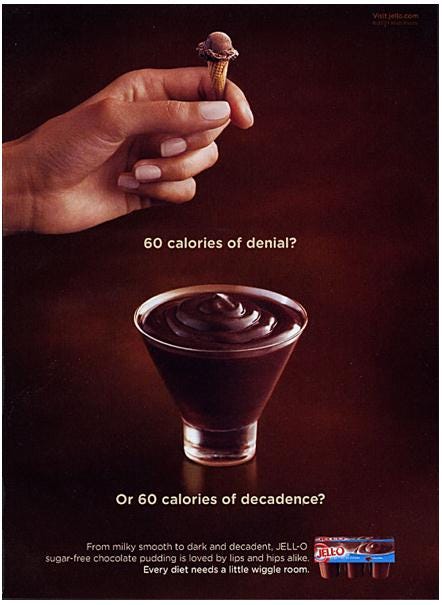

And to that end: I do worry about how processed foods are marketed, because most of them are selling diet culture. Consider that old campaign slogan for Pringles: “Once you pop, you can’t stop!” Or the way Milano Cookie #SaveSomething4U commercials teach us that the only time moms can eat cookies is when they are hiding from their family in a bathroom they should be cleaning. My Twitter followers came up with about a million more examples here if you want to fall down a rabbit hole. (Magnum relaunching their “Seven Deadly Sins” ice cream is maybe my favorite for sheer creepiness? But let’s not leave out Oreo packaging designed to help you hide them from your kids!) The point is that every one of these reinforces the myth that you should crave these foods because you’re not really allowed to have them—because you can’t control yourself around them.

Consider too, how many processed foods are marketed more heavily in low-income Black and brown communities. As I reported in The Eating Instinct:

Shiriki Kumanyika, a research professor at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health and founder of the Council on Black Health, has been tracking the efforts of food marketers for over a decade. Her research shows that mainstream food brands target minority communities with messages they don’t send into white markets. African American and Hispanic kids see twice as many ads for candy and soda as their white peers. Media channels aimed at minority audiences also show a higher percentage of food ads than those aimed at white or mixed audiences, and the foods advertised tend to be less healthy. Certain brands (one study pinpointed 7 Up, Kraft Mayonnaise, and Fuze Iced Tea) advertise only on Spanish-language channels, while others, such as Wendy’s and McDonald’s, devote significant portions of their advertising budgets to Black or Hispanic media. Kumanyika says this isn’t a conspiracy; it’s just how marketing works. Part of the problem is surely that black media outlets sell more space to food advertisers because other kinds of advertisers—airlines, makers of computers and luxury cars—don’t care about reaching a less affluent market. But either way, the result is clear: “Black people see all the ads targeted to the general population and then they also see ads targeted specifically to black people,” says Kumanyika. “It’s double the exposure.”

More on this here and in Kumanyika’s full research bibliography here (Yup, again, CW: Lots of o-words in both).

Reading that back, though, I wonder about my shrugging 2017 acceptance of Kumanyika’s framing that “this is just how marketing works.” Because many of these same foods are the ones most demonized by white-dominated diet culture marketing. “I think about the utility of marketing those foods as something that health-conscious, respectable people shouldn’t be eating. Who benefits from that?” asks Mercedes. “A lot of the discourse that demonizes certain foods over others is a marketing ploy to push some new form of eating, like clean eating, or vegan or organic.”

So yes, this is how food marketing works. But cut the “just.” This is Coca-Cola selling both regular and Diet Coke, and Kraft-Heinz selling both Kraft Mac and Cheese and Back To Nature Mac and Cheese, and also owning Oscar Mayer and Lunchables alongside Smart Ones and Crystal Light. They sell whiteness versus other-ness and restriction versus indulgence because these are our most profitable cultural narratives. You don’t have to call it a conspiracy theory but it is intentional and predatory and clearly causes a lot of harm.

What feels less clear is what we do about this. Both the processed food industry and the diet industry could use more regulation and oversight to stop predatory marketing practices, especially in communities of color and to children. And while we’re at it, it would be nice if we held both to a higher health standard so it wasn’t so easy for companies to lie on labels in about 700 different ways. I’m also fine with holding corporations to more stringent environmental and human rights standards.

But: Deciding that you’re going to cut out a group of foods, even if it’s because they promote diet culture, sounds a lot like… more diet culture. Stripping processed foods from your life requires privilege in the form of time, money and labor. It also doesn’t do much to help anyone besides you. And most eating practices that start as a moral imperative run the risk of ending up as a restrictive diet.

More crucially: None of the problems I’m highlighting here are with the foods themselves. Processed foods are not bad foods and you are not bad for eating them. So maybe the first thing we need to do is stop ending the conversation there.

ALSO

Coming up: On Thursday’s subscriber-only audio post, I’ll be talking with dietitian Christy Harrison of Food Psych and the author of Anti-Diet. We’ll talk about cauliflower rice, how deprivation fuels the restrict-binge cycle, the Michael Pollanization of food discourse, and much more. Subscribe now:

Previously on Burnt Toast:

Re that Twitter thread: any reference to "clean" eating just makes me do a Tasmanian Devil twirl of rage. Panera commercials in particular will send me right over the top.

Every time I read your newsletter I just see constant fire emojis and I want to highlight every other paragraph.