You’re listening to Burnt Toast! This is the podcast about anti-fat bias, diet culture, parenting and health. I’m Virginia Sole Smith.

Today I am chatting with Vashti Harrison, number one New York Times-bestselling author and illustrator of Little Leaders, Little Dreamers, and Little Legends — about her newest picture book, Big.

Big is such an important contribution to the representation of Black girls, and of fat kids, in literature. And this is a really moving conversation. I absolutely loved getting to know Vashti, hearing about her process, and about everything that went into this book. I hope it is really helpful to you in thinking about how to have conversations about anti-fat bias, but also about anti-Black racism and adultification, with your kids.

If you’re enjoying the podcast, make sure you’re following us (it’s free!) in your podcast player! We’re on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, and Pocket Casts! And while you’re there, please leave us a rating or review. (We like 5 stars!)

AND - we have signed copies of Big and several of Vashti’s other books in the Burnt Toast Bookshop right now! Plus you can get 10 percent off that purchase if you also order (or have already ordered!) Fat Talk! (Just use the code FATTALK at checkout.)

And don’t forget to check out our new Burnt Toast Podcast Bonus Content!

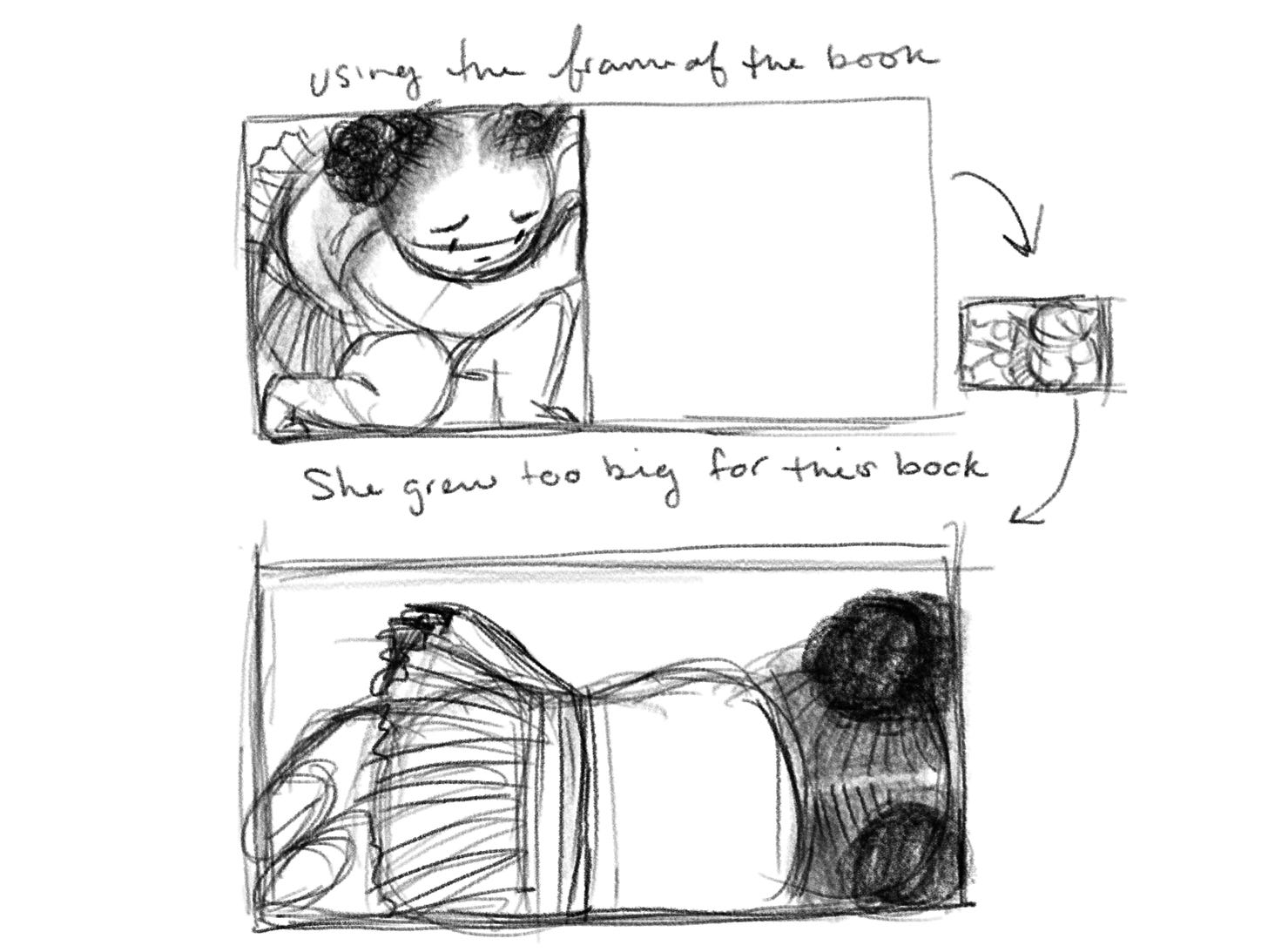

This week we have stunning behind-the-scenes illustrations from Big in its early stages. You don’t want to miss this.

Episode 116 Transcript

Virginia

Your book Big is a major favorite in our house, I just found it in my daughter’s bed the other day. It really, really means a lot to our family. Why don’t we start by having you tell listeners a little bit about yourself and your work?

Vashti

I am primarily an author and illustrator of children’s books—although author still feels like an awkward new term for me! I feel like I was thrust into the world of writing, but I came to it through drawing. I’ve always expressed myself through images.

My background is actually in filmmaking. I used to make experimental films, primarily shot on 16 millimeter, very kind of like artsy fartsy, definitely in a world outside of the commercial art world and definitely outside of making work for young people. But through the process of learning all of the tools and techniques and traditions of formal art making, I learned a lot of discipline and how to tell stories and when I rekindled a love for drawing I felt like so charged and excited to be expressing myself through my hands. It felt so different than making movies, which felt laborious and always required lots of gear and help. I felt so empowered to be able to tell any kind of story I wanted through illustration.

Not to jump right into the politics, but around the time of the Trump election, I just felt like I wanted to be making positive work. I wanted to be making work for young people. It just became only thing I was excited or interested in creating: Images and stories that felt like they were uplifting for young people.

Virginia

I think 2016 had that impact on a lot of us. I can relate to that feeling of: The world is burning, how am I going to put anything good into it?

Vashti

I felt powerless. I felt like I can’t do much in this world. I can’t change too much or too many people. But if I can create enough images that connect to people… Weirdly enough, I was thinking about Winnie the Pooh. I was thinking about Pikachu. I was thinking about characters that when people see them, they say, “Oh my gosh, I love that character!” That’s what I wanted to create for Black children. I wanted people to see these images of Black children and have that same response.

Virginia

I think a lot about how Winnie the Pooh is a sort of stealth fat icon. He’s very proud of being short and fat. There’s a lovely way to read both the books and the movie as being fat positive. And yet, there is this huge problem in children’s media. Kids’ books feature talking animals more often than they feature Black kids and Black girls, for sure. We need more, and we need different.

So tell us about Big. What inspired this story in particular?

Vashti

Well, around the time that I started working on my first book, Little Leaders: Bold Women in Black History, I read this study that came out of the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality called Girlhood Interrupted. It was my first introduction to the term “adultification bias.” That is the perception that some children are more adult, more mature, more responsible, and more knowledgeable than their age would suggest.

Adultification is inherently racialized, because it happens at a disproportionate rate to Black children and especially Black girls. The study found that adults view Black girls as young as the age of five as less innocent and more adult than their white counterparts. This results in adults believing that Black girls need less nurturing, less protection, that they need to be comforted less, that they know more about adult topics—and the list goes on.

When I read this study, I felt so emotionally wrenched because I remember being a really shy kid who took a really long time to come of age. I just thought about how harmful it is, or would have been for me to have been presumed old enough or mature enough for things that I was definitely not ready for. I also thought about all the different metrics that feed into this bias: Skin color, height, voice, body shape, size and weight. I just feared for the girls that were being judged for being too something: Too big, too tall, too loud.

I was thinking about this intersection of adultification bias and anti-fat bias and I felt so charged to tell a story that centered on these things because I felt like I was going through my own emotional journey. I was reflecting on my my body and feeling like I wanted to make art that spoke to self-love and confronted how anti-fat bias had affected me. I didn’t know how I would tell that story, but the idea was ruminating while I was working on the other books.

Those were nonfiction books and required a lot of research and I had agreed to do one every year. So I was just working for a couple years straight. Around the same time, I illustrated Sulwe by Lupita Niyong’o, which is about colorism. Which is a heavy, heavy topic to put in a children’s book.

So I think in the process of working on all these other books, I was thinking about how to tell my own story. This is my first piece of fiction and it’s my first picture book that I’ve written and illustrated by myself. The process of working on other people’s books and those few years of just kind of ruminating on the ideas helped it all kind of cook. It was slow cooking for a while while some other ideas are in the Instant Pot, this one was a slow cooker.

Virginia

I love that you brought up the Georgetown research, I want to talk about that a little more.

I also was really moved by that study when it was published and I use it a lot in my book in talking about bias against fat kids and particularly Black girls in schools, how it comes up in dress codes and in the conversations around puberty. And something that really moved me about that research was hearing from the girls themselves. One girl said something like, “I get dress coded way more than anyone else because I’m in a bigger body. I know that something that’s low cut on another girl goes unremarked on and on me it’s a problem.” That is so important.

I quote a couple of them in my book because that is the huge problem with research on these issues often, right? We don’t hear from the kids who are experiencing this. So I recommend everyone spend some time with that research. It’s important to hear from these girls. I think we often don’t realize how much kids are exquisitely aware of how all of these biases are being used against them.

Vashti

Yes. I can say these words “adultification bias,” and “anti-fat bias,” but I was connecting with the stories of actual girls. Georgetown Center put out a really approachable, accessible short animated video where they use some of those words and it’s like, it really just puts it it out there for you to really understand, like, these aren’t just datasets. These are real people, these are children who deserve so much more than what they’re being offered. So I think that’s what I wanted to capture in Big.

Virginia

So what is the story of Big?

Vashti

Big follows the story of a young girl who, when she’s first born, the people around her, the adults around her, use such positive words of affirmation. “You’re such a big girl, you’re a big girl now.” And that is a good thing. I wanted to talk about how, at a certain point in most girls’ lives, particularly in America, “big” goes from being a positive thing to being a negative thing.

I wanted the inciting incident to be something that felt nearly innocuous. It’s an event, it’s something that happens, and she is changed after it. She takes in the words that people say to her, and it changes the way she she feels about herself and experiences the world. It is a story about the words we say to one another and also about how we offer children or how we don’t offer children the space to change and grow because of these weird expectations about what innocence looks like.

Virginia

As I’m listening to you talk, I’m thinking about how it is very easy to read Big as a somewhat straightforward story of this girl who loves ballet and is too big. Because you use text quite sparingly, the pictures are telling the story. So it’s easy to do one read of it. And as I’ve read it over and over with my daughter, I’ve gotten deeper and deeper into it.

So now talking to you, I’m understanding just how radical the foundation of this book is. It is easy to pick up Big and think, “Oh, it’s a book about little girls and ballet.” It’s actually something way more subversive and more powerful than that.

Vashti

I think that is something I kind of struggled with, because I worried about all of the subtext. I wondered, is this too adult? Am I writing the story as an adult who has gone through and processed all these feelings and making something that is not quite for children? There is a surface level story and then there’s a subtextual story.

On the surface, it is about a young girl who is full of self love and that changes after an incident on the playground. She starts to internalize these negative words she hears from the people around her and it makes her physically grow on the page to the point where she doesn’t fit anymore. At that point, she has to be confronted with not fitting, with people having problems with that. Fortunately she finds enough self love. She finds a way to identify what she loves about herself and what she knows to be true about herself and lets go of the things that she knows are not true about her and she makes more space for herself.

It’s not a book about ballet. Ballet is a tool that is a metaphor in this story for the thing that we love. In this case, it felt important to show that the thing that she loves is also about freedom, about moving your body freely. Her joy gets taken away by these negative words from the people around her. And they are just passing comments, I don’t think many of the people know that those words stuck with her and are changing her, changing the way she feels and exists.

One of the one of the things that changes for her as her body starts physically growing—for anyone who hasn’t seen it, things start changing for her and she grows larger than the size of her bed. Then in the next image, she’s 10 feet tall and can’t fit in her desk at school. That’s a visual image that’s kind of silly, but I was thinking about the way that Black girls get pushed out of school. They are not offered the opportunity to have different bodies or be silly and be loud because they are being judged for being too much or too something or too adult and are regularly getting punished at higher rates. That is directly correlated to the school to prison pipeline. So there are things that I was thinking about in this book that you wouldn’t quite know if I didn’t tell you, but it’s all there for me.

Virginia

I love that you’re saying maybe it’s not a book for kids. I think the best children’s books often aren’t entirely for kids, or at least work on many different levels.

This is not a perfect comparison by any means because your book is doing something quite different and more groundbreaking, but I wrote a piece recently revisiting Eloise with my daughter. Eloise was not intended to be a book for children. Kay Thompson actually didn’t even like kids and was really adamant about the fact that she wrote it for her gay cabaret fans. And of course children adore it, right? Little girls adore it and people embrace this rambunctious little girl’s story, which is powerful, especially so at the time.

I think there’s something really valuable in kids books when the author has this whole other mission. And I think kids do get it.

I think the reason I loved Eloise as a little girl is because she represented some freedom to me that I wasn’t feeling in my own life. I was such a good girl, not a rule breaker, ever. It was helpful for me to see this representation of femininity that wasn’t just perfect little good girl. I think the kids reading your books are having an even more profound experience of seeing themselves and seeing you put into pictures. The emotional experiences they’re having in their lives, that’s huge. It’s huge.

Vashti

Yeah, I appreciate that. It is the highest form of praise when I hear that a kid loves the book, that a kid is reading it over and over again. I was just scared throughout the entire process if I was doing the right thing.

Mainly because I read a review—you’re not supposed to read the reviews, but I read one. When I illustrated this book by Lupita Nyong’o called Sulwe that is a fictionalization of her childhood experiences growing up as the darkest person in her family. In this in this story, this little girl has to go on this adventure and hear the stories of night and day and in the end she learns to love the color of her skin.

But I read this review by a parent who said, “My kid did not have any anxieties about the color of her skin before this book, and now she does, and it’s all your fault.” And I was like, it is all my fault. But I also believe this book couldn’t have created something that didn’t exist. So I, I try to keep that thought a little bit closer to me because it is my fear that this book would incite an anxiety or a fear that wasn’t present in a child before

Virginia

This was something I wanted to ask you about. I do a lot of work reporting and thinking about how we talk to our kids about the issues of anti-fatness and diet culture. Often parents will say to me, “It’s too early. I don’t want to bring this up now because I’ll put this in their heads.”

But I feel that the research shows quite clearly, with both adultification bias and anti-fat bias, that kids are learning about it really young.

Vashti

I’m reminded of when folks say “It’s too early to talk to your kids about race and racism.” But for for Black children, that is rarely an option. It is a thing that exists and we’re going to encounter it no matter what. It comes from a place of privilege to say “It’s too early for my kid.”

Obviously, each individual adult and child experience is different. And as a very sensitive kid, I definitely would have appreciated someone taking care in the way they spoke to me about this. But when addressing these these larger, heavy things in our society, it is rarely an option that we won’t encounter it.

I think particularly with Big, we’re talking about the way that adults use words with children. It is so ubiquitous in our society to talk about children’s bodies as this good or bad thing. And the call might be coming from inside the house. I’m trying to appeal to all of us to address the way we use this language. I think in order to dismantle hatred, we have to address it. f you’re not aware of all of these things, how can we properly fight it together?

Virginia

I think often, when parents say, “It’s too early,” they’re really saying, “I’m not ready to have this talk. I don’t know what I’m going to say.”

We need to give parents—and this is more my job than yours—more tools on how to have the talk so that they can tackle it. And texts like Big are this gift because they give you a way into it.

This is another maybe tangential example, but I was just talking to a mom this week who was really anxious about letting her 10-year-old see the Barbie movie because she said, “I’ve always been so careful not to expose her to diet culture and to these body ideals. Is the Barbie movie age appropriate? Can she handle that? She has so much confidence right now and I don’t want to destroy that.”

And I totally get that instinct. We want to protect our kids. But the Barbie movie is doing some subversive stuff. It’s not going far enough, but there’s a lot you can talk about in that movie with a 10-year-old.

But I could see it was a lot of her fear of how will I navigate the conversations that come up there? I think we need to be a little less afraid of the hard conversations.

But anyway back to your more important and more powerful book! Something you do so well is show adults talking about her body. And we see her absorbing what they’re saying. I think maybe some of this discomfort too comes from parents knowing “I’ve probably said something I shouldn’t and I know my kid really did absorb it.” And you hold up a mirror to that so powerfully.

I really love the moment at the end of the book where she tells the grownups she doesn’t want to change her body and that they’ve been offering the wrong kind of help. That just feels so radical for kids to see a kid advocating for herself like that.

Vashti

I struggled with knowing exactly how to end this book. It doesn’t have that sort of third act triumphant win, but it’s there. It’s just way more quiet. I think on an unconscious level, I needed to share that the journey towards self love is a personal one. I remember having conversations with my editor about how the girl gets there about maybe needing another character or another conversation to achieve a clear story arc. But I kept pushing back against that. I couldn’t quite verbalize why she needed to just be alone.

Looking back on it now, I feel like to include other characters, other adults or other kids, would be too easy. It would turn them into the heroes or villains of her story. And in the end, she saves herself. It’s quiet but it’s resolute.

In the final spreads, she dances and moves her body. She is unhindered and taking up space and completely free within herself. I think I just knew that there were going to be people who were going to say, “I can help you, I can fix you, I can make you be smaller!” And I wanted her to have this look on her face like, “Oh, you just don’t get it It’s okay. Because I’ve got it. I’m okay.”

Like, girl. I wish I could be that strong. It’s an aspirational thing.

Virginia

It also shows a very real facet of this, which is, often as we are working on becoming resolute and becoming accepting of ourselves, we also have to accept that people who love us can love us and get it wrong. You show her being able to love them, even though their advice and their solutions for her are not the right advice and solutions. I think that is a tension that’s something we’re all navigating all the time.

Vashti

The people that were working on this book with me—my agent, my editor, my art director—to be fair about the publishing industry, they’re all predominantly white women. And I just think there was a misconception that this was a book about body positivity. They were expecting it to have a much more triumphant positive end, and while I do appreciate the body positivity, this wasn’t about that. It wasn’t just about changing her own mindset about herself. It was about dismantling a systemic oppression against big bodies.

That felt like a much bigger thing to tackle that one person can’t do alone. But the journey towards self love, at least, I felt was very personal and quiet. The book is a very internal story. We see everything through her perspective. The other people aren’t fully rendered, everything is in this shade of pink. They’re sort of the ideas of other people. It doesn’t feel like we’re in the grounded real world. For me, that was to further push the idea that we’re inside of her lens, her perspective, her world. could have looked very different. It could have been a very different story if it was about body positivity.

Virginia

I think we have picture books that are more firmly body positive and I think they can be useful additions to these conversations with kids. And I think body positivity has left so many people out. It has failed to deal with the systemic bias of it all in such a profound way. We don’t need to be teaching kids that there are simple solutions to any of this and that all you have to do is love yourself. What a disservice that is because that’s not going to help you survive the world. It’s nice to have, but it’s not the solution.

I am curious though, as you were working on this book and clearly as it was such a long process, as you said, did working on it change your own thinking about bodies? Did it shift your relationship with your own body in any ways?

Vashti

I think this is an aspirational book. I can look to this girl as a hero, for me. I think she gets there, and I’m still on this journey. Even the process of writing it, I just felt like I was picking at an open wound. It just made it even harder to create, but I think it was a hopeful kind of creative process. My own journey has so many ups and downs. And, you know, I’m still struggling very day, I feel like am I going to be a hypocrite if I start going to this new gym? I don’t know. It’s hard.

I don’t have too big of a community around me. My closest ally is an untrustworthy ally. They’re talking about Wegovy and joining the next diet. So it feels like I am constantly bombarded with diet culture. I’ve always felt like that in my own family. It’s really hard to try to be on a journey towards essentially neutrality. When, in my family, everyone values, like, working extra hard towards something. And so it can feel like, to them, I’m a failure. Or to them, I’m giving up or something.

I don’t know, I’m still parsing all this stuff out. But I think that’s what’s helpful about making art is letting everything out and sorting through all these feelings through storytelling.

I think my journey is sometimes like one step forward, two steps back. Sometimes it’s two steps forward, one step back. I think it’s so easy for me to want to stand up for other people. And it’s just still so hard to do that for myself.

Virginia

Oh, absolutely.

Vashti

I want to make a world where children do not have to face any of the diet culture nonsense that I had to face all through childhood, all through my family home life. I will go to the ends of the world to say they deserve as much time and space and care to have their bodies change and grow and look however they need to, as long as they are happy and healthy. But it’s a lot harder for myself to do that.

Virginia

I think a lot about how it’s really important that people know you can be in this fight and you can be working towards this, even if you’re struggling yourself. I think there’s often this perception—and I think this is one of the things body positivity has not helped with—that in order to be a good advocate on these issues, you need to totally love yourself, you need to never be dieting, you need to be completely divested from diet culture, and have this unimpeachable resume of body acceptance.

Vashti

Sometimes I think about that for myself, like, oh, gosh, I’m supposed to look this way. I’m supposed to have this for the people who look to me. But.

Virginia

But I mean, it’s a stealth diet mentality to hold yourself to that standard of body positivity perfection. That’s the other people telling us we have to follow all of these rules in order to be worthy, in order to fit in. You can be doing this in your own way. You can be messy. We are humans, we are messy.

Vashti

I think what you’re saying applies to so many other things, too. In my career I feel like I skyrocketed really, really fast. I didn’t get to spend enough time being a student of my field. I don’t have all the answers. I really don’t feel like I have the authority on these things. So, honestly, it feels like to expect perfection is a fallacy.

Virginia

All of this as a survival strategy, right? Participating in diet culture, beauty culture, whatever. It’s all just what we have been told we have to do to be safe and survive in this world.

And how much you can let go of all of that is going to be such an individual thing. Some people can let go of a lot of it really easily. That’s probably people who have a lot of privilege in other ways protecting them. Other people who can’t let go of a lot of it, even if they can recognize all the problems in the system and don’t want to be supporting that system.

Well, I am so grateful for this book I already adored it and talking to you about it gives me so many more layers of appreciation for what went into this. I understand it’s probably stressful to hear this, as you just talked about the pressures of skyrocketing fast, but I really think it is an instant classic that we are going to be reading for generations. So, no pressure there, but good job.

Vashti

That is the hugest honor and the biggest fear. So scary.

Butter

Vashti

I’ve got maybe two Butters, and one of them is related to Barbie. It’s the amount of pink that I’m seeing everywhere, which is related to my book Big, which features a lot of pink. And I think you know, it is related sure to ballet, the character in the book likes to dance. But my choice in making the book fully told through this lens is that pink is this girl’s character. This is her. This is this character’s color. I associate this color with her. And through the arc of the book, we see that color. We see glimpses of what it could be when she’s feeling really hopeful and full of love. We see that color get dimmed and it gets grayer and grayer. Then we see it fully return back to its saturation, where she is again seeing a future for herself, and seeing what she knows to be true about herself.

I remember being a kid and pink being so uncool. Like you play with Barbies? Pink, ugh. And I love pink and I like seeing it everywhere. So that is my joy.

And then my my other Butter is right now our economy is somehow being boosted by Taylor Swift, Beyonce, and Barbie fans. I feel so excited to know that people are finding community this way. I heard today that Michaels had a 300 percent sales boost in crafting supplies because of people making friendship bracelets, which is also a call back to my childhood. So I feel really grateful to know that people are crafting and expressing themselves through these things that our culture has often told us are silly absurd, childish, girly things. Crafting and beading and making friendship bracelets. I’m all about celebrating girl power bringing our economy back.

Virginia

I also really love pink. I do have two daughters who don’t like pink but I think that’s a stage. I think it’s a necessary rejection of their mother, it’s fine. Plus, as a feminist, I made a conscious choice not to give them a lot of pink clothes. It’s hard when you have two girls, all of the baby gifts are like pink Mary Janes. I had to draw some lines.

But now that they’re older, and we can talk about all of these complicated conversations, I’m steadily bringing more pink into our home decor and into my wardrobe. So I’m also here for the reclaiming and the rebranding of pink I think is great.

Vashti

Also, in color theory, pink is associated with gentle love and care and that is something that I want for Black girls. And I wanted that for this girl at the center of my story. So sure, pink has its connotations in our society but also I appreciate that when we think of pink flowers that represent nurturing and love I want to offer that to all girls.

Virginia

Well those were amazing Butters. Mine is far more prosaic but it is something bringing me joy right now. It’s a set of photo frames I got off Amazon. I apologize— I’m trying to divest but as we just discussed, we are messy human beings and Amazon Prime does still own my soul.

So these are these clear acrylic picture frames. They’re really chunky and they’re magnetic so they’re easy to open and close and swap out what you want to put in them.

And I got the little four by four inch ones that are pretty small. And Phoebe Wahl has great set of anti-diet fat positive stickers that I picked up recently at my local bookstore. I wanted to do something special with them, so I put them in these frames. They’re so cute just popped around my house now and they’re bringing me a lot of fat positive joy.

Vashti

I discovered these frames somewhere in the middle of the lockdown of 2020, and started putting my little collages in there because I didn’t want to paste them down to look at how delicate they were. They’re perfect for these things. I’ve given a lot of them away at this point but I have a few left around my room.

Virginia

I love that you already know about them! They’re such good frames. They come in a ton of different sizes and are not super expensive. And They’re acrylic so they can’t break which is useful in a house with children and an excited dogs.

Well Vashti, thank you so much. This was incredible conversation. I loved having you here. Tell folks where we can follow you and how we can support your work?

Vashti

I am on Instagram and other platforms as @vashtiharrison. You can find my work and some of my illustrations on my website.

The Burnt Toast Podcast is produced and hosted by Virginia Sole-Smith. You can follow me on Instagram.

Burnt Toast transcripts and essays are edited and formatted by

who runs@SellTradePlus, an Instagram account where you can buy and sell plus size clothing.The Burnt Toast logo is by Deanna Lowe.

Our theme music is by Jeff Bailey and Chris Maxwell.

Tommy Harron is our audio engineer.

Thanks for listening and for supporting anti-diet, body liberation journalism!

Share this post