The Problem with Portion Control Science

In the first five years of my career, I wrote about weight loss pretty often. My work was almost entirely in women's magazines at the time, and fledgling freelance writers do not get to be precious about their assignments. Internally, I wrestled a lot with where to draw the line when it came to writing diet stories. I didn't write them for teen magazines. And I've never advised anyone to live on grapefruit for a week, or do anything else blatantly dangerous. Instead, I pitched stories that required a ton of research about blood glucose regulation or metabolism. I tried to focus on nutrition instead of weight loss — even though, unfortunately, nutrition is almost always researched and written about in terms of weight, so almost every nutrition story ends up feeling like a diet story somewhere along the way. But I thought that if science could tell us the definitive way to lose weight without feeling miserable and deprived, then that would be worth sharing with the world. It wasn't until I did this for a few years that I realized scientists have yet to discover such a unicorn.

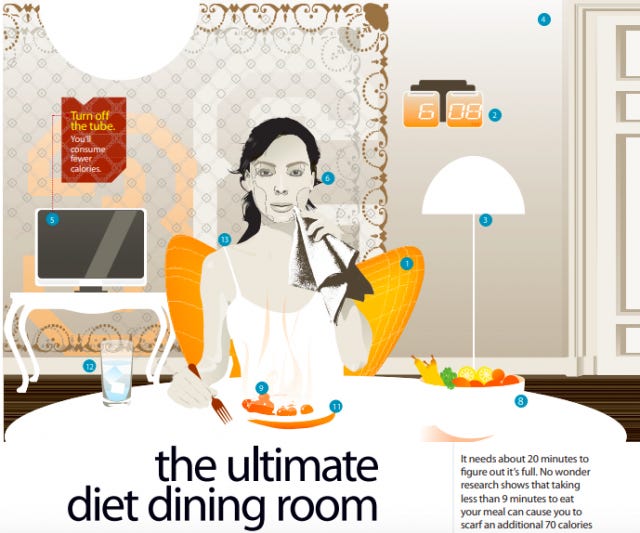

During this time, I wrote a lot of stories spotlighting the research of Brian Wansink, director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. (Here's one, from the May 2007 issue of Women's Health.) Dr. Wansink was beloved by magazine editors and writers like me because his studies were fun to write about. He did experiments where he secretly refilled people's soup bowls or swapped the size of their wine glass to show how we mindlessly consume extra calories. And Wansink wasn't just a women's magazine darling; he was an Ivy League professor and best-selling author, appointed by the Obama White House to lead the USDA committee on Dietary Guidelines from 2007 to 2009. His research and thinking on nutrition has directly informed how school lunch menus are designed, as well how we now generally view things like portion sizes and restaurant menus. Wansink's work resonated with me because he didn't shame or blame the eater — his goal was to show just how susceptible we are to the food environment around us. He worked with healthy food advocates and food marketers, so there was a kind of amorality to his science that I appreciated. He wasn't taking sides, just showing how powerful the food environment can be. And it made it seem like healthy eating habits were just a matter of catching on to a few tricks that would fool your body into being satisfied with smaller portions: Use smaller plates, turn off the TV, play the right music and weight loss would be easy-peasy.

Alas. Last month, BuzzFeed News published an exposé of Wansink's research. Science reporter Stephanie M. Lee dug through eight years of emails to show how Wansink urged his grad students to massage data to support media-friendly conclusions and push low quality research out into less prestigious journals with lower standards in order to keep up his frenzied publication schedule. Other critics have pulled together the Wansink Dossier, a long list of errors and inconsistencies found in dozens of studies. So far, he's had five papers retracted and 14 corrected.

Losing weight, it turns out, is not as simple as swapping out your dishware. And getting kids to eat fruits and vegetables takes more than putting Elmo stickers on their apples. But the Wansink scandal isn't just a story of one scientist padding research. It's also about what the media demands of weight loss scientists: Quick, easy solutions that lend themselves to headlines, graphics and memes. It's what everyone wants for weight loss, because we want it to work and not to be very much work, at the same time. Wansink figured out how to deliver the stories we needed, and we loved him for it. And all that media coverage raised his stock — to the tune of the $20 million in taxpayer funds that the USDA spent on his school lunch initiative — but also expectations about what he would discover next. If all of the allegations are true, then Wansink behaved unethically, to be sure. But he did so at least in part because this is what diet culture is doing to nutrition science.

I still appreciate that Wansink's research focused on positive solutions instead of shame-based strategies. We need more of that — backed up by actual science, of course. But even more, we need to get away from the idea that weight can and should be manipulated through quick fixes with food. At the core of Wansink's research is an understanding that our hunger and fullness cues are easily manipulated and disrupted by the world around us. And that fundamental idea isn't in dispute here — plenty of other researchers have shown it as well. It's when we try to protect those cues through more external tweaks and rules that everything starts to break down. I remember once trying to implement a Wansink trick, and served dinner on salad plates: I didn't feel full faster. Instead, I spilled sauce because the small plate couldn't contain everything, and felt guilty about wanting seconds when my appetite didn't match up to my expectations of what the right portion should be. We can't trick ourselves into a healthy relationship with food. But even if Wansink stops publishing, the diet industry will continue to persuade us we should try.

**

Book Report.

THE EATING INSTINCT is stil justl a computer file, being combed over as I type this by a copy editor and fact-checker. But it has a cover and an Amazon preorder link! I'll have more info about both in upcoming newsletters, but in the meantime, feel free to click and share with wild abandon.

**

Friends tell friends when they enjoy newsletters.

Tweet this: "We can't trick ourselves into a healthy relationship with food." -@v_solesmith on the #BrianWansink scandal, more at https://tinyletter.com/virginiasolesmith.

And, as always, thank you for forwarding, sharing and subscribing.