New year, not so new diet trends.

Ah, the first week of January. When my inbox overflows with press releases from weight loss companies, fitness experts and diet gurus, and even sober and reputable media outlets, like the New York Times, propose we all go on crash diets. (This year it's op-ed columnist David Leonhardt telling us to go cold turkey on sugar for 30 days). It always sounds so possible, and even downright sensible, after the weeks of holiday excess. I know at my house, we've had a constantly refilling tray of cookies and a bowl of candy on the kitchen counter for much of the past month, and it was with no small relief that I dumped the last six stale cookies in the trash yesterday, after realizing I wasn't morally obligated to finish them just because they were there.

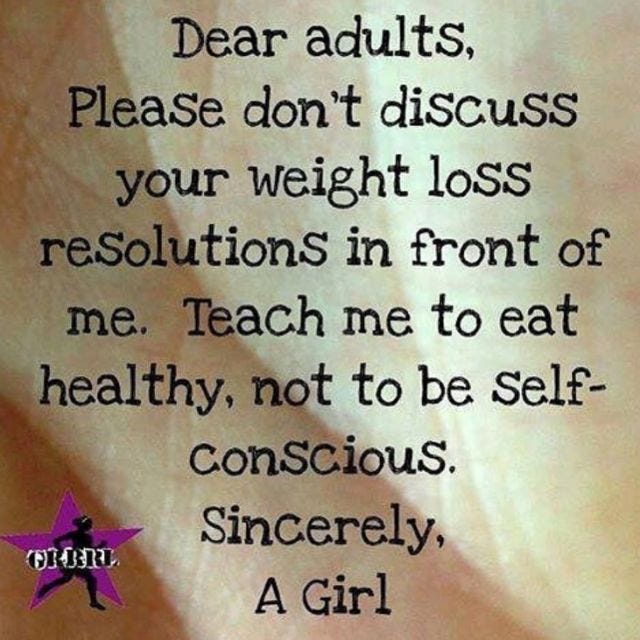

But nor am I morally obligated to now avoid all of the cookies, forever, just because we've started a new year. Yet eat better/lose weight resolutions are always accompanied by an onslaught of shame. It's not enough to say "hey, eating more vegetables sounds interesting to me." You have to project the appropriate sense of disgust and horror at your current eating habits, to feel gross physically and mentally because you ate all that sugar (and cheese and pasta and...). And that means, when we fail — and most of us will fail — that we'll need to feel like failures. And start the cycle over again.

Of course, not everybody processes this much guilt around food. Leonhardt, for example, seems rather easy-breezy about it all, writing, "I missed ice cream, chocolate squares, Chinese restaurants and cocktails. But I also knew that I'd get to enjoy them all again." But he still needles those of us feeling "a little guilty" about our sugar consumption to try his plan. And he does so glibly because the language of remorse and punishment is baked into our thinking about food now, as Amy Palanjian points out on The Kitchn, where she resolves never to use the words "clean eating" to describe her diet. (Which, clearly, is the kind of resolution I can get behind.)

I investigated the science (or lack thereof) behind "detoxing" (otherwise known as crash diets, or anytime you cut out one or more major food groups for a dedicated period of time) for a piece a few years ago. And I was interested to learn that for a certain subset of the population, adopting mildly healthier eating habits truly is easier to do after a period of strict abstinence. As Leonhardt notes, naturally sweet foods like fruit taste better when you've forgotten the hyper-sweet flavor of say, a pint of Ben & Jerry's. After enough of a break, the ice cream may be even become unpalatably sweet when you do return to it, so you eat less. But for many other people, periods of intense restriction only lead to lost weekends (or months) of excess. It fuels a cycle of all-or-nothing eating, where if they can't eat "perfectly," they might as well not even try. (This also happens with exercise, by the way; I know because I did it for years.) We don't know precisely why people react the way they do to these kinds of diet experiments. Perhaps their tastebuds register sweet sensations differently and the ice cream is still just as irresistible 30 days later. Perhaps our cultural obsession with "good" and "bad" foods has seeped deeper into their brains, making it harder to detach their feelings about themselves from their food choices. But I'd suggest that anyone considering a New Year's diet or detox should also spend some time considering what they'll really feel like on the other end — based on their own experiences around food, not the program's glorious promises.

All that being said, I did find the NYT's interactive "How Much Sugar Can You Avoid Today?" menus utterly fascinating. Not because I think you should quit eating granola for breakfast, which offers a nice dose of fiber and other nutrients, alongside its 14 grams of sugar (plus you might just like it!). But because I do think being educated about nutrition is an important part of learning to eat. The question is, how do we teach people about what's in their food without shaming them for eating that food? I'm not entirely sure, but I have a feeling it doesn't involve detoxing.

(Image courtesy of A Mighty Girl.)