Two weeks ago, the FDA announced that it’s pondering new rules about who can use the word “healthy” on food labels. On Thursday, I hopped on NPR’s All Things Considered to chat about what this means. But of course we couldn’t cover all of the nuances in a four minute interview, so I decided to do a deeper dive for all of you.

Here’s how things currently stand: When a manufacturer wants to put the word “healthy” on a food label, it has to make sure that food adheres to a set of nutrition criteria from 1994. Look, I spent most of 1994 wearing chokers and a lot of plaid flannel in a quest to look like Angela Chase. So no judgment for where we all were then. But it was not a great year for nutritional science and it’s a little absurd that the government is still defining “healthy” by those low-fat, cholesterol-phobic, lite yogurt metrics of yore. The current FDA definition of “healthy” excludes avocados, nuts and seeds, salmon and water, reports The New York Times.

The FDA’s new version of healthy would apply automatically to all fruits and vegetables (#justiceforavocados). It also requires all food products to contain a certain amount of food from at least one food group (fruits, vegetables, dairy, grains and protein). A “healthy” food also cannot exceed new limits on added sugars, sodium and saturated fat. Look, we can get very in the weeds here. The FDA is clearly happy to be reclaiming salmon and eggs as healthy, two decades or so after the rest of us went there. But they’re putting a ton of guardrails around these foods. So if you buy a frozen salmon dinner that comes with a sauce that exceeds the added sugar or sodium limit, the FDA would say that’s unhealthy. Does adding extra sugar negate the health benefits of the salmon? I’d argue no, because salmon without a delicious sauce is salmon I don’t want to eat. Dipping carrots in ranch dressing (or ketchup or maple syrup!) doesn’t make carrots unhealthy. It makes carrots a food more kids are willing to try. Getting worked up about how much ranch dressing is too much is straight out of my old women’s magazines diet story playbook. This is de facto calorie counting and it infiltrates your experience of eating the carrots or the salmon, making you judge yourself if you don’t feel satisfied by the prescribed amount.

So right off the bat, we can see that figuring out how to define “healthy” and decide which foods get the “healthy” label is a fraught endeavor. There may be some benefit to this happening on a population level, and I’ll get to that in a minute. But on an individual level, obsessing over “healthy” and “unhealthy” foods (otherwise known as “good” and “bad” foods, “whole foods” and “junk,” or insert your own dichotomy here) is unhelpful and often dangerous. Restriction breeds fixation.

And getting caught up in how much sugar and “yes, all avocados” ignores a larger truth: We don’t need healthy labels on foods. We need a country that treats health as a right, not a commodity or a privilege. It doesn’t matter whether this definition of “healthy food” is a better reflection of current nutritional science than the previous definition. It’s still the wrong definition when we’re talking about “healthy food” in a country where 28.8 million Americans will develop an eating disorder in their lifetime, and 12.5 percent of kids live in households that struggle to get enough to eat on a daily basis.

Every media story I’ve seen about the new “healthy” has quoted the FDA’s research that 80 percent of people living in the United States aren’t getting enough vegetables, fruit and dairy in their diet. But nobody asks whether this is the problem we need to solve, or a symptom of other issues. Even if we decided we could fix the American health crisis by getting everyone to eat more produce, putting labels on food is unlikely to achieve that—just as putting calorie counts on menus and food packages has not resulted1 in people eating fewer calories. (But sure has triggered menu-related panic attacks for plenty of dieters and folks with eating disorders!) The vast majority of consumers already know which foods contain vegetables, fruit and dairy. They aren’t eating those foods for a whole variety of unrelated factors:

“Healthy” foods are more expensive.

They may not fit into a family’s food culture (I cannot wait for the research on how this new “healthy” label gets applied along race and class lines in supermarkets).

It’s developmentally normal for kids to dislike most vegetables.

Eating these foods may require more from-scratch cooking and that’s not something every family has the time, resources, or interest to do.

People (understandably!) don’t tend to prioritize their produce consumption when they’re stressed, struggling with mental health issues, working long hours, continuing to survive a global pandemic.Etc. Etc. Etc.

It’s very possible that our consumption of fruits and vegetables correlates to how we’re doing health-wise, and on a larger societal level. But that doesn’t mean it is anyone’s most urgent problem to solve.

The FDA defines “healthy” in terms of fruit and vegetables because fruit and vegetable consumption is a metric they can measure.2 And because “eat more fruits and vegetables” is a coded way to say “lose weight,” and the FDA, along with most of the organizations and stakeholders who attended the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health continue to equate health with thinness. But this definition is not evidence-based or health-promoting. We live in a country where so many families struggle to access enough food to eat; where so many people struggle to access affordable and non-stigmatizing healthcare; where so many of people struggle with disordered relationships with food and our bodies. To solve those problems, our definition of “healthy” has to become far broader than “what are people eating” and “does this make them thin.”

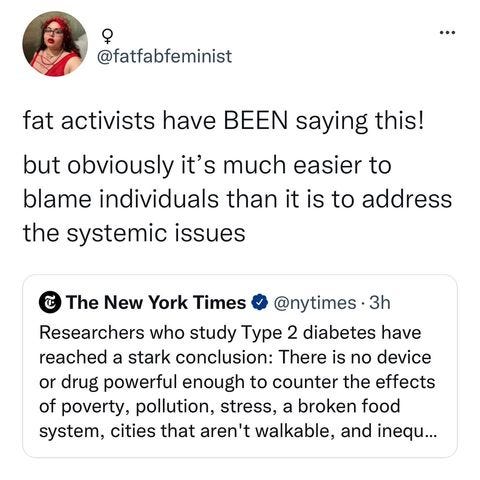

Because, look: If you don’t get enough to eat in a day, fruits and vegetables won’t fill you up and the McDonald’s dollar menu is the healthier and more affordable option. If you are struggling with a restriction-based eating disorder, eating the Oreos and working through your fear that they are a “bad” food is the healthier option. If you are fat (or otherwise marginalized), finding a doctor who will see you as a person and seek evidence-based treatments for your health issues has a bigger impact on your long-term health than how many fruits and vegetables you eat. (Raise your hand if you’re a fat person who already eats the fucking fruits and vegetables and still gets that suggestion from every doctor you see. And props to @fatfabfeminist for calling this out so clearly last week.)

NPR’s Juana Summers asked me what I wish the FDA would do instead of redefining their “healthy” label. And I want to be clear that I don’t actually object to the FDA setting nutritional standards for food manufacturers, especially for manufacturers who market foods to kids. We should have a nutritional floor that everybody has to meet in order to call something food and put it on a store shelf. The nutrition scientists can fight out the details, but I’m willing to say that bar should be higher than “does not contain rat poison.”

The real problem lies in using nutrition standards as marketing terms — because that makes “healthy” a personal responsibility problem. When food brands can market “health,” they offload the accountability for making healthy choices onto consumers, whether or not they have the resources to do so. And they’re able to manipulate our culturally conditioned anxieties about health to sell us foods (and so many other things) we may not want or need. They can also play on these anxieties to sell us “unhealthy” foods —think how many ads for chocolate talk about it like it’s heroin or a wild one night stand—all of which further reinforces our belief that health is a virtue and we’re failing if we’re eating the wrong things (or feeding them to our kids.)

There is an important parallel to be drawn here in the conversation started by this article (and @fatfabfeminist’s post above) where researchers behind a comprehensive national report on diabetes explain that actually, drugs aren’t enough when we refuse, as a nation, to address social determinants of health. And yes, it gets murky. That NYT piece contains many unexamined references to the benefits of weight loss. And those same diabetes experts advocating for cheaper fruits and vegetables and paid maternity leave are also pushing for a new label for added sugar on beverages. Public health has to stop throwing spaghetti at the wall in this way and start separating out which interventions actually address the social inequities that drive health—and which interventions only spread stigma and shame. A good starting point: If your intervention assumes that people are unhealthy because we just “don’t know any better,” or requires us to make feeding our families and ourselves more complicated, we don’t need it. If you’re dismantling stigma, making health more affordable, or even just making it easier for people to eat in ways that are both nourishing and joyful—we’re listening.

O-words and stigmatizing language in that link.

Just noting that yes, they also often include dairy on this list and that’s interesting to me. Nutrition advocates like Marion Nestle love to talk about how Americans eat too much cheese. But the dairy lobby is very powerful. To be clear, I abstain from considering foods “unhealthy” and love cheese. But it does further call the integrity of the “healthy” label into question if the FDA is responding to industry pressure in how they set these criteria.

Gotta love that public health nutrition urge to 'make food more affordable' rather than 'make less people poor'. Really shows what the priorities are, which, in my mind are more about finding justification to keep themselves relevant when they are in fact, largely redundant. They are considering FOP 'healthy' labelling here too; it all just one massive red herring to distract from legitimate health equity, which does not lie in a piece of fucking salmon.

Thanks for mentioning that there needs to be a nutritional floor for food manufacturers. As a public health dietitian, I think this is often the part that gets left out of the conversation, and instead the focus is on how X decision affects a fairly privileged, food-literate segment of the population, rather than the population as a whole. I agree that changes like this trickle down into food marketing in a way that is stigmatizing and shaming to a lot of people -- but they are also used to improve the "floor" for regulations around free snacks for food-insecure children in afterschool programs, for example. Food manufacturers will cut every corner they are allowed to, in order to save money. That is especially true for food products that are not public-facing, such as those that are sold to schools. If the regulation is for "majority of the grains must be whole grains," then every single product will be 51% whole grains and no more. (I went to a school food commodity product tasting -- side note: fascinating! -- and this was absolutely the case.) There is no incentive to them to do anything more than is required, and a lot of incentive to cut corners wherever they can legally do so. The guardrails need to be there to keep them in check, even if it feels arbitrary to create a cutoff point for "healthy."