No One Needs Your Workout Selfies

At least, not until we can untangle exercise from weight and virtue.

REMINDER: We're planning a special AMA episode of the podcast! If you have questions for me, please submit them via this Google Form to help us stay organized. Everything is fair game!

Spring has finally (mostly) come to the frozen tundra I inhabit in New York’s Hudson Valley. For me, this means the start of serious garden season. But it also means: Spring 5Ks! Iron Mans! Marathons! Tough Mudders! My social media feeds are awash in photos of cheerful people in brightly colored exercise clothes, sweating vigorously in the sunshine.

This is, of course, just the new seasonal twist on the workout content that populates social media every day, all year long. It is now normal to know your old college roommate’s Garmin stats, to see your former co-worker thirst trapping from his weight bench. And to know exactly who, among your acquaintances, bought a pandemic Peloton and how much they love Ally Love. (So much. They all love her so much.)

It’s also normal to follow influencers with huge platforms who have built their entire brand around their workouts, or the body that has resulted from said workouts. Hilaria Baldwin films herself doing squats in her bathroom, while brushing her teeth. Brie Larson lets us know when she can leg-press three times her body weight. In fact, pretty much any mainstream celebrity or influencer in the beauty, fashion or lifestyle spaces is expected to check in with us before, after and during their workouts. We know their stats, we know their recovery smoothie recipe, we know their favorite sports bra. And in the case of dedicated fitness and weight loss influencers, we follow along as they dramatically change their bodies in short periods of time. As I write this, over a million of us are watching one such influencer, Lexi Reed, recover from organ failure caused by a “mystery illness.” To study Reed’s grid now is to see just how fast she went from posting gym selfies and motivational quotes to being in a medically induced coma. And now, the motivational quotes are back, along with discussions of her months on dialysis, fighting kidney failure, and shots of Reed in a hospital bed or a wheelchair, still #weightlossjourney.

Reed has not commented publicly on the cause of her medical struggle, and I won’t speculate about her health, her body, or her relationship with diet and exercise. But to see someone’s very public quest to improve her health through exercise and weight loss culminate in this kind of medical catastrophe does raise a few questions. And not just for Reed. What are any of us really doing when we perform exercise online? And why are we doing it? Because this is not about health.

Look, I have also posted many, many workout selfies in my time: Me in a yoga headstand. Me finishing the swim leg of a triathlon. I’ve posted photos from woods walks with my dog, and from the time I went to a Jessamyn Stanley-taught yoga class in New York City. I think my most recent dedicated workout content was this past February: I InstaStoried a treadmill shot (calories redacted) of the first 15 minutes I managed to walk without pain, about a month after I fell in our icy driveway and sprained my ankle. But just yesterday, I posted a shot of me hiking in Joshua Tree (with a trekking pole to keep said ankle safe).

So before you read what I’m going to say next, I want to be clear that I have been a part of this thing, too. And I get it. It’s complicated. We’re going to talk about it. But: Most of us need to stop posting workout selfies. Or at least, we should sit quietly for a while with why we do it. And name its potential for harm.

Social media algorithms are built for workout content. Instagram and TikTok love to show us bodies, preferably thin (or fat-but-getting-thinner), able, white bodies. These bodies are often caught in mirror selfies, or shot from above, with the camera angled down into cleavage. The algorithm loves a thin, bikini-clad woman jumping off a dock. It loves sweaty visible abs and a sucked-in stomach. It loves workouts shot in time lapse, #grind, and #progressnotperfection (accompanied by an image that approximates perfection). The algorithm will show these posts to many more people, many more times, than they will your post of your houseplants or your cute dog. This is why posting workout selfies, even if you are not an official Influencer, is a sure-fire way to get a load of likes and validation for this thing you’re doing.

And is that so bad? You may think, well I don’t have visible abs, or I’m not an influencer, I’m just a dude who does a lot of triathlons, why can’t I post about my cool hobby? But remember that thin is not a personal preference. We live in a culture that equates exercise with weight loss and athleticism with thinness. We are also taught to place moral value on exercise; to revere both the hard work and the pleasure of physical activity as somehow better than any other kind of work or pleasure. We celebrate bodies that excel at exercise even though that means we’re also placing far less value on disabled bodies, fat bodies, and any other bodies that don’t excel at exercise.

Some workout content clearly and deliberately leans into all of this: Lexi Reed’s weight loss journey, of course. See also, posting your calories burned or pounds dropped. But we’re leaning in as well anytime we engage in the vernacular of weight loss and body shaming—“cheat day!” “gotta earn those margs!”—whether or not we’ve stated an explicit weight loss goal. These tropes all perpetuate ableism and anti-fat bias because they demonstrate your desire to not be fat or disabled.

But I’m not sure it’s all that much better even if we drop all the stats and weight talk. If we have thin privilege (and remember that we don’t have to be very thin to benefit from thin privilege), our workout content is reinforcing the importance of striving for the thin ideal, even if our body doesn’t perfectly adhere to it and even if we never talk about calories or weight loss. And, if we have able-bodied privilege, our workout content is reinforcing ableism. Neither of these things are entirely our fault. This is the cultural narrative we all participate in. We’re constantly looking at thin, able bodies because that’s what every form of media serves us unless we deliberately and consistently choose to see something different. And when we post workout selfies, we add to that litany of “good” bodies. We aren’t challenging the norm; we’re asserting our right to be counted within the norm. We’re making it known that we have, in fact, earned those margs.

One common defense of workout selfies is that they’re somehow okay as long as your intentions are “pure.” As long as you aren’t deliberately trying to make anyone feel bad about their bodies, because you aren’t even thinking about other people’s bodies, after all! You’re posting because you’re focused on your own body, and isn’t that your own business? The photo is just proof that you did the thing. It’s motivation. It’s accountability. It’s empowerment. And hey, if anyone is offended, it’s free to unfollow.

All of that is true. But it ignores how much the post itself is a performance. You’re requiring accountability to others. You’re finding motivation by sharing your photos with others. In posting, you are demanding a relationship with, and a response from, your audience. And that means you have a responsibility to that audience as well.

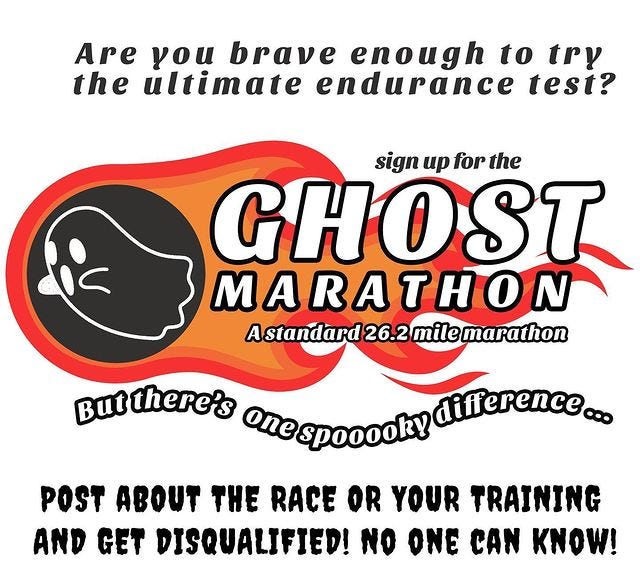

Okay, so what about workout content that isn’t selfies? These break down into a few categories. The first, which we can draw bright lines around, are the Strava, Garmin, Peloton, etc-manufactured posts that share your stats. It helps when people block out calorie counts, but other numbers (especially distances or times) also invite the audience to engage in unhelpful comparisons. I don’t discount the fact that many people sharing stats like this are working towards goals that are giving them tremendous personal satisfaction. But is the documentation of that goal worth the potential cost to followers who will find these posts stigmatizing? Could we instead share this content with a smaller group of fellow exercise enthusiasts who have opted into the conversation? If not: Why do you want us to know how far or how hard? How do you hope we’ll interpret that? Would you still do the workout if you couldn’t tell us about it?

The next non-selfie category would be “experience” workout content: Posting a photo from a beautiful hike, or a swim in a lake. When I’ve discussed workout selfies before on here, and on Instagram, a significant portion of you say that you feel differently about these, and I agree because we’ve stripped away the stats, and maybe the bodies too. Maybe it’s just a photo of a happy dog on a mountain, or your feet in running shoes. We haven’t dispensed with the performance though. And it’s worth noting: These photos still require privilege. “Honestly, seeing content about hiking/skiing is more prickly for me than seeing exercise content, perhaps because my issues are more tied up in class/money/time, and my brain goes immediately to the past or current barriers between me and those kinds of activities,” one commenter noted. They also involve able-bodied privilege. Anna Sweeney, a social justice-oriented dietitian who lives with MS, asks folks to send her #inaccessibleviews on Instagram, as a way of sharing beautiful places with folks who can’t physically get there. (Anna and I also discussed ableism and diet culture here.) It feels like an important way to start that conversation, but clearly, we’re not doing enough to make such places more accessible and inclusive.

The final category of workout content that deserves its own discussion is fat or otherwise marginalized people working out not for weight loss reasons. I want this one to be unequivocally good: Body diversity! Representation! Joyful movement! And I think there is so much good to be found in the work of Jessamyn Stanley, Meg Boggs, Unlikely Hikers, Ilya Parker, Ragen Chastain, Shannon Kaneshige, and more. They have helped me personally re-conceive of fitness as something I can do for myself, and even for fun, without metrics or body size goals. They also share knowledge and build community for folks who don’t feel welcome or safe in traditional fitness spaces. (And to that end, I’ll also shout out the work of inclusive fitness influencers in smaller bodies who work very hard at this: Lauren Leavel, Chrissy King, Jamie of Fitragamuffin, Casey Johnston.)

And yet, even here, there is a tension. When, as fat people, are we pursuing movement on our own terms, and when are we performing it, as a Good Fatty who needs to let everyone know it’s okay that I’m fat because at least I’m healthy? “I’m someone who loves sports and who does ridiculous fitness-y things,” Ragen Chastain told me when she came on the podcast. “But just to be super clear: Health and fitness, by any definition, is not an obligation, not a barometer of worthiness, and not entirely within our control. I always want to be clear that completing a marathon or having a Netflix marathon are morally equivalent activities.”

Fat people sharing joyful workout content helps us fight for space in a world that doesn’t want fat people to experience joy in our bodies. See this Sofie Hagen post about climbing a mountain while fat (and out of breath). And, as Ragen wrote recently, it’s not a failing (at any weight) to decide you just do not find movement joyful:

I can’t tell you the number of times someone’s face completely lights up when I say “Look, it’s ok to pick something you hate the least, and do the bare minimum you need to do for the benefit you want to get.” For many people there is liberation in the idea of fitness as something like dishes or laundry – it’s something they do to support themselves, but not necessarily something they love.

What Ragen is articulating here is what we see in Roxane Gay’s workout content, which is almost always just a straightforward, unstyled shot in Stories of her unsmiling, sweaty face noting “30 minutes with trainer” and nothing further. (She also never saves these images, so I can’t link them for you.) There is no journey, there is no earning of anything, no #progress. It’s just a thing she’s doing to support herself and that’s all it ever needs to be.

I’m not arguing that this is all fitness content should be. But I am saying: We are very far off from fitness content ever feeling as benign as cute dog content. To get there, we need to untangle exercise from both weight and morality. We need to change our understanding of “health” to encompass all the ways health is determined (or not) by factors outside our control. We need to stop assuming disinterest equals failure. And we can’t make this change on social media alone; we have to dismantle and reform larger societal systems like healthcare and education too. So while we’re working on all of that, maybe we could hear less about your leg day?

Dear Sugar: I love this piece by Emiko Davies on why we love sugar, why we should love sugar and (louder for the people in the back) why sugar highs are not a thing. (She quotes my work and last week’s podcast, but I’d be linking it either way because everything Emiko writes is so good!)

The Noom Paradox: Because we can’t go over this one too often, Constance Grady has a great piece on Vox about yes-it’s-a-diet Noom trying to hang onto its moment.

This is a tough one for me. I was an unathletic kid and felt totally discouraged by the adults around me from pursuing sports or fitness because I “wasn’t good at it.” It wasn’t until I was an adult that I realized I could actually learn and improve at various exercise activities on my own terms and for my own benefit, even if I was never going to be “the best” at anything athletic. I do credit social media a lot for helping me find find fun and safe ways to exercise and helping me change my thoughts around food and fitness (Casey Johnston is a favorite follow of mine!), and I love seeing people find joy and fulfillment in exercise. So many hobbies have kind of weird virtue stuff wrapped up in them — side hustles, reading challenges, that kind of thing — and while I do think exercise has more baggage attached, I think it’s something we should really actively be trying to separate from food and thinness on social media, rather than erasing fitness content from social media until we can make the necessary cultural changes for it to be okay again. I agree with one of the other posters here that the issue is more with the algorithms and the platforms than with individual users.

Like you have been reading my mind. A friend/former colleague on Instagram started posting pictures of her epic walks. Just feet or scenery. But I started waiting..knowing it would come. Because she had lost a lot of weight several years ago, then gained a lot back with two kids, and I just knew this was going to be the start of weight loss posts. After several months it finally came a week or so ago. It was staggering how much it hurt. All the “congrats” with the body picture and weight loss number. And I was like: I genuinely have to unfollow this. And of course the chorus in my mind singing: see, if you just tried harder…