It's the Same Problem.

There is no "emotionally healthy" weight loss for kids. (Plus, fat kayakers!!!)

Disclaimer: You’re reading this column because you value my input as a journalist who reports on these issues and therefore has a lot of informed opinions. I’m not a healthcare provider and these responses are not meant to substitute for medical or therapeutic advice.

Q: I thought of you last night as I had a very heartfelt discussion with a friend. We were talking about body positivity and all the things I am doing to keep my straight-sized daughter healthy and avoid an eating disorder. She shared that she has an opposite problem with her son. He has gotten quite big and it's affecting his mental health and his ability to do things he likes. For example: He no longer wants to go to the pool. And at camp he wanted to kayak, but you aren't allowed to do white water kayaking until you can flip and recover the kayak, and he couldn't practice that because he needed to be in a canoe due to his size. He has expressed interest in losing weight, and they want to support that and support his ability to do all the things he wants to do, BUT they want to do it in an emotionally healthy way.

Do you have thoughts on how she might support him in a way that feels good to him and doesn't stigmatize or damage his mental health? But, also, how can she help him reach his goals (whatever they are)?

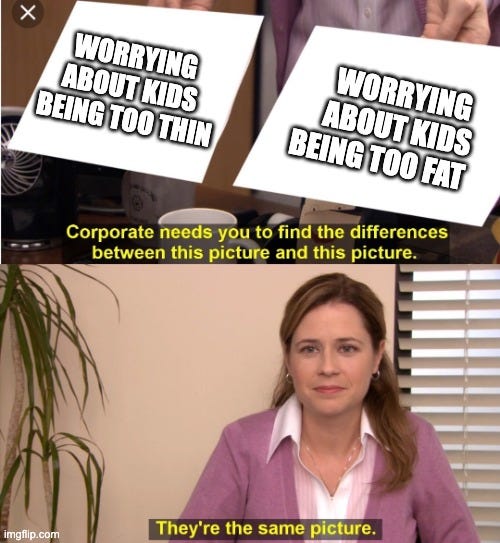

You are worrying about how to keep your thin daughter from becoming too thin.

Your friend is wondering how to help her fat son lose weight.

These situations are not “opposite problems.” They are one and the same problem.

You are both parents who love kids who are struggling to feel good about their bodies in a world that tells them to take up less space. You both want them to feel better about their bodies. You both want to protect their mental health. The problem here is that you are both letting anti-fat bias define what this “better” would look like. This is why you can see quite clearly that the goal for your daughter is to avoid dieting at all costs—but are pondering whether that same risky behavior is the solution for her son.

Framing these situations as “opposite problems” privileges the struggle of the thin child as somehow more genuine and deserving of help. She needs to be protected from the evils of dieting and eating disorders because after all she isn’t even fat. (I know you didn’t use that phrase, but if I had a dime for every email from a parent of a thin kid that does include it, I would not need paid newsletter subscribers.) But when actual fat kids are told they shouldn’t be fat, a part of us thinks, well, yes. All of their problems, we assume, could be fixed by just losing some weight.

This is dangerous because it’s wrong: Diets don’t make us happier. Teenage girls who dieted “at a severe level” were 18 times more likely to develop eating disorders than those who did not, according to a three-year study on almost 2,000 kids published by Australian researchers. Even moderate dieters were five times more likely to progress to an eating disorder; future studies have replicated these findings repeatedly. More recent research has taught us that kids in bigger bodies may be even more likely to engage in disordered eating than their thinner peers, no doubt because we are so often convinced they “need” to eat this way to lose weight. Even when they don’t contribute to eating disorders, dieting messes with our minds and bodies: I wrote more about the harm caused when we put kids on diets here and here.

And it’s dangerous to assume weight loss will solve a fat kid’s problems because it’s deeply fatphobic: Why does a thin child get mental health support and tools for insulating themselves against the pressures to be thinner while a fat child is offered none of the above? Why is he instead steered directly towards the same toxic messaging you know to be harmful for your daughter? Why is the fat kid’s body and mind somehow less worth protecting?

Now let’s consider the ways we might perceive this child’s weight as impacting his health and happiness—because in both examples you gave me, the problem is not his body, but the way our culture treats fat bodies.

Example A: He doesn’t feel comfortable going to the pool. This isn’t a physical limitation. Fat people can be great swimmers. The real question is why your community pool doesn’t feel like a safe space for fat kids. Maybe it’s attached to a gym that pushes a ton of weight loss marketing.1 Maybe he’s been bullied at the pool (and this could mean teasing from other kids, but also unsolicited comments about his body from adults). Maybe he’s outgrown last year’s swimsuit and feels self-conscious asking for a new one. Maybe he knows his parents want him to swim more, consciously or not, because they want him to lose weight and that’s taking all the joy out of the experience.

Example B: He couldn’t learn to flip and recover a kayak because the camp put him in a canoe instead. I also do not know how to flip and recover a kayak because I never went to a camp that taught kayaking (former theater kids represent!), so I turned to YouTube to help me understand this concern and lo and behold this fat guy with a lawn mower has a super helpful video explaining exactly how to flip and recover a kayak in a bigger body.2 I also found this extremely thorough and fat-positive video that explains why kayaking is absolutely possible for fat folks and walks through the different types of kayaks that work best and are designed to be size-inclusive. And my favorite fat kayak resource is the delightful Parker explaining how to get in and out of a kayak without falling over, which honestly always seems like the hardest part?

(Post-publication note: An astute fat kayaking reader named Madeline noted below that all of these resources are geared towards recreational kayaking, which is different from white water kayaking. But Madeline assures us that fat folks can do white water kayaking too! So my larger point stands even if my grasp on the nuances of the sport is a bit shaky.)

This is not meant to be an exhaustive dive into the world of fat kayaking, though I am so pleased to now know that it exists. The real question we need to ask here is: Why doesn’t his camp have kayaks that fit bigger bodies? Why doesn’t his camp have staff trained to help fat kids learn the same skills they’re teaching thin kids? Why does this kid have to feel like a failure in a canoe when it took a 30-second Google search to see that he absolutely can learn to kayak, no weight loss required?

The answer, of course, is anti-fat bias.

I know it might feel daunting for your friend to tackle this bias at the community pool, or to demand the camp (that she is presumably paying for!) stock better kayaks. We are so used to viewing fatness as a failing, as something we don’t talk about, and as a matter of personal responsibility that it requires a significant mindset shift to start saying, “Hey, my kid doesn’t feel safe or supported here, and that’s what needs to change.”

I know it’s further complicated by the fact that this kid has stated his own weight loss goal. As parents, we’re used to thinking that supporting our kids means supporting their goals and dreams, and as people in diet culture, we’re used to thinking that a fat person losing weight is a reasonable way to improve body image and health, which sound like nice goals to achieve. But there is no “emotionally healthy” way to support a child’s weight loss goal because intentional weight loss isn’t healthy or safe for kids—no matter what their starting weight. It doesn’t undermine his body autonomy to push back against this desire to lose weight, just like it doesn’t undermine our kids’ body autonomy to make them wear seatbelts or get vaccines. And just like it doesn’t undermine your thin daughter’s body autonomy if you were to stop her from dieting.

It is important to validate the feelings and experiences that are causing this kid to say “I need to lose weight.” But we can do that without endorsing the idea that he should lose weight, by naming the anti-fat bias he’s experienced and by talking about how hard it is to have a body, especially a fat body, in a culture that tells us we’re doing that wrong. This reframes the problem, which is the first step towards helping him let go of his internalized fatphobia. Because I suspect he’ll keep saying “I need to lose weight” until somebody says to him: “Actually, your body is not the problem here.”

You voted and the results are in: We’ll be reading ESSENTIAL LABOR by Angela Garbes for the August Burnt Toast Book Club! Mark your calendars for Wednesday, August 31 at 12pm Eastern.

Burnt Toast Giving Circle Update! We’ve raised almost $25,000 which is so utterly amazing. You can, of course, still join the effort here. And if you’d like to learn more about why we chose Arizona, the candidates, and our path to victory, The States Project is hosting a virtual conversation TONIGHT, featuring our endorsee, Lorena Austin, Democratic candidate for LD-9. RSVP here to attend.

This is true of one of the pools in my area; I went as a friend’s guest recently and then had to unsubscribe from a flurry of texts encouraging me to join so I could “shed pounds for summer.” LITERALLY JUST WANTED TO COOL OFF, thanks Stephanie.

Warning that he does make a few annoying anti-fat comments like "we're not in the best physical shape!" But it still seems useful.

Who knew that watching Parker kayak would make me sob uncontrollably? I have spent so much of my life avoiding fun activities (pool, kayaks, etc.) because I felt like I was too fat to participate. I’m now 47 and don’t give a flip anymore, but the pain of a lifetime of sequestering myself is still there…hence, the sobbing.

I would flip my shit (and a kayak for good measure) on a camp that othered my kid out of an activity in which he wanted to participate because of his size. And then I would send them the video of Parker.

I bought a pool membership this summer, our first in a new town, and was absolutely expecting it to be a hit to the self-esteem every day for three months. Instead, it's the opposite - so many different body types and shapes and sizes all just trying to enjoy the water. I'm glad my 4.5-year-old is seeing it. Of course, I can't guarantee that kids aren't involved in bullying, but I'm not seeing obvious signs of it. Another thing that makes me happy is the variety of swimsuits out there right now - I see adults and kids, thin and fat, in everything from rash guards and board shorts or skirts to bikinis/tiny trunks. I also think for young kids the emphasis on showing skin at the pool is so much less now that rash guards are a part of life, and I hope it makes some people more comfortable in the water - I know it would have made me a very happy teenager to be able to put on a rash guard. Perhaps that sounds bad - feeling fat? cover up! - but to my mind it's more of an equalizer. If everyone's wearing shirts in the pool, wearing a shirt in the pool no longer becomes what you do if you're the fat kid. Add to that not having to slather sunblock on my squirmy kid constantly and I'm a big rash guard fan.