Last week,

wrote a great piece about which beauty standards she has divested from (pedicures, daily makeup, bras!) and which beauty standard she still clings to: Hair. She writes:I want to be the type of person who moans dramatically about humidity making my hair unruly. I want to push thick clumps of hair out of my face as I garden. I want to PILE hair atop my head. I want face-framing waves to escape from a hair elastic and, you know, frame my face. [...] My longing for thick hair also surely has something to do with the fact that everyone on TV has the same hair. And that hair is thick.

I am someone who does get to moan dramatically about humidity and push thick clumps of hair out of my face as I garden. I have a lot of hair (on every square inch of my body, but that’s a discussion for another essay!). And while it is by no means effortless, when I need it to perform, it can look like TV hair. But in reading Sara’s essay, I realized that I cling just as hard to the Good Hair beauty standard as she does. And that’s because divesting from thinness comes at a cost. Anti-fatness is woven into all of our other beauty standards too.

One way I perform the Good Fatty is to have Good Hair.

If you haven’t heard the phrase “good fatty” before, I’ll direct you to artist and activist Stacy Bias for this excellent deep dive into the term. The general consensus definition, she writes, is that “a ‘good fatty’ is a fatty who is trying or at least *believes* they should be trying to no longer be fat.” But good fatties aren’t acting in a void—capitalism and social hierarchies create the pressure to perform this identity. “Each ‘Good Fatty’ archetype that exists is basically an argument or a justification for inclusion in society’s spheres of privilege,” Stacy writes. Because we’ve “failed” to measure up to society’s capitalism-driven standards in one significant way, we try to check as many other boxes as we can. This is both a logical survival strategy in a fatphobic culture, and a manifestation of some lingering internalized anti-fatness. As Stacy explains:

If Good Fatties exist, then not all fatties are bad and therefore we can’t ethically be excluded from society. The problem is, whenever you define something as ‘good,’ you’re automatically defining it in opposition to something else. So the Good Fatty creates the Bad Fatty—who then gets thrown under the bus.

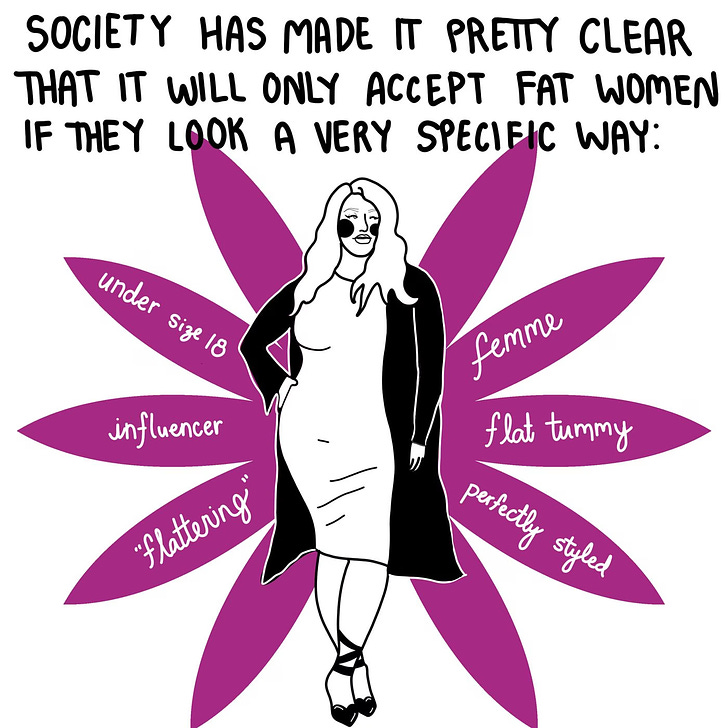

Stacy goes on to identify 12 Good Fatty archetypes1 and they are all worth exploring in detail. But since our topic today is hair, I’ll focus on the Fatshionista. This is a fat person who—because we fall within a certain size range, have financial resources, and/or sewing skills and, I’d add to this list, grooming skills—is able to present as stylish, put-together, on trend.

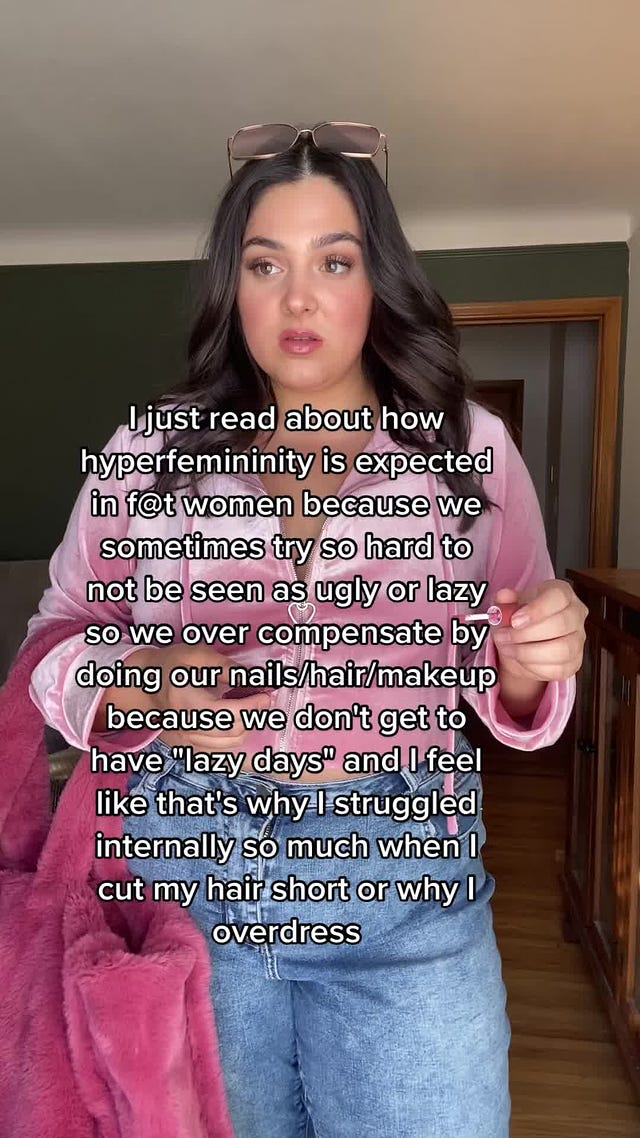

We can read Fatshionistas as subversive. We wear the styles—bikinis, giant dresses, horizontal stripes—that the women’s magazines said would never flatter our figures! We are unafraid to take up space. And, not all Fatshionistas are women or femme. But most Fatshionistas we see on social media sure are, which means that even as we assert our right to participate in fashion as a cultural conversation and form of self-expression, we also uphold a zillion other beauty and gender ideals. Fatshionistas show that a bigger body can be beautiful, but don’t argue for beauty itself to matter less.

This constrains our gender expression: “I wanted to dress more androgynously, but I was afraid of how ‘gender neutral’ clothing would fit on my large bust, curvy waist and wide hips,” wrote Maggie Spear in this 2019 comic essay for TheLily.com.

Fatshionistas also perform significantly more appearance-related labor than our thinner femme peers. Wrote Marie Southard Ospina for Dazed, in 2017:

It’s okay for thin women to slip into stretchy jumpsuits, wear plain tees or crop tops with a trusted pair of mom jeans, or eschew makeup altogether in favour of a more ‘natural’ look. It’s okay for thin women to be emblems of the ‘lazy girl trend,’ an entire aesthetic rooted in looking like you haven’t spent more than two minutes getting ready because you’re just that chill. Nevermind that the word ‘lazy’ is one often used to shame or ridicule fat people, who are perpetually accused of being undisciplined and inactive. Both sartorial and regular, old laziness seem perfectly acceptable if delivered in thin, conventionally pretty packages.

And access to fat fashion still requires many kinds of privilege (small fat privilege, financial privilege, time privilege if you’re going to sew or thrift). It’s unclear at best whether the rise of the fat fashion influencer is making any real dent when it comes to increasing clothing accessibility for all sizes.

Stacy doesn’t identify a beauty-specific Good Fatty, but I’ll argue for Good Hair to be classified as a Fatshionista Subtype. (Elaborate Skincare Routine might be another?) And arguably, with even less redeeming value. Because while Fatshionistas break some rules, Good Hair Fatties only uphold a long list of anti-fat norms:

We wear our hair long, because we’ve bought into the myth that short hair on big women isn’t feminine or sexy. To be clear, that’s sexy to men, so this is also a Venn diagram of anti-fatness, homophobia, transphobia and misogyny. Performing femininity is a way to access social capital and power otherwise off limits to us, due to our fatness.

Our hair is also long because we have complicated feelings about our necks and chins. We might resist wearing it up, even on super hot days. Long hair is armor.

Our long hair is straight, or wavy in a very carefully controlled manner (barrel curls, not air-dried, please) because we’ve been told that big, wild hair on a big girl makes us too big all over.

A lot of us go blonde, because the aesthetics of Good Hair, like all beauty standards, are white and Eurocentric. Hello, intersection of anti-fatness and racism, specifically anti-Blackness!

We might spend a fortune on highlights and regular salon visits. This is to cover grays, because if you’re already fat, you can’t also be old. It’s also to look as polished as possible. No slovenly, unhygienic fatties to be found here.

If we are elder millennials or Gen X, we for sure resisted the return of the middle part because 90s lady mags taught us that side parts were “slimming.”

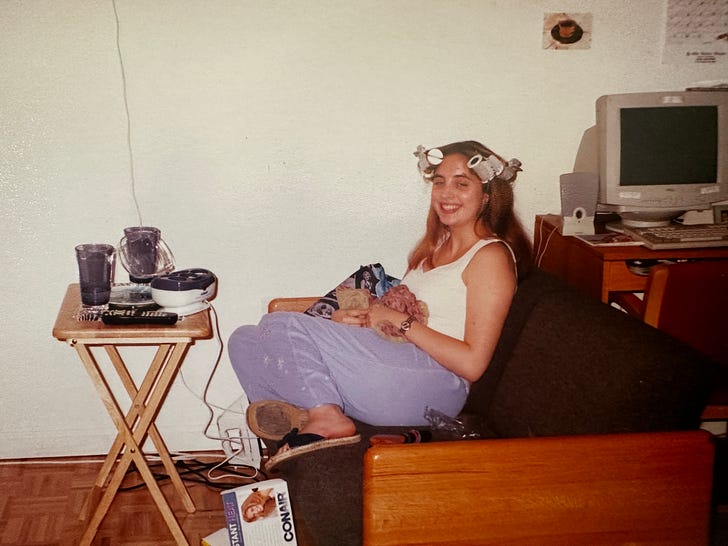

And we pay for all of this with our dollars (those salon visits!) and our time and labor. Like when I had to tell Sara last week that I couldn’t finish editing an episode of our new podcast (drops tomorrow!) because I had to go blow dry my hair in order to attend my children’s school Halloween parade. I own both a full set of “blow out” products and styling tools, and a full set of “curly day” products and I plan a lot of my week —both work commitments that involve being on camera and social commitments—around my hair washing schedule. Until I started writing this essay, I didn’t even realize how annoying that is. I’ve lived this way since the sixth grade, which is when I started styling my bangs every morning before school. And absolutely since “Legally Blonde” came out during my freshman year of college and converted me into a heat styling devotee.

We also pay because the Good Hair standard—like all beauty standards—can never actually be achieved. As I commented immediately upon reading Sara’s piece, I cannot pile my significant quantity of hair atop my head the way she longs to do, because that giant messy bun look is only possible if you have extensions and/or a very small head relative to your quantity of hair and I have neither. TV hair is not real. Instagram hair is not real. Every celebrity or influencer with hair you love is wearing extensions or a wig. (Best quote from that Hollywood Reporter article I just linked: “The camera eats hair, so you always need more.”)

Part of why Good Hair is so hard for me to release personally is that I get close enough that it seems like I’m just one new product purchase or one new styling routine away from getting all the way there. I never do, just like the diet never works. But this is also why straight-sized people can be the most reluctant to abandon diet culture. And why white women are so often complicit in so many harmful institutions.

I would say my hair meets many (but never all) Good Hair criteria maybe two days per week. The rest of the time I’m just wandering around in some liminal state of dry shampoo plus frizz plus a strategically placed clip. It loses volume when it gets greasy, it loses sleekness when it gets humid. In other words: It is the hair of a human being who is sweating and existing and moving through the world without the aid of a full-time stylist and no line item for $1,000 hair extensions in any of her contracts.

This essay is not a guilt trip about your hair labor (or mine).

We don’t owe anyone else our hair decisions, just like we don’t owe anyone our bodies. And body autonomy means we’re all allowed to decide what amount, and which kinds, of beauty work we want to participate in, just like we’re all allowed to decide when we want to opt the fuck out.

Last week on “We Can Do Hard Things,” Glennon Doyle talked about finally breaking up with Botox after she realized her wrinkle-free forehead was giving her wife Abby agita about her own more visible aging. “It was a microcosm moment that made me understand, very acutely, what we do to each other [with our beauty work],” she said. “I just suddenly feel so excited to not be a part of that. [...] I’m just excited to be in quiet solidarity with just resisting the tyranny of ‘You are not allowed to be a human being.’” I appreciate Glennon’s take, especially, as she noted, hers is a face we see a lot, and we need more highly visible faces and bodies that have divested from a few beauty standards if we’re ever going to make any of this truly optional. But I would have appreciated it even more if she had acknowledged all of the privilege —thin, white, Good Hair— that makes it easier for her to step back from that one particular edge.

So I don’t see my relationship with my hair changing in any profound way. I’m in a long-term committed relationship with an amazing hair stylist who I long ago out-sourced most of my hair decisions. I saw her last Friday and we talked about some of the ideas in this essay. She patiently refused to cut my hair short this month, because she has seen me through “my life imploded, let’s get bangs” before, and isn’t about to let me do that again. Even more, we talked about our divorces and our kids and a whole bunch of stuff that has nothing to do with hair, because every two hour salon appointment with her is also a visit with a dear friend. But I’m happy to pay her well to give me Good Hair because while my hair is still a lot of work (let me say it again: There is no such thing as effortless Good Hair) I so appreciate how her time and talent enables me to think so much less about my hair, most of the time.

Because what I’m really buying, with my time, labor, and salon bills, is an insurance policy against the higher cost of letting my hair go. When I texted with Sara about this essay, she said the same thing: “I spend so much money on highlights because my natural hair color is sad as fuck dishwater blonde,” she says. “In order to embrace my natural hair, I’d be potentially feeling a certain level of something every time I looked in the mirror. So much of this feels like an effort to protect us from unwanted feelings.” Another friend told us about a news anchor friend who lives with “50 percent fake hair” all the time in order to do her job. My mother couldn’t let herself go gray until after she retired because the cost of visible aging in Corporate America is far too high. I pay to have an expert carry my Hair Mental Load even though it leaves me complicit with problematic beauty standards because how my head looks is just not a place where I need to take a big visual risk right now.

But it is useful to examine our participation periodically. So that we can decide if we still want to do this work. So we can consider if it brings us any true joy along with the effort. And so we can be clear-eyed about what the world requires of our hair —and what our adherence to a beauty standard says to the world.

What I Put On My Head

I’m sorry, I know we’re deconstructing a beauty standard today but almost 20 years of women’s magazine training just will not let me leave you without a product sidebar. It would be blasphemy even though I don’t have advertisers or sponsors for all the reasons, and haven’t even gotten my act together on affiliate links.

So here’s what I use on my hair: