What Instagram Gets Wrong About Feeding Your Kids

Division Of Responsibility was supposed to be the anti-diet way to feed kids. Then the influencers arrived.

First, some housekeeping!

This Thursday, I’m doing a Very Special Episode of the audio newsletter with Amy Palanjian of Yummy Toddler Food. Some of you will know her as my former podcast wife and she last visited Burnt Toast here. We decided to get the band back together to talk about Halloween candy because The Most Sugar-Phobic Time Of The Year is almost upon us! We want you and your kids to eat all the Snickers without feeling weird about it.

And in the spirit of giving out candy—this week’s audio newsletter will go out to everyone! Audio newsletters have historically gone out to paid subscribers only, but I’ve decided to switch that up and make all guest episodes free. It hasn’t been sitting right to be keeping brilliant guests behind a paywall, especially when I’m featuring folks whose voices need to be centered. So I’m thrilled that the support of paying subscribers is now making it possible for me to make even more Burnt Toast content accessible to all.

Paid folks, don’t worry, you still get cool perks! The current list includes commenting privileges, our awesome Friday Threads, and Virginia Q&A episodes, which will continue to drop once or twice a month. If you have a question you’d like me to answer in one of those episodes, you can hit reply and send it over. And you can read more about my decision to add paid subscriptions to the newsletter here.

Last thing! If you decide to subscribe this week, you can take 20% off your subscription by clicking here. This discount gives you all of the paid subscriber perks for just $4 per month or $40 for an annual membership, for the first year. Thank you so much for supporting independent anti-diet journalism!

Did Instagram Ruin the Division of Responsibility?

Evie Ebert’s son, now age 6, has never been much for food. When she introduced him to solids as a baby, he spit most things out. By the time he was a toddler, he had a short list of accepted foods even compared to other picky eaters his age. “This was a big blow to my ego,” says Evie, who is a fellow Substack writer and mom of two in Chestertown, Maryland. “I always thought just by the power of my cool personality that I’d have a kid who loved kale or whatever.”

Evie turned to her mom friends for advice—a community she describes as “very brainy, but not into over-achieving or perfection”—and they all told her: You need Ellyn Satter’s Division Of Responsibility In Feeding. DOR, as it’s more commonly known, guides parents away from pushing bites and nagging kids to eat, while also empowering them not to play short order cook for picky eaters. “I loved that it gave me permission to let myself off the hook in these ways,” says Evie. And lots of the moms who endorsed DOR held up their now-6, 7 or 8-year-olds as proof: “I bought into a lot of testimonials that these kids had all been picky toddlers and were now eating what their parents ate,” Evie says. “That was very intoxicating to me.”

If you’re not familiar with DOR, it’s worth clicking the link above to read about it straight from the source. Ellyn Satter is a dietitian and family therapist who developed the DOR framework more than 30 years ago and has since published many books and case studies supporting it. Her method has long been championed by pediatric dietitians and childhood feeding experts eager to get parents to break with the more punitive “clean your plate” model of child feeding. Within the past 10 years, DOR has moved from a niche technique to mainstream feeding philosophy—and that’s thanks in part to Instagram.

Full disclosure: It’s also, a teeny bit, thanks to me. I wrote about DOR for the New York Times Magazine in 2016 when I told the story of our baby who couldn’t eat. I did a deeper dive in my first book, and wrote about DOR again for the NYT Parenting section in 2019. Amy Palanjian and I also spent many episodes of our former podcast dissecting how to implement DOR, and those conversations have informed Amy’s work as a kid food influencer. And I’ve endorsed it plenty of times right here in this newsletter. As a parent trying to escape diet culture, DOR has so often felt like the answer because it helps us to stop policing our kids’ bodies. I decide what we’re eating. My kids decide how much of that meal they want to eat. No food pushing, no coercing, no portion-controlling. Done.

But I get why, for Evie and many other parents, DOR becomes a kind of diet. Dutifully sticking to her responsibility to decide “what kids eat,” Evie served her son a perpetual variety of vegetables and grain salads, all the while insisting he didn’t have to eat them. Then she watched, quietly panicking, for years, as he... continued to not eat them. “I thought the promise of DOR was that, at some point, your child will be ‘fixed,’” she says. “And so for a long time, I saw his eating as a problem that needed to be fixed.” Earlier this year, Evie wrote about why she broke up with DOR for Romper. It wasn’t easy to admit that this beloved progressive parenting method hadn’t worked for her. Especially online. “There’s this vibe of ‘well if it’s not working, you’re just not doing it right!’” she says.

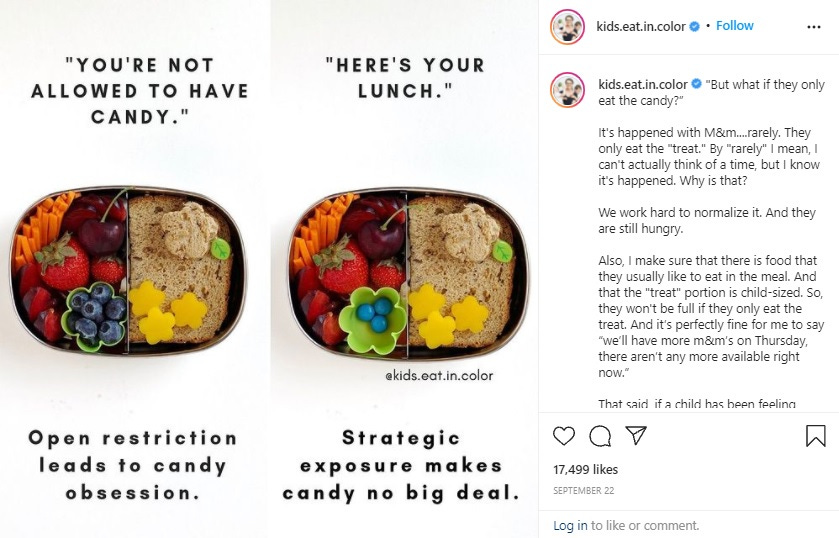

That vibe—which yes, is also what diet brands say when dieters don’t lose weight—comes straight from social media. “I feel the flavor of Satter’s principles in almost every kid food influencer on Instagram,” says Evie. “At least all the mainstream ones who are focused on vaguely crunchy, neurotic white moms.” Accounts like @solidstarts, @kids.eat.in.color and @weelicious are all strongly influenced by the DOR ethos, if not full-on ambassadors for the cause. And something happens when we pair the principle of “parents decide what to serve!” with aspirational rainbows of produce arranged on pristine white backgrounds. DOR is supposed to be the anti-diet way to feed kids. But, on Instagram at least, diet culture has arrived for DOR.