Who Gets to Blend In, Who Gets to Break The Rules?

And how do we talk about our outfits without talking sh*t about our bodies.

I may never love an outfit as much as I loved how I dressed in fifth grade. It was the first year we needed to change for gym, and in a sea of Adidas Sambas, I wore gold L.A. Gear sneakers. They are on Poshmark right now and I may have to stop writing to go purchase. It was also the year—shout out to 1991— that I started a Blossom-inspired hat collection. I wore a different hat every day, even though the school secretary made enforcing the dress code’s “no hat” rule her raison d’etre. On my way to the bus or the cafeteria, the secretary would swoop in from behind and grab the sunflower bucket hat off my head and run back to her office with it, laughing. I would collect it from her at the end of the day and promise not to wear it again. The fact that I continued to wear (and lose) hats for the rest of the school year was my greatest personal rebellion—which says a lot about how much of my life I have spent being a good girl.

I stopped wearing the hats, the gold sneakers, the layers of homemade Sculpey jewelry, and the giant purple glasses because of other kids. Somewhere between 6th and 8th grade, each of these items became mildly mortifying. I grew up in suburban Connecticut, where everyone wore L.L.Bean backpacks, Umbro soccer shorts whether you played soccer or not (I did not), the aforementioned Adidas, and a lot of Gap and J. Crew. My middle school aesthetic fell somewhere between Punky Brewster and Rayanne Graff, if they were also very into rainforest vibes, and that was hard for my peers to interpret. By 9th grade, I, too, had an L.L. Bean backpack and contact lenses.

Every creative kid goes through some process of deciding how much they want to stick out and how much they need to blend in, in order to survive their tween and teenage years. What once felt special, personal, and unique suddenly becomes “attention seeking,” which, we learn early, is one of the worst qualities a girl can have. So I tried to blend in, more and more, to take up as little visual space as possible. I bought overalls only after all of my close friends were also wearing overalls. I wanted a red pea coat, then regretted getting a cheap catalog brand instead of the J. Crew one that other girls had. It was red in entirely the wrong way, though I still can’t articulate what details made it feel so wrong. When I moved to New York City for college, I discovered the safety of wearing black and buying the right jeans.

As I got older, had kids, and my body changed, fashion became a perpetual problem to wrestle with. Blending in is harder when clothes don’t fit your body the way you’ve been told they should. Fashion as a joyful mode of personal expression can feel entirely out of reach.

I’ve been thinking about this now as I watch my own kids engage with clothes. They are still in this pure place of not even considering how they look to other people. It’s a stage I can only vaguely remember and maybe never totally occupied. They would willingly go to school with tangled hair if we let them skip brushing. My older daughter refuses to wear jeans or ankle socks or ankle boots or really, any clothing that doesn’t have an animal on it. Even then, it has to be an animal she loves and knows many facts about. My younger daughter layers homemade necklaces over various dress-up bin elements (a ladybug tutu, an astronaut helmet) over sweatpants or pajamas. Neither one will sacrifice comfort for style, as I learned to do when I was not much older than they are, and continued to do right up until I left my last magazine job and had to messenger home boxes of shoes I kept in the office because I couldn’t walk more than a block in them outside.

This place of loving clothes on your own terms feels so worth preserving for them, and for all our kids. And yet, it is inevitably fleeting. That my own kids are still at that stage at ages 8 and 4 speaks to their privilege, because for their peers in more marginalized bodies, this freedom is already gone. Linda Gerhardt, who runs the Instagram @littlewingedpotatoes, posted recently about the adultification she experienced as a fat child, and also posted in her Stories how that showed up for her in terms of clothes:

“I ended up willingly surrendering any sense of femininity. I cut my hair short, wore torn up jeans and an army jacket I got at Goodwill all the time. I tried to embrace the parts of me that weren’t feminine so I could craft a new persona for myself, one that would communicate, ‘I know I’m not allowed to try to be a woman. I know that is not available to me. I am doing my best to say I’m sorry for what I look like, and I hope I can just blend into the background.”

The adults in Linda’s life told her not to wear short skirts, party dresses, or the other girl-coded clothes she liked best as a kid, perhaps in part because they were trying to protect her from being inappropriately sexualized. “I guess a leotard or bike shorts look obscene on a fat 8-year-old with boobs, but doesn’t register on a skinny girl,” she says. “But in protecting me from that sexualization, they were also sexualizing me. My body triggered some sort of shame impulse that led them to shame me with comments like ‘how about you wear a shirt over your bathing suit.’” This same process plays out with girls of color at any body size, especially Black girls, who, research shows, are adultified and sexualized much earlier than their white peers.

Thin white children get to stay children for longer and get to enjoy clothes for longer, because their bodies conform to cultural expectations. As a white, cisgender, upper middle class, and (at the time) thin kid, I conformed in basically all the ways that suburban Connecticut demanded. That made it easier for me to occasionally stand out, albeit in socially-sanctioned ways, with the odd dress from the Delia’s catalog, or by wearing sequined Doc Marten’s (that I begged and begged for and then they fell apart after two wearings) with my French-rolled Gap jeans. Being willing to stand out more, when your body already stands out too much for the wrong reasons, requires a different kind of courage, as well as access to fashion.

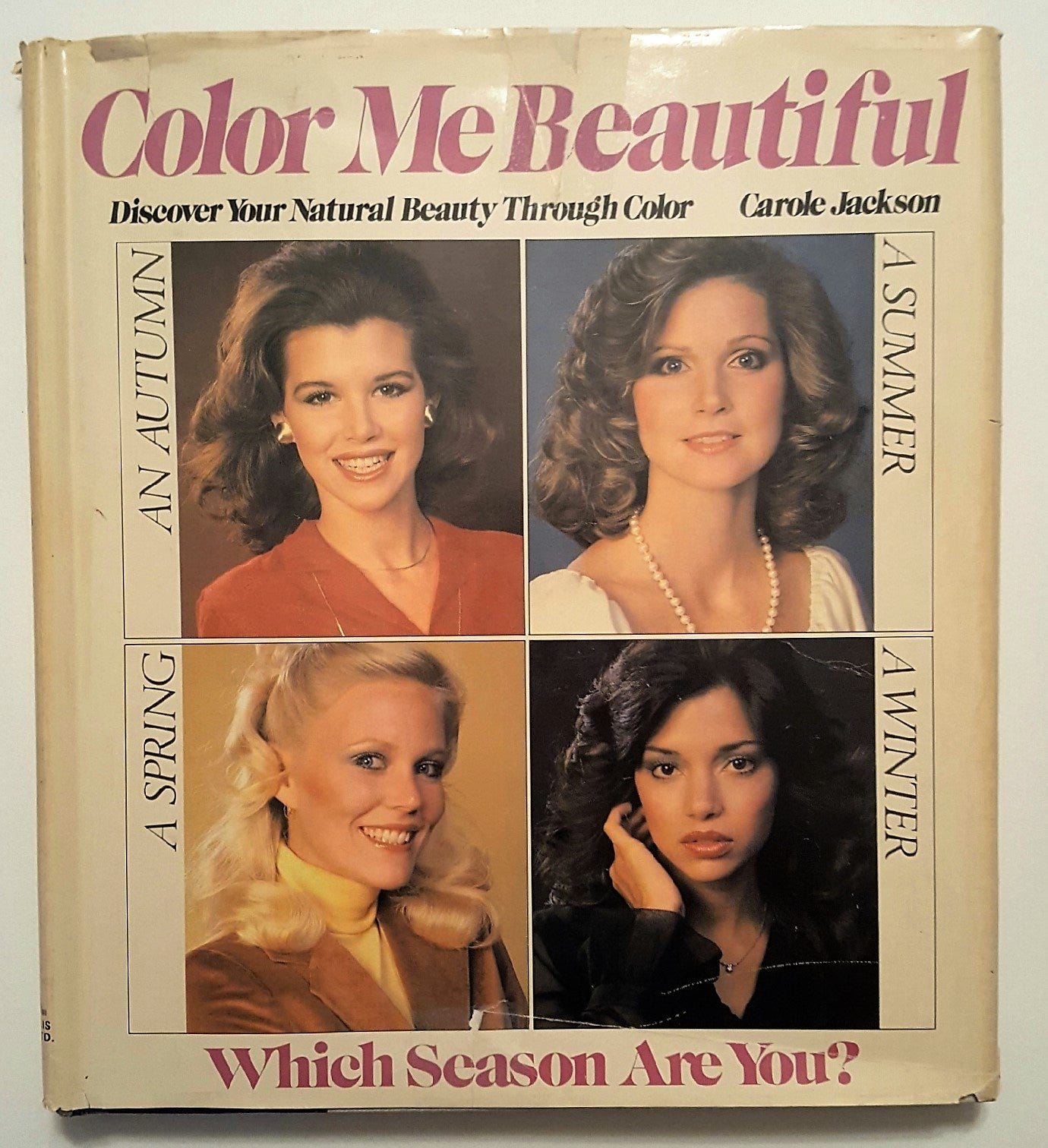

So instead, we try very hard to follow the rules. In 8th grade, I became obsessed with the Color Me Beautiful book/empire, which preached that determining your “season” could enhance your natural beauty and make dressing effortless. The color of our eyes, hair, and skin tones could be sorted into one of four seasons. Neither this book nor the current online Color Quiz, acknowledges the diversity of non-white skin tones; everyone “olive” toned or darker is automatically a Winter. But for the spectrum of white girls, the idea was to diagnose your season and then use its corresponding color palette to shop for clothes and makeup. As a “summer,” I was directed towards a sea of periwinkles and mauves—less Rayanne Graff, more Golden Girls. But the book made finding your season sound like such a game-changer. It promised to make shopping and dressing easy by knowing exactly which colors you could and could not wear. I even owned a little folder of color swatches to shop with. (Also! Apparently this trend is not dead, or so says the Washington Post. But don’t worry, it’s still wildly problematic on race and now has MLM intersections! So that’s fun.)

Looking back, I’m depressed that by 8th grade I was already so far from my joyful relationship with clothing that I needed a literal guidebook to take shopping with me to make the process less fraught. I layered in other rules, gleaned from fashion magazines and the girls at school who seemed to know, always, effortlessly, when the tide had turned from French rolled jeans to bootcut; from Adidas sneakers to ankle boots. I learned how to dress for my “apple” shape and to avoid round necklines, drop waists, and horizontal stripes. That last one comes up over and over whenever I ask other people what fashion rules made them hate fashion. Other common answers, gleaned from Friday’s thread and Instagram: “That form-fitting clothes are for flat tummies only,” “short skirts are for skinny legs only,” “that skinny jeans make me look like an upside down triangle,” “that I need a fucking cardigan over bare upper arms,” and another Color Me Beautiful shout out: “A 9th grade teacher said I should only wear ‘winter’ colors. Avoided all others for years. So boring!”

The irony, of course, is that the game is rigged. You can follow every rule and your body will still take up the same amount of space. The rules are about finding clothes that are “flattering,” which is code for “slimming,” but no amount of flattering is going to turn a size 26 or 16 into a size 6 or 2. And these messages are so, so hard to extricate from fashion. “The entire business model of many stylists and fashion brands is to point out perceived flaws on people’s bodies and then promise they know the answer to 'concealing' those 'flaws,'” says Dacy Gillespie, a personal stylist and creator of @mindfulcloset who is my guest on this Thursday’s audio newsletter. “We are in this business to help women feel better about themselves, but this flaws-based approach only reinforces a very narrow definition of beauty.” And perpetuates the message that only certain bodies deserve to be visible, to seek attention, to take up space.

So what do we do instead? Breaking a rule or claiming a trend you’ve been told doesn’t “work” for your body is a good place to start. I’ve been working with Dacy* over the past few months and you’ll hear more in Thursday’s episode about the various rules and expectations she has helped me to release. You can see some of what I’ve been wearing since doing this work here. It is not quite Punky Brewster, which may be because it’s 2021 not 1991 and I am now a grown-up, or because I’m still working through my taking-up-space fears, or maybe both. (Rayanne Graff is now a countess? We all evolve, I guess.) But there is so much more color and pattern than I let myself wear for many years. Purple glasses are back, along with many other colors. And green clogs are my new Blossom hat?

As for our kids: The more we can encourage their joy in dressing as something they do first and foremost for themselves, the better. Of course, not every kid will enjoy clothes and this is not a passion you need to foster if it’s not their thing. But I think the tension often arrives when clothing is our thing; when we want them to wear a certain outfit for the first day of school, or family photos, or to see Grandma; when we want to revel in all the toddler fashion moments, perhaps in part because these are moments we’ve been denied or are denying ourselves. We had a few years where we started most major holidays with a tantrum because I was insisting on a certain Thanksgiving or Christmas dress and my older daughter wanted none of it. I put her in toddler-sized, red, flowered clog boots (Why did Target not just make them in my size?) until the daycare teachers kindly pointed out that she couldn’t actually run in those and maybe being able to play with other kids was more important than her lewk. I’ve realized there is so much more joy to be found in letting kids direct their own process of getting dressed, in letting them control what goes on their bodies just like I want them to control what goes into their bodies. We want them to know that they—and only they—own their bodies.

In a recent Friday Thread, I loved what Laura L had to say about enjoying clothes with her 11-year-old: “Today my daughter came downstairs in shredded denim shorts, a striped polo, newsboy cap and combat boots, and said, ‘Mom, I think this is my best outfit ever,” she wrote. “I agreed and she asked me why it was her best outfit ever. I emphasized that it was because she had taken four random pieces from her closet and made a look. Nothing about her body. No use of ‘flattering.’ This is really basic, but I’m undoing decades of bad scripts. It’s a daily challenge to talk about our outfits without talking about our bodies. But we’re doing it.”

It’s going to get more complicated. We all know six-year-olds who already know how to find their angles when they pose for photos. The world invades and the lines between dressing for yourself and dressing for the world get blurry. But we can strive to be their escape from that noise; the refuge, where they can, always, take up all the space they need.

*My work with Dacy was not comped or sponsored. It’s something I have the privilege to be able to pay for and I understand hiring a stylist is not within everyone’s ability or even interest. If you’re interested, check out Dacy’s Instagram where there is abundant and amazing free content, as well as group programs and one-on-one coaching.

What’s for dinner: I did an interview with Radio New Zealand about the tyranny of meal planning.

When You Don't Give a F*ck About Their Diet: If you’re wondering how to talk to people about health at every size and/or intuitive eating, this Q&A is a great place to start.

All of this and I’ll also add the expression through hair and makeup into this category. I’m 37 and part of me wants to stop wearing makeup entirely because I feel like as a size 16 woman I have to be super put-together looking (hair and makeup, ‘flattering’ clothes) to show that I’m “making an effort.” I’m so tired of only feeling beautiful or worthy if I’m done up. And this goes back to the seventh grade when I didn’t look like the cheerleaders and decided to try and be beautiful by wearing makeup and straightening my hair. And then with hair- I can’t remember the last time it felt like fun!

I desperately want to reclaim the joy that is to be found in self expression and how we present ourselves to the world, but it’s so entrenched in making myself acceptable that I’m not sure where to go from here.

One day when my eldest was just starting to walk and climb and move around upright, I realized that the pants I'd put her in made it impossible for her to lift her leg up onto whatever it was she wanted to climb on. And that very moment I said fuck it to kid fashion, which is particularly ridiculous for little girls in so many ways I don't have the energy to rant about right now, and decided to put her in leggings and sweatpants and whatever let her MOVE HER WONDERFUL BODY. To this day (she's 7 now) she refuses to wear jeans because she doesn't like how the button feels on her stomach and so I hunt down elastic-waisted warm pants (also another rant -- do only boys deserve to be warm in the winter, FFS?!) and will continue for as long as this is what she wants.

I have also given up wearing anything that makes me feel uncomfortable in my own body and I tell my daughters this regularly. Baby steps, but big steps, and I'm going to keep on walking.