Welcome to the now-weekly audio newsletter! It’s like a podcast in your email. You can listen to the episode right here and now, or add it to the podcast player of your choice and listen whenever. And just in case you don’t like listening (or that’s not accessible to you), I’m including a transcript (lightly edited for clarity) below.

Audio newsletters are now coming out every Thursday. But starting next week, they’ll be for paid subscribers only. If you’d like to be one of those people, click here. If you’re wondering what “paid subscriber” means, read all about it here.

Virginia

Hello and welcome to another audio version of Burnt Toast! This is a newsletter where we explore questions (and some answers) about fatphobia, diet, culture, parenting and health. I’m Virginia Sole-Smith, a journalist who covers weight stigma and diet culture. And I’m the author of The Eating Instinct and the forthcoming Fat Kid Phobia.

Today I’m really pleased to be chatting with Anna Lutz, a dietitian who specializes in eating disorders and family feeding in Raleigh, North Carolina. Anna also blogs at Sunny Side Up Nutrition and co-hosts the Sunny Side Up Nutrition podcast with Elizabeth Davenport and Anna Mackay. Welcome, Anna, it's so good to have you here!

Anna

I’m so glad to be talking with you today! Thank you so much.

Virginia

I’m bringing you on today to talk about growth charts. I hear from parents of kids who are low on the growth chart and are getting pressured to move them up higher, and of course, I hear from lots of parents whose kids are in the 90/95th percentile and are being told that this is a huge problem.

And I think there’s a weird mindset, which I see from both from parents and pediatricians, that somehow our goal is to get everyone into the 50th percentile. So why don’t you tell us a little bit about what growth charts are supposed to do? And what are the misconceptions that you see coming up about them?

Anna

The way I like to explain growth charts is that they are made up of data pulled from thousands and thousands and thousands of children, that gets put into a chart that we can read, as a visual representation. And each time your child goes to their doctor for their well child visit, they’re plotted on this chart. And so if you take your eight-year-old to the doctor, they’re plotted, weight for age, let’s say it’s the 25th percentile. All that means is if you had 100 eight-year-olds in a room together, 75 of them would weigh more than that child and 25 of them would weigh less. So it’s putting them on a bell-shaped curve at that moment.

What we know is, over time, most children follow their own curve. So for example, this child, most likely, from age two to 20, will most likely fall somewhere along this 25th percentile. Now, there are exceptions to that, and we can get into that. But I think you hit the nail on the head. Growth charts do not mean that we’re all supposed to be at the 50th percentile. All it does is look at a population of kids, and see where does your child fall? And their point on the growth chart is just information.

Virginia

Breaking it down like that, it makes me realize that it also really only tells you this one data point about your kid. And we give this data point a huge amount of weight, right? I mean, we think this says whether they're healthy or not healthy, but the way you’re explaining it, it’s got nothing to do with that.

Anna

Exactly. And, you know, it’s going to depend on, are they in the middle of a growth spurt? You know, what is happening at that particular moment, when you happen to take them to their well child visit? Did they just have a stomach bug for the last two weeks, and they’ve lost some weight that they’re going to regain pretty easily in the next month or so? Well, that plot point is going to look really different than if you had taken them to their well child visit a month from now. So I really like to help people see it as information that we can interpret. I think there is some value in it. But sometimes we misinterpret it, and put too much value on it.

Virginia

And you and I have talked before about the way growth charts were constructed. In terms of the populations that they’re based on, they don’t necessarily represent kids today that well.

Anna

Right. The CDC growth charts that we all are using came out in 2000. So now, they’re 21 years old, and they were based on data that was collected before that, clearly. I’m not sure what the plans are for making new growth charts, but just having that information is important. They are really big sample sizes, so that's a positive thing, you know; they were created using data from lots of children from that time period, across the whole United States. But again, if we’re taking one child, and we’re comparing them to a huge population, again, it’s just information. If you're thinking about a very specific demographic, it may not make sense to compare this child in a specific demographic to the whole United States population.

Virginia

When I looked it up, I saw that the data for the BMI-for-age chart was collected somewhere between the 1960s and the 1990s. And it was predominantly white kids that were in their samples at that point. So again, this is going to be very not reflective of lots of kids today.

Let’s talk a little more about when kids fall off their curve, or jump up their curve, all the different negative ways that it gets talked about. You mentioned something like a stomach bug should not be cause for alarm, puberty is another time where kids often appear to be losing their curve or their trajectory in some way. So talk a little bit about why that’s not a time to panic.

Anna

Right around puberty, a few years before, a few years after, there’s—for both girls and boys—a jump in height and a jump in weight, and the rate of height gain, and the rate of weight gain is higher. But again, these growth curves are all based on averages. If you have a child that goes through puberty earlier than average, their increase in rate of weight gain and increase in rate of height gain is going to be earlier. So it’s going to look like they’ve veered above their growth curve. And if you have a child that has a later onset of puberty, they’re going to look like they start to fall off their curve, because they’re not gaining in height or weight at that same rapid pace that this average visual representation shows. What happens is, usually, after puberty, the child kind of goes back to where they were. And again, that’s typically, every child is different.

Virginia

I hear from lots of parents, and I’m sure you do, too, that around age 10 is when the pediatrician says, “Well, let’s think about a diet” or, “we’re concerned about this big jump they’ve had.” And it’s sounding like what you’re saying is, first of all, a) diets for kids are always a terrible idea, and b) this may not be any kind of problem, this may just be where they are.

Anna

With a 10-year-old, you might not know yet that this child is going through an earlier puberty. It just might be this kind of “jump in their growth curve” that’s the first indication that they might be going through an earlier puberty. And that’s not all that abnormally early, just earlier than average. So yes, we all need to take a deep breath and trust that the body knows what it’s doing. And, you know, growth curves, I like using them, because I think they can give us some information. But I don’t think we need to kind of hold them up as the be all, end all.

Virginia

I had a question from a reader saying her kid had always been in the 60 and 70th percentiles, and when they went in for their checkup, post-pandemic, he’s jumped up to the 80th percentile. I think this was a six year old. And the pediatrician was immediately very alarmed about this and immediately jumped to, you know, it’s all the junk food, it’s the pandemic, and the way there’s so much snacking and went to this whole place with it. That feels like several leaps.

What are you hearing right now, in terms of how people’s fear about the “pandemic weight gain” is fueling this?

Anna

I feel like it’s putting blinders on us trying to talk about what’s important. You know, I think people’s weight changed during the pandemic. First of all, you know, you and I have talked about this, but: Kids’ weights were supposed to change. So first of all, yay. But, for children and adults whose weight went up maybe more than “expected,” I don’t think that’s the conversation that needs to be happening. We need to look at how are we all doing with our mental health, how are we doing with taking care of our bodies? I would expect for people’s weight to change in a year that our schedules changed so much. So what I worry about is how this hyper focus on that change over the last year is keeping us from having the conversations that we need to be having about how the pandemic has affected all of our mental health and well-being.

Virginia

Absolutely. So this may be a symptom of something going on with your kid, but the solution is not to cut out snack foods. That’s not going to deal with the underlying stuff.

Anna

Exactly. That’s how I like to think about it, this information from a growth curve is some information. It’s like a little flashing yellow light, like something might be going on, let’s be curious about it, it could be an indicator of something else. But we can’t only try to just turn off that light, and then assume everything will be okay.

Virginia

It’s like, if your “check engine” light comes on, saying yes, I will be putting duct tape over that!

Anna

Exactly. That doesn’t solve it.

Virginia

I’m interested too in how often I hear that seeing kids in a higher spot on the growth curve immediately translates to a conversation about food. This actually happened with my younger daughter who’s always been on the higher end of the growth curve. And when she was around, you know, 18 months or so, my husband took her in, and it wasn’t our usual pediatrician. I think at that point, she was 90th percentile or wherever she was. And immediately, the pediatrician looked at her spot on the growth chart and turned to my husband and said, “So is she eating a lot of white foods?”

Anna

18 months old? Virginia! Goodness gracious.

Virginia

I knew you’d love that. By the way, at that point, she was a very eclectic eater who tried everything. My other child, who’s in a small body, tends to be the “white food kid” in our house. And this is not to shame white foods—they’re great! But he immediately saw her body size and made this assumption without asking questions, without gathering more information. And, you know, it was a baseless assumption. I think naming that as what it is, which is fatphobia, is really important.

Anna

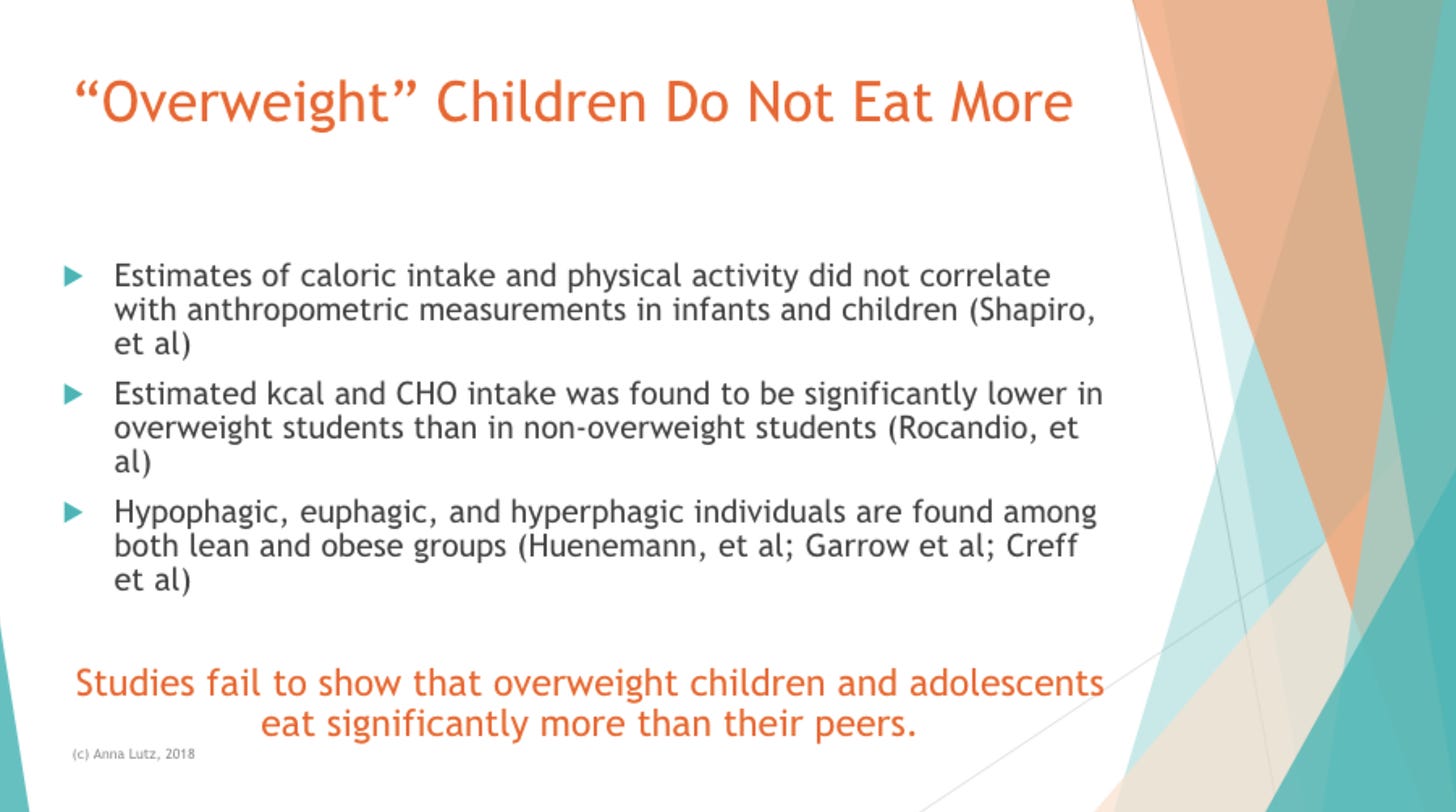

It is. There is research that shows that children in larger bodies do not eat more than children in smaller bodies. [NOTE FROM VIRGINIA: This research can be found here, here, and here.]

This assumption that because someone’s in a larger body, the pediatrician then needs to figure out in what way that child is “eating too much”—it’s not even based on any fact that children in larger bodies do eat more. It’s just amazing that that’s exactly where we all go. And, to be realistic, unfortunately, that’s how pediatricians are being trained right now. Their whole training needs to be adjusted.

Virginia

Yes, it really does. I’m going to link in the transcript to the letter that you’ve put together that parents can take to their pediatricians. But let’s talk a little bit about how parents can take the focus off weight in these appointments. What are some strategies for navigating that?

Anna

I really like to encourage parents to ask their pediatrician not to discuss weight in front of their children. You know, these concepts are super abstract. They’re confusing, even for adults. So if you have these two adults, the doctor and the parent, sitting there looking over a chart saying this is too big, this is too little, what’s going on? Is your child eating too many white foods? It can be super confusing and scary to a child. The whole message is: There’s something wrong with this child that the doctor is so worried about, that the parent needs to figure out how to fix.

There’s the letter that I wrote with Katja Rowell on our website that you can email to a doctor, or you can print it out and hand it to them. What I’ve done with my children is—I said it verbally when the children were younger, and then before I take them in to their well child visit, I send a quick message through the patient portal. And I just say: “As a reminder, please do not discuss weight in front of my children. If you have any concerns, feel free to print out the growth chart and we can talk about it privately.” And I’m still amazed that when that conversation is taken out of the visit, so much more important stuff can be discussed.

Virginia

Because then you can actually talk about things like mental health and these other factors. I think that’s great. For someone who hasn’t had a chance to do that, or the message didn’t get through, which can also happen, and it comes up during a visit anyway, is there language you like to use to help change the conversation, shut it down? What do I say in the moment, if it’s coming up in front of my kids?

Anna

That’s a great question. I think I would say, “That is not something I’m concerned about, but we can talk about it later if you’d like.” I’d say something like that, or I would say, “I’m not concerned about how my child is growing, let’s move on to something else.” I do want to acknowledge, I have a lot of privileges—I mean, my kids’ doctor knows what I do for a living. So there’s a lot of reasons that I feel comfortable doing that, and it might be harder for other people. That’s one reason we wrote that letter, to make it a little easier. You can hand it to someone and the research is all laid out. But any way you can steer the conversation to something else is helpful. And if the doctor is not open to it, is it a possibility to find a different doctor? Again, that might not be a possibility, but consider it.

Virginia

And if they go the food route? The mom who wrote to me was saying the doctor’s immediate comment was “no more juice boxes” without asking how often they even have juice boxes. You as a dietitian can navigate that really easily, but what are some talking points we can use? How do we push back? I think the food shaming is hard because you feel very attacked. It’s “oh, God, I’ve been caught out doing this bad thing.” And it’s hard in the moment to remember that there are no good foods and bad foods. How do I communicate that to a doctor?

Anna

That’s a great question. I think coming up with a line that feels true to you ahead of time can help. So could it be, “I’m not concerned about my child’s eating.” It could be, “if you want to talk more specifics about my child’s food, we’ll need to talk about it later or on email.” But not getting into the nitty gritty of all those questions about—I just went last week, you know, it’s the juice, it’s the “how many fruits and vegetables are they eating? Are they drinking milk?” And for a more sensitive child, they’re gonna start to latch on to these messages.

Virginia

Yeah, I’ve heard that kids will come home and say, “Mommy, the juice is bad.”

Anna

Exactly: “Why are you giving me that, I don’t understand?”or “I don’t eat enough vegetables.” For a sensitive kid who maybe is a “pickier eater” and they hear the doctor saying these things, it can feel super scary. If you are worried about your child’s eating, then maybe say, “Is there a referral you could give me? Is this a conversation we could have later?” I just don’t think it’s appropriate to have it when your 4, 5, 8, 9 year old is sitting there.

Virginia

One line I started to use is “she’s really good at listening to her body.” I kind of figured this out when my older daughter was going through her early feeding challenges, and as we were getting to sort of firmer ground with that, that’s how I’d answer the nutrition questions. And now I do it for my younger daughter, too. Because I feel like that way I’m not even getting into it with you about fruits and vegetables or juice or anything, it’s just, “she’s really good at listening to her body.” And then whatever food shaming the doctor said, at least my child has heard me affirming that they trust their bodies.

Anna

That’s awesome.

Virginia

It’s been helpful. I can see the doctors looking puzzled, but that’s a little bit enjoyable to me.

Anna

Maybe you’re planting a seed?

Virginia

Yes! Well, thank you so much, Anna, this was a great conversation, I think there’s lots of really helpful stuff in here. Where can people find more of you and your work?

Anna

Check us out at sunnysideupnutrition.com, that’s where we write about simple cooking and family feeding. And then also the Sunny Side Up Nutrition podcast.

You’re reading Burnt Toast, a newsletter by Virginia Sole-Smith. Virginia is a feminist writer, and author of The Eating Instinct and the forthcoming Fat Kid Phobia. Comments? Questions? Email Virginia.

If a friend forwarded this to you and you want to subscribe, sign up here:

Share this post