"Nobody Looked At the Largest Mom In the Room."

Navigating anti-fat bias in eating disorders, and at Mommy Wine Night.

Disclaimer: You’re reading this column because you value my input as a journalist who reports on these issues and therefore has a lot of informed opinions. I’m not a healthcare provider and these responses are not meant to substitute for medical or therapeutic advice.

Q: What do you think is an appropriate way to broach fatphobic language with a straight-sized person who has a history of disordered eating?

I have a sibling who has struggled with anorexia in the past and though they have recovered somewhat, they still use a lot of fatphobic language (mostly in relation to themselves but sometimes others as well, primarily in talking about what kinds of bodies they find attractive).

I'm never sure quite what to say. Because I don't have their experience I don't know exactly what's going on in their mind around their body and don't want to trigger anything. And, it feels bad to say a version of "don't say that/use those words/etc. about your body!" to a person who struggles with body image when I have never really struggled with it. But I know it's also wrong to just let it go (which is what I probably do about 90 percent of the time).

The few times I've attempted to say something have been received with some version of "who do you think you are to talk about fatphobia to someone who had anorexia?" I would appreciate any insight you may have.

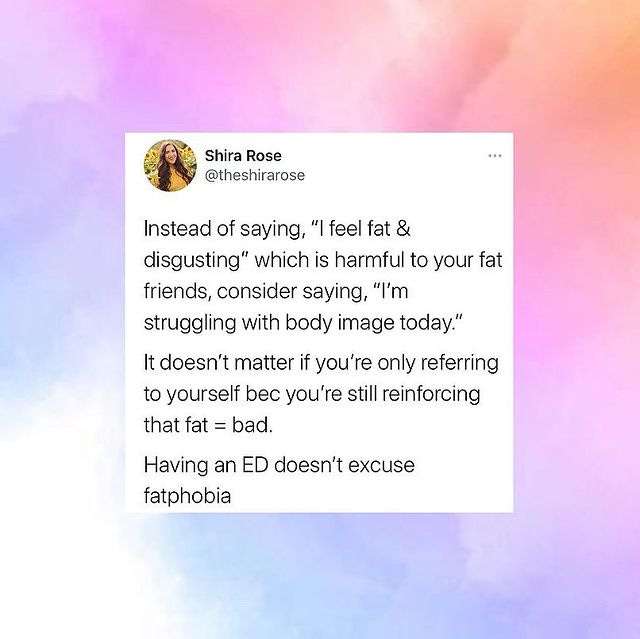

I haven’t had this conversation in real life with a family member. But I have had a version of it online, in comment sections, every time I’ve written about thin privilege—and so has every other fat activist and anti-diet writer. Consider the comments (but also CW/spare yourself the drama) on this post from fat positive eating disorder therapist Shira Rosenbluth, LCSW:

Shira’s post is important, and reminiscent of one of my favorite Julia Turshen pieces, where she writes: “It hit me one day like a splash of cold water in the face. I had only ever felt two things in my life: happy or fat.” We are all socialized to say “I feel fat” instead of naming our actual emotions. And for folks with anorexia,1 the process of replacing that language (and the related anti-fat behavior of restriction) with a more honest and accurate discussion of feelings can be terrifying and brutal. “People living with anorexia nervosa are often at war with their conditions,” explains Jaclyn Siegel, PhD, a social psychologist who studies the lived experiences of people in eating disorder recovery, as well as the psychology of prejudice at San Diego State University. “Their thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and capacity to process the harm of their actions may be dramatically affected by a) the condition itself or b) malnutrition.”

But, Shira and Jaclyn—who both have lived experiences with their own anorexia, in addition to their professional expertise—agree: Having an eating disorder isn’t “a moral pass to perpetuate weight stigma and fatphobia,” as Jaclyn puts it. “Having an eating disorder doesn’t mean you are incapable of being considerate,” says Shira. “And treating people with eating disorders as if they are incapable of insight and improvement is infantilizing and not actually helpful for them.”

The tricky thing to hold together here is that your sibling can be both harmed by fatphobia, in the ways it has taught them to weaponize their weight and food, and cause that harm to others. They are perpetuating fatphobia in the ways they talk about bodies. (We’re doing this even if we only talk about ourselves, by the way; your fat friends are listening.) That doesn’t mean they aren’t also struggling. But—and I truly do not mean this metaphor to make light of mental health struggles—we teach little kids to sneeze into their elbows (and hey, wear masks!) for a reason. We can be sick and still not want to spread that sickness to others. In this way, I don’t think it’s hypocritical for someone with an eating disorder to be a fat justice advocate, therapist, or otherwise active in fat liberation; you can be deep in your own personal struggle and still know your values. And you can also know your behaviors aren’t matching up to those values and still struggle to change them, because this shit is hard. Sometimes, understanding the larger impact of our behaviors can be a helpful tool towards recovery.

It'’s also worth noting that we can be struggling desperately with our own bodies and yet also benefit from thin privilege in terms of how we can access and navigate the world, as Aubrey Gordon explained on the podcast last year. And a thin person making fatphobic comments has even greater potential to do harm because of this privilege. Again, this doesn’t mean that a thin person with an eating disorder doesn’t deserve our support and compassion. But they can deserve our support and compassion and cause harm to fat folks—who also deserve our support and compassion.

So. How do you begin to navigate this conversation? You are right that chastising or correcting isn’t the way to go. “Calling out their comments to shame them into behavior change is not supportive to your sibling’s recovery,” says Jaclyn. But you can validate their feelings and offer a reframing. If your sibling says, “I feel so fat today,” Jaclyn suggests responding with: “I’m sorry it sounds like you’re having a tough time right now. But can I ask you something? What’s wrong with being fat?” This might gently segue you into a deeper conversation about anti-fat bias. If you are fat, Shira suggests explaining in a kind but direct way how their comments impact you: “When you call yourself a fat slob, I wonder how disgusting you think my body is.” (If you’re not fat, or don’t feel comfortable talking about yourself, you could also reference a fat loved one here.) Make sure they know you’re not ascribing harmful intent: “I know this is not your intention. You’d never want to hurt me!” And then offer an alternative: “It would feel different for you to say, ‘I’m struggling with my body image right now’ instead of ‘I’m a disgusting fat pig.’”

Your sibling’s comments about what kinds of bodies they find attractive are also worth (again, kindly) challenging—and may even feel like an easier place to start than their self-deprecation. “Attraction is a complicated topic because no one owes anyone sex or romance or their attraction,” says Jaclyn. “But interrogating the roots of ‘personal preference’ in the context of attraction can be a helpful exercise.” As I’ve written before, nobody just doesn’t want to be fat. And nobody just happens to think that thin people are hotter than fat people. These are not quirky idiosyncrasies; they are biases we’ve learned from our fatphobic society. So here you might be able to dig deeper. Jaclyn suggests questions like: “Why do we favor one body type over another? Where are we getting our information about what or who is sexually attractive?”

If any kind of direct conversation feels too fraught, you can talk more generally about your own un-learning process and offer to share books, articles, or podcast episodes you’ve found helpful. The hardest part for me in these conversations is that they don’t always work. At least, not right away. Some part of my brain is always hoping for the instant conversion—and the odds of that happening are basically none. So don’t be shocked if your sibling shuts you down initially. “If they don’t respond in the way you’d like, don’t push or get angry,” advises Jaclyn. “You’re their sibling, not their therapist. Perhaps they will take this conversation into therapy with them next week.” Keep in mind how long it took for you to question these basic assumptions like “fat equals bad,” and understand that the eating disorder will understandably lengthen and complicate this process for your sibling.

And don’t give up hope. “I remember gently telling a 14-year-old who was calling herself fat and disgusting in group, that maybe she could reconsider the words she used,” Shira says. The girl’s first response was defensiveness and anger. But she was ultimately able to reflect, and express her feelings with other words. “People can be thoughtful about the language they use!” says Shira. “And it helps them too.”

Q: Recently at a moms’ wine night, two thin moms, one fat mom, and me, a plump mom, sat around talking about how we respond to our kids pointing their fingers and asking, in that volume only a toddler can reach, “MAMA WHY IS THAT MAN FAT?”

We all agreed that we prefer to focus on the manners of pointing/bringing questions about others’ bodies to mom and dad in private. I admitted that I find it easier to respond to kids who call me fat, because then I can joyfully say, “Yes, and I love my body.” I explicitly said I don’t want my kids to think some bodies are better than others, and everyone agreed. And then, I’m thinking of how I have practiced responding to “She has brown skin!” or “He’s missing a hand!” with a warm acknowledgment of “Yes and aren’t all bodies wonderfully different!” not a hushed taboo we-don’t-talk-about-that. It’s easy to do with race, not so much with body size, because our culture doesn’t want to believe darker skin is bad but somehow our culture does seem to want to believe larger bodies are bad. Racism and anti-fat bias are both issues, but anti-fat bias is still met with such justification.

But…not one of us looked directly at the largest mom in the room or asked her directly what she thought. It felt taboo to even acknowledge the obvious, which is that she is fatter than we are, so she has more lived experience than we do on this matter, and probably the most useful opinions. I don’t know her or how she relates to her body or whether she identifies with the word fat, and it was just so…darkly fascinating that even as we’re discussing how we want our kids to relate to all bodies as good, anti-fat culture was preventing us from doing the same amongst ourselves. If we’d been having the same discussion about a neutral or broadly-admired trait, it would have gone differently. I’d love your thoughts.

Oh God. I read this and a little bit died for you all. Because oh, I have been here—with fatness, but also with race, or sexuality or probably any other marginalization—and I bet, if they’re honest, most newsletter readers have too. There is such a particular vibe that comes from well-intentioned people trying to talk thoughtfully about an uncomfortable issue and yet remaining so uncomfortable that they end up perpetuating the very harm they are trying to avoid. And yes, your fat friend noticed. She noticed the lack of eye contact and the lack of direct questions. I can’t say how she felt about it—she may have been glad the conversation didn’t center on her, for a variety of reasons. She also may have been quietly, justifiably fuming at how your discussion ignored her lived experience and existence. And whether she was glad for your silence or furious about it, or somewhere in the middle, she almost certainly did not feel seen.