CW: This essay includes several mentions of specific weights and BMI, in reference to contraception.

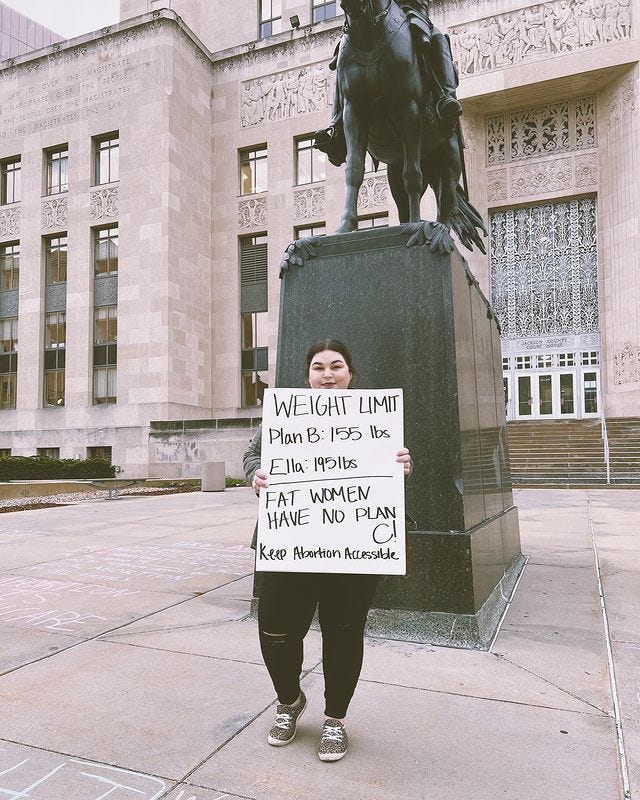

One night when my friend Grace was 23, she had unprotected sex with her long-term boyfriend, James. “We got drunk at a wedding and didn’t use anything,” she says. “Immediately afterwards, it was like, Oh my God, what have we done?” Grace sent James straight out to the drugstore to get emergency contraception. “I took Plan B probably two or three hours later—that’s how fast I got my hands on it.” But a month later, Grace had a positive pregnancy test. Her daughter, Rosie, is now ten years old. And it wasn’t until two years ago, when Grace, now 32, saw a post in my InstaStories, that she finally realized why: “I was probably 160ish pounds at the time,” she says. Plan B’s effectiveness begins to wane at 155 pounds.

The pharmacist in the small town drugstore where James bought Plan B didn’t mention a weight limit. And neither did Grace’s doctors any time she’s discussed using it at a medical appointment. “I’ve used Plan B a few more times since then for extra security,” says Grace, who now has three kids with James—all wanted, but all surprises. “Guess I didn’t need to waste my money because I’m way over the weight limit now.”

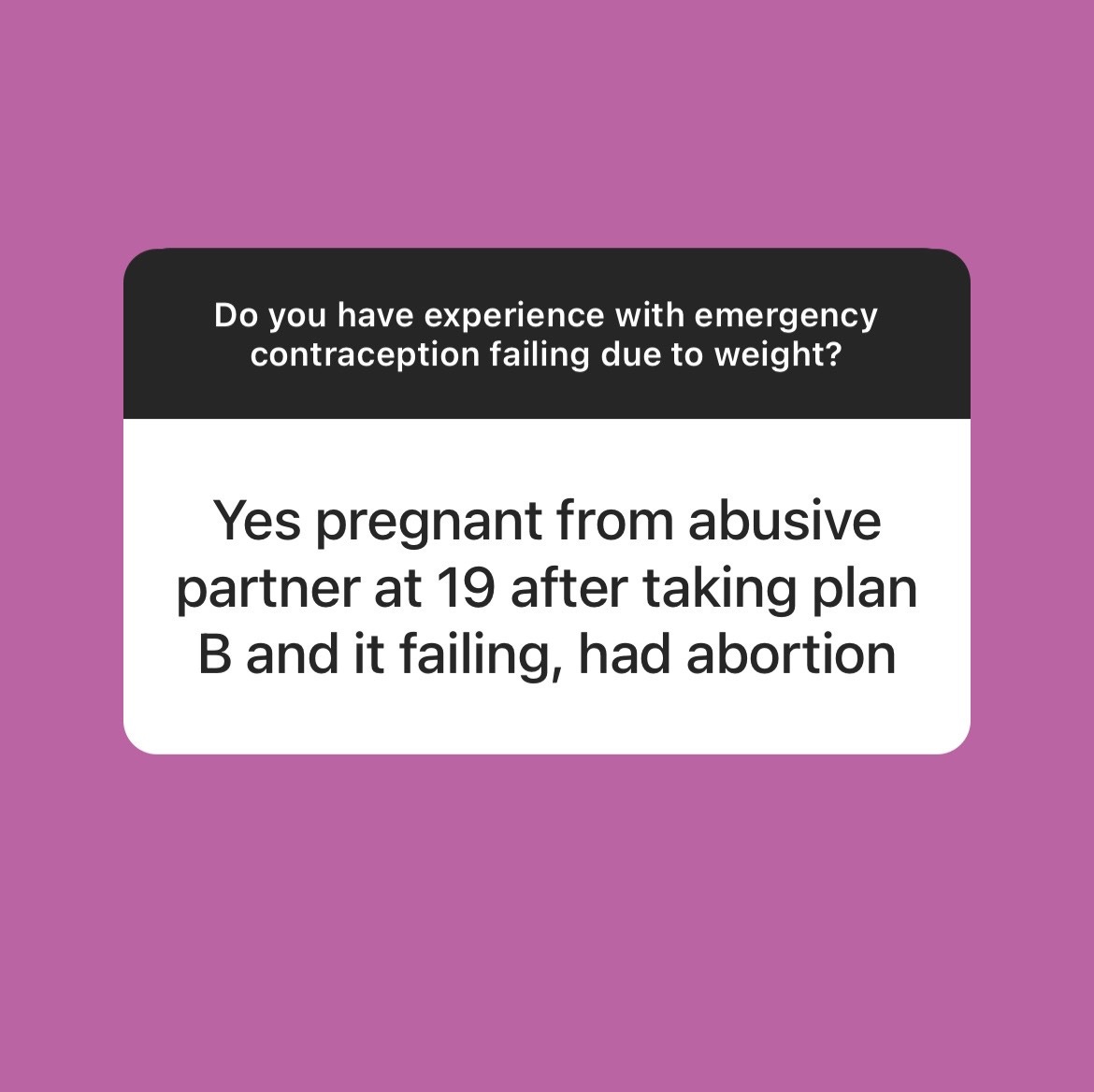

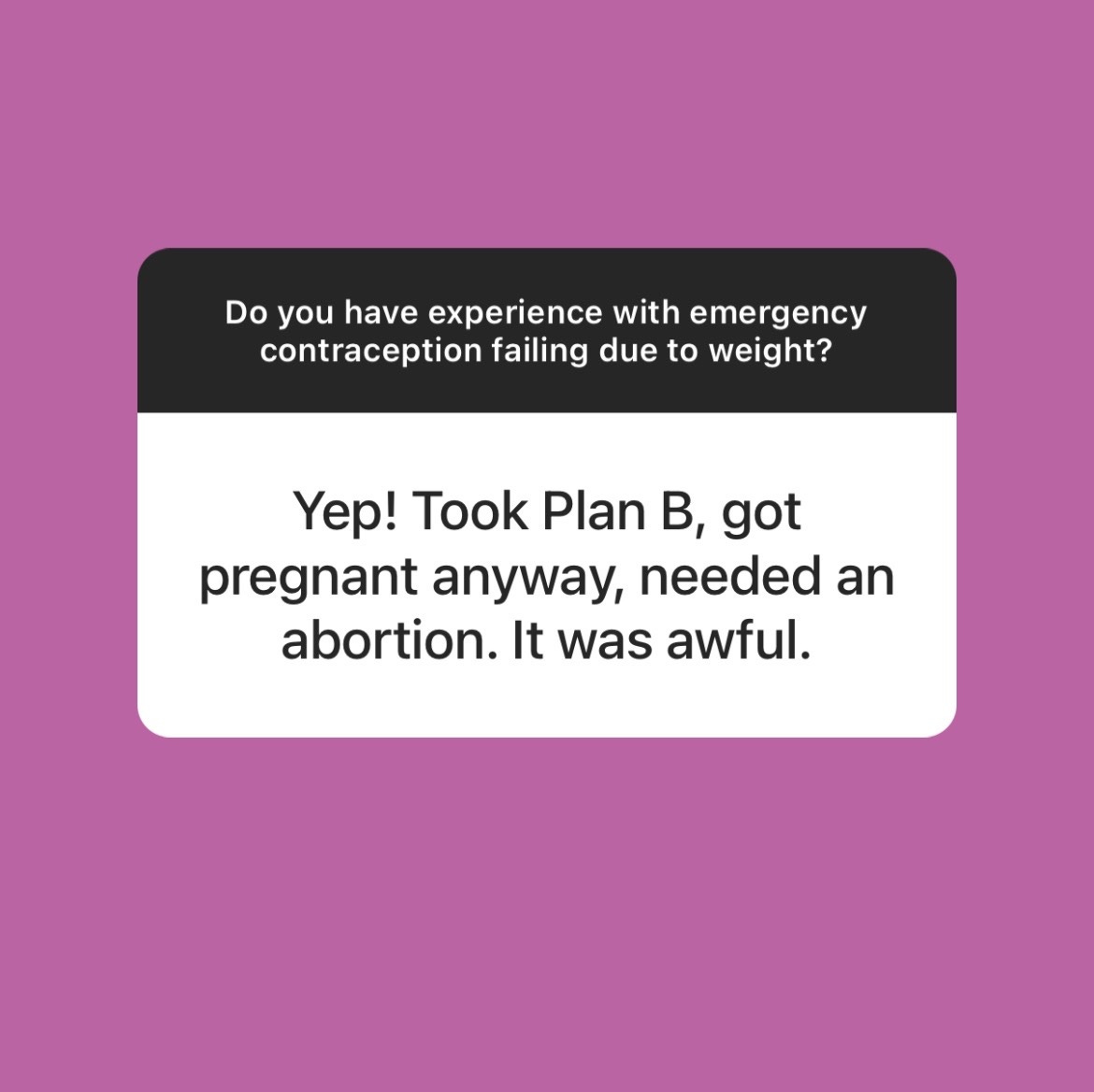

When I polled my Instagram followers, almost 40 percent of them said they had no idea that Plan B doesn’t work as well for fat folks.1 And those that knew often found out the hard way, like Grace. “I got pregnant at 19, from an abusive partner,” wrote one. “Plan B failed. I had an abortion.” Others told me stories of supporting family members through post-Plan B abortions, or of working in healthcare clinics where such stories are commonplace. (The one fun way people have learned this fact: The premiere episode of “Shrill.” Thank you

and Aidy Bryant, doing the lord’s work!)When some 69 percent of women have BMIs in the overweight and ob*se ranges, why is it not common knowledge that emergency contraception might not work unless you’re thin? To answer this, you have to think about how much we don’t care about women’s health, and then add on how much we don’t care about fat people’s health, or the health of other marginalized folks. Oh, and how much pharmaceutical companies will fight labels that might narrow their potential market for a drug: In 2016, the Food & Drug Administration decided that Plan B didn’t need a special warning label about weight because the available data was “conflicting and too limited to make a definitive conclusion.” This was great news for Plan B, which offers this take on their website:

We hold the same belief as the FDA, which states that there are no safety concerns that preclude the use of levonorgestrel emergency contraceptives in women generally, and continue to believe that all women, regardless of how much they weigh, can use these products to prevent unintended pregnancy following unprotected sex or contraceptive failure. The most important factor affecting how well emergency contraception works is how quickly it is taken. When emergency contraception is taken as directed within 72 hours after unprotected sex or birth control failure, it can significantly decrease the chance that a woman will get pregnant. In fact, the earlier the product is taken after unprotected intercourse, the better it works. Emergency contraception is not 100% effective, which is why it is critical that women have a “Plan A” (regular) birth control method or start one if they don’t have one. If you have any further questions, we encourage you to talk to your healthcare provider.

I have spent a long time pondering how a phrase like “we hold the same belief as the FDA” ended up on what should be an evidence-based website. Because the FDA does not believe Plan B works. The FDA has stated that there is no scientific consensus on whether or not Plan B works for higher weight people. The FDA’s official belief on this matter is, “We have no idea.” When Grace and the other women I heard from took emergency contraception to prevent their pregnancies, they didn’t want to believe it could work—they wanted to know it would.

And the scientific evidence we have so far cannot give us that certainty. Women with a BMI over 25 were more than three times as likely as women with BMIs in the “normal” range to experience Plan B failures, according to a 2011 study published in the journal Contraception. Subsequent research published in 2015 and 2016 also documented an even higher risk of failure related to weight. But the authors of a large 2017 study concluded that access to emergency contraception should not be limited by weight category based on their evidence—even though they did find that women with BMIs over 30 had eight times higher odds of becoming pregnant while using Plan B compared to women in lower BMI categories. That seems to be when everyone stopped researching and started believing. In reading through other reporting on Plan B and weight, I kept encountering a general, shrugging vibe of, “but it doesn’t hurt to try?” As one doctor told Glamour in 2019, “[The data] doesn't mean it's ineffective—it means it's less effective.” Except we aren’t shooting for less pregnant here.

The advice is vague and terrible because the science we have doesn’t tell us nearly enough about how hormonal birth control in general works for people at higher weights. When a doctor prescribed the birth control patch to me in my 20s, she offhandedly mentioned I was just a few pounds away from the weight at which it loses effectiveness. “Try not to get any bigger or this might not work for you,” she said, rather than finding me a form of birth control that wouldn’t require a diet. We frame the potential failure rate of these drugs as the responsibility of fat people because after all, this wouldn’t be so hard if you would just lose the weight. But it’s not the patient’s responsibility to make a drug work. “Studies on drug dosing and efficacy need to be better designed to take drug distribution and efficacy for higher weight individuals into account,” says Andrea Westby, MD, a family medicine physician with the University of Minnesota Medical School. “Not doing that is anti-fat discrimination and continues to perpetuate inequities in health outcomes for people of size.” But the science isn’t getting done because, fatphobia.

Dr. Westby says she always discusses the efficacy risks of Plan B when prescribing it to patients, though she leaves the final decision of whether t use it up to them: “I absolutely do not use a ‘weight limit’ to determine who can have access to emergency contraception or other medications.” She also goes over other options, thought they aren’t extensive. There’s Ella, an oral emergency contraception containing ulipristal, which is only available by prescription and which, research suggests, may start to lose efficacy for folks over 195 pounds. Or there is the one truly bulletproof choice: An emergency placement of either a copper IUD (sold as Paragard) or a progesterone-containing IUD (sold as Mirena). “Their efficacy is not, as far as we can tell, affected by weight,” says Dr. Westby. “But getting an IUD placed is more invasive and may be less acceptable to people for a number of reasons—including a clinician’s inexperience with larger-bodied individuals leading to less well-done procedures.”

So fat folks requiring emergency contraception get to choose between a potentially ineffective medication and a potentially painful IUD insertion.2 And the reason we don’t have better options is almost certainly rooted in the way anti-fat bias and morality influence reproductive health research and medical care. We blame anyone for being fat and we blame almost anyone (except cis, straight, white men) for having sex. If you check both boxes and you get pregnant, we’ll blame you if anything goes wrong there, too.

“If we get pregnant, even if that pregnancy is very much wanted, we face even more barriers to surviving our pregnancy and birth,” Linda Gerhardt explained in her Instagram post (and yes, I stole this piece’s headline from her, with permission). I’ve written about the ways medical fatphobia shows up during pregnancy for the New York Times Magazine, and also discussed it here and here on the podcast, but to suffice to say: It’s every step of the way, and often every minute of your labor and delivery experience.

A common argument from the right is that people should “be responsible” about (heterosexual) sex, and if not, be ready to accept the consequences. It’s a flawed premise for so many reasons—namely, how rigidly the right defines what “responsible sex” means for other people, and how “irresponsible” people still deserve healthcare. And: If fat folks can’t trust birth control and emergency contraception to work for us, then “responsible sex” becomes something only thin people get to have. Which makes access to safe, affordable abortions a critical fat rights issue. “Abortion is healthcare,” says Dr. Westby. “If the medications we use to prevent pregnancy are less effective in fat folks because of anti-fat discrimination in drug development, then folks need to be able to access abortion if they do not desire pregnancy.”

And, we need support in making these decisions from healthcare providers who understand how anti-fat bias has eroded our options. Writes Linda:

For me, it's a thorny issue. I am child-free by choice, but I have a hard time separating whether I even want children from the abject terror I feel of how I will be treated if I were to get pregnant. I have seen the looks of horror on doctors' faces when I've mentioned that I wasn't decided about kids yet, the "OH GOD PLEASE NO, DON'T HAVE A BABY," and those faces are what has guided my decision.

The intersection of anti-fat bias and anti-choice ideology already controls the lives of too many people. When we lost Roe, in addition to the thousands of other ways that human rights have suffered, healthcare for fat people with uteruses degraded to a new low.

For Grace, discovering she was pregnant after Plan B failed was terrifying. “I felt very young and not ready and had a miserable pregnancy,” she says. Her mother, herself the result of a teen pregnancy who later aborted her own pregnancy at a young age, “stayed neutral” and helped Grace think through her options. But James’ family was more high pressure: “My now-sister-in-law bought baby clothes and said, ‘don’t have an abortion,’” Grace says. “So I had that in the back of my head.” Grace decided to keep the pregnancy, but became increasingly depressed and dreaded telling people the news. Her friends were getting jobs, moving to the city and going out like people in their early 20s do, while she was suddenly planning a very different life. “Rosie is the best thing that ever happened to me,” she says. “And I needed to know abortion was an option.”

This piece first ran on May 10, 2022, just before the Supreme Court struck down Roe; you can read the original version here. I updated it for today because when I shared about stocking up on abortion pills and Plan B last week, I heard from readers who were shocked to know about the Plan B weight limit issue.

It’s more crucial than ever to get this information out there.

If this piece resonated with you, I’d love for you to tap the “heart” button and/or restack this piece to Notes, so more readers can join the conversation. Thanks for supporting Burnt Toast!

Wondering What To Do Next?

If you have a uterus, talk to your doctor about the best way to protect yourself against unwanted pregnancy in the months and years ahead.

Order abortion pills. Trusted sources: Aid Access, Plan C Pills, Abortion Finder, I Need An A.

Support your local abortion fund (or one in a red state!) and a practical support organization, with a recurring monthly donation if you can.

Plus: Five things to do right now, via

(who is required reading.)

Not a randomized or otherwise scientifically significant sample, but I’ve seen similar chatter across social media.

Okay, a quick note on the pain: The Paragard I had inserted pre-kids is tied with my unmedicated vaginal birth for most painful experience of my life. Post-kids, I’ve had two Mirena IUDs inserted and it was no worse than a Pap smear. I do personally love the peace of mind and ease of life that IUDs provide, but I don’t think science is doing nearly enough work to figure out pain-free insertion for folks who haven’t already had their cervixes opened by a giant baby’s head. (Your mileage may vary; please share experiences in the comments!)

I had a copper iud placed when I was in my early 20s, and it was such a bad experience that it made me decide to become a healthcare provider. I graduated as an NP this year, & wrote a literature review of pain control methods for IUD insertion for my masters project. Y’all, there are effective topical meds that significantly reduce pain and I am so deeply mad that not all clinics use them! I keep asking otherwise rad providers why they don’t offer anything beside ibuprofen & they say the data on effective pain control is mixed (which was historically true!) but I found that lidocaine cream *consistently* lowered pain scores in a number of recent small trials.

TLDR pain with iud insertion varies widely and for some folks is real rough, lidocaine cream is awesome & takes two minutes to put on a cervix, and I think the reasons it’s not used for all intrauterine procedures is because misogyny is baked into the medical system.

That 2017 study is driving me up a goddamn wall. So little funding for this, and then we get this one piece of evidence for which they concluded "yes it's true but we're not sure if the obese people just received worse care or something and, overall, don't worry about it." I'm taking some license with the abstract here but it's not far off. Pretty enraging.