You’re listening to Burnt Toast! Yes, even though it’s Tuesday!

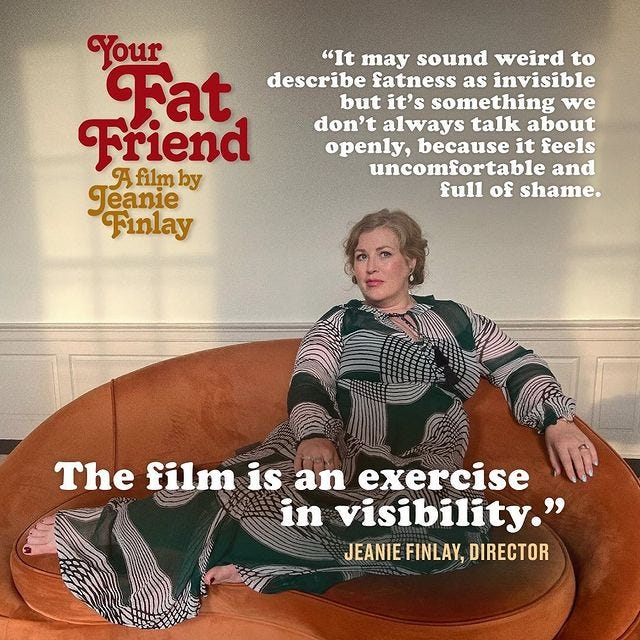

We’ve got a podcast episode for you today, even though it is not our normal Thursday podcast day, because I was so excited to be able to add this particular conversation to our May lineup. And it had to be in May because today we are talking about Your Fat Friend, the documentary about our beloved

, which I know so many of you have been dying to see.Your Fat Friend is streaming online at Jolt.Film until June 17!

I know Aubrey needs no introduction to most of you. But she is the author of What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat and You Just Need To Lose Weight and 19 Other Myths About Fat People. She’s also co-host of Maintenance Phase and you can catch her Burnt Toast episodes here and here.

And today, I am so thrilled because I’m chatting with Jeanie Finlay, the director of Your Fat Friend, who followed Aubrey for six years to make this film.

is one of Britain’s most distinctive documentary makers, and has made films for HBO, IFC and the BBC. Whether she’s inviting audiences to share the extraordinary journey of a British transgender man pregnant with his child in her film Seahorse, or onto the set of the world’s biggest television show for her Emmy-nominated film Game of Thrones: The Last Watch, all of Jeanie’s documentaries are made with the same steel and heart, sharing an empathetic approach to bringing overlooked and untold stories to the screen. She is also just an absolute delight of a human. RELATED CALL TO ACTION: The Campaign for Size Freedom is working to get laws against weight discrimination passed in New York and Massachusetts — and they need us to contact our reps TODAY.

For legislation pending in both places to move forward. Here’s a script and contact info. And here’s more info on NAAFA and the Campaign.

PS. If you’re enjoying the podcast, make sure you’re following us (it’s free!) in your podcast player! We’re on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, and Pocket Casts! And while you’re there, please leave us a rating or review. (We like 5 stars!)

Episode 143 Transcript

Virginia

Look, here’s Aubrey right up behind me on the wall.

Jeanie

Oh my goodness!

Virginia

This was the postcard you all handed out at the Tribeca premiere and I just loved it so much, so I just like having it up there. It was a really moving experience to watch it in the theater with everyone at the premiere. I still get teary thinking about it and I’m so excited that more people are getting to see it this month.

Jeanie

Thanks so much, that really means a lot. Showing the film in cinemas has been really phenomenal. I think about the spaces where fat people come together and it’s usually Weight Watchers. It’s been amazing to take over cinemas.

And then there’s a collective experience when people see it online, too. If you’re on the other side of the Instagram or the social accounts when the reactions are coming in, it’s very overwhelming and moving for me as the filmmaker.

Virginia

I can imagine.

Jeanie

I always knew that Aubrey was amazing. But when I think back to that world premiere that you were at, at Tribeca almost a year ago, I was very apprehensive. I made this film completely independently, because it was something I wanted to make. And obviously, you don’t spend six years making a film, if you don’t want it to reach an audience. But I wasn’t sure how it would be received at all.

This is my ninth feature film and I sort of thought, you know what, I’m making this and I don’t care what people think. I’ve got to make it, I need to make it. And then the fact that people have been connecting with the soft and tender bits that I felt when I was making it? It makes me feel very emotional even just thinking about it.

Virginia

I think a lot of people are seeing themselves in it, both in Aubrey, but also in her parents, in the comments other people make in the movie. I think you’re seeing yourself in a lot of different ways that can be challenging and uncomfortable but also profoundly moving.

I think that the experience of that representation is so missing in any other films, TV shows. We don’t see fat life portrayed on screen like that, pretty much ever.

I’ve been thinking about your film in contrast to projects like The Whale. Or even Baby Reindeer, which just came out here—and there’s a big conversation happening about the portrayal of fatness there.

But there are also so many documentaries that are “health” focused, from Supersize Me all the way through Forks Over Knives. And that whole genre feels really problematic to me because people so often view them as objective fact. I get emails all the time —from trolls but also from well-meaning people—saying, “If you would only watch this documentary, you would understand that everything you write is wrong.”

What do you wish people understood about how those kinds of films get made?

Jeanie

It’s a big old subject. And partly, it has to do with the way that documentaries are perceived. So it’s worth giving a bit of context. In the last 20 years, documentaries have exploded. They didn’t used to be seen in cinemas. Netflix wasn’t a thing. There wasn’t a mass audience for documentary outside of PBS in the US. There are a lot of myths about documentary making. One of them is that this is “fly on the wall” filmmaking and you know, I’m not a fly. I’m take up too much space to be a fly.

Virginia

You’re wearing a beautiful rainbow caftan, you can’t be a fly.

Jeanie

What I’m trying to show you is a relationship. I’m showing you my lens. This is authored work. This is the view that I found as this filmmaker—at this point in my career, as a parent, as somebody who lives outside of London, who’s British making this film about an American person, someone who didn’t go to a private fee paying school, all of those intersectional things. As a white lady, as someone who is fat but who is also a small fat person, a problematic mid size queen—all of those things are things that I’m bringing to this.

I want to be fair to the people that I make my films about, but the idea that documentary is fact is kind of silly. Supersize Me is as much about Morgan Spurlock and his bias and ideas about what makes a funny film. His perceptions of what eating McDonald’s is, about his perceptions of food poverty, or his access to food. All of those things play into him making that film at that time. And I don’t know how many people are prepared to examine the paradigm shift of the work that Aubrey has been doing, but also the work that fat activists have been doing for decades, the work that you’re doing. How much of that work is being brought into play when people are making these documentaries? Or are they just reinforcing the ideas that they already had?

I know the power of an interview. And I also know the power of an edit. Documentary is an unregulated industry, so it’s almost like you have to make your own guidelines for proceeding. Now, as an independent maker, it means that there are choices I make in the finance that I raise for my films, but also in the ways that I make film.

I use non-binary consent in my filmmaking practice, which means that consent is never taken for granted. It’s something that we discuss at all stages of the process because the traditional way of making films is you deliver someone a contract that is the length of War and Peace and just ask them to sign their name to the end and then whatever. That means anything you say can be used in perpetuity in all media known now or in the future. And that just sort of doesn’t feel okay to me. Let’s just have a more sophisticated conversation about this or a more open conversation about what it means to tell your story on screen. It also means that there’s mental health supervision on my films. But these things are in my gift, because I wrote the budget and I’m a producer on the film.

But these documentaries which have informed our ideas about “health” have been made under these old models of documentary filmmaking. Which are: You get the biggest characters to give you the broadest brushstroke facts. You never acknowledged that you’re leaning into the bias or the views that you may hold as a maker. Stuff gets fact-checked, but it’s only as good as the fact checker. In something like Supersize Me, is there a responsibility to actually think about the stories or the myths that have been perpetuated as part of that media?

Virginia

To be somewhat fair to Supersize Me, it was made at a very different time in the discourse. It is a much older film. But even the more recent ones, it does not feel like anyone in any production meeting said, should we think about how much anti-fat bias is informing this conversation? Should we name that or give it a passing reference as a concept? I mean, it doesn’t feel like it’s anywhere in the room.

Jeanie

It’s worth questioning that power. We showed this one with Sheffield Documentary Festival last year, which is the big documentary film festival in the United Kingdom. And we won the audience award, which was astonishing and amazing. But I did have a lot of encounters the night after the premiere, which were with thin male documentary directors.

Virginia

I bet those were fun.

Jeanie

They were drunk and crying because they have to be absolved for the terrible things that they’ve all said or done. It was like, Oh babes, no. No, don’t come to me for this.

Virginia

I’m not going to do this for you.

Jeanie

We’ve had a lot of fat audiences flock to watch the film. And later on in the year, when the film broadcasts wider, it’s going to encounter a more general population. And I’m deeply fascinated to see how that works.

I made a film in 2019 called Seahorse which was about a trans guy getting pregnant and having a baby. I followed him—Freddy McConnell—and I was there when the baby was conceived and I was there when the baby was born. But it’s really about the stuff of life, about what it means to live in a body that’s changing, and about his family relationships. I would say that that film is definitely a sibling to Your Fat Friend.

And the experience of that broadcasting at a primetime slot on BBC Two, nine o’clock was extraordinary. Because for a lot of people watching, it was the first time they’d heard the experience of a trans guy articulating his experience giving birth. For some people, it was the first time they’d knowingly heard a trans man explaining what gender dysphoria. The cosmic toothache of dysphoria—what does that mean?

I’m very interested when you take these very personal, particular experiences of one person that can hold a mirror to a wider experience and then you put them in places where millions of people see them.

Virginia

I’m getting nervous just thinking about it, as someone who has had smaller tastes of taking my personal story into the mainstream here and there. It can be rough. I’m not telling you anything you don’t know. But the thing is, is no matter how much control you have over the project—which of course in your case, you had so much control. You’re the filmmaker. But you don’t have any control over what the audience does with the work. And that is always terrifying.

There’s a lot of good that comes out of it, and there’s a lot of darkness. I think it can even be hard to talk about the darkness. There’s this perception that this is the cost of doing business. This is what you have to expect if you’re going to tell challenging stories in public, which almost makes it sound like we asked for it or something.

Jeanie

I mean, I think it’s enormously challenging. I believe in the power of film to help us articulate ideas or thoughts that we may not have had the language to express before. It sounds very grand, like I’m applying that to my own work.

But like when I’m thinking about the experience of Seahorse, I was quite scared. When we showed the film at a festival in Russia, it was shut down because there was a bomb threat. It was enormously scary. And Freddy was fighting in the courts to be named as a parent on the birth ticket, instead of mother. And this had been done in private, it’s not included in my film because it would legally prejudice the case. But a journalist outed Freddy and he ended up on every cover of every single newspaper in the United Kingdom.

Virginia

And the British press happen to be so kind and nuanced in their coverage.

Jeanie

Oh they’re so lovely.

So we had a screening in London and we had this ridiculous situation where we had the paparazzi lining up outside the cinema and we had to escape out of the back door.

But on the other hand, what I would say is, that stuff flares very white hot, it’s like a firework. It happens very quickly. But on the flip side of that, the lasting, the lingering stuff from a film can last a long time.

I’ve been at lots of screenings of Your Fat Friend and I took it to Leeds Film Festival in Yorkshire in the north of England. And two parents stood up in the Q&A, two moms, and said, “My child is trans and I’m here today to say thank you for Seahorse because it helped me understand what my child was going through.” And that was just like oh, my goodness, this is why we do it. Or getting a phone call from my 94-year-old Gran who said she’d never heard of a man having a baby but now she understood it.

Virginia

Oh, good job, Gran.

Jeanie

Roger Ebert, the American critic used to say that documentary films had the capacity to be an empathy machine. And not to sound like Pollyanna, but I do believe in that. I want to make films where you fall in love with the people that you’ve spent time with on screen.

I think the reason why I wanted to make a film with Aubrey—I went off on a mission. I wanted to make a film about fatness because I could see that the conversations were changing. So I set myself this ridiculous task. I’m going to make an essay film, I’m just going to try and survey the way that people are talking about fat now. And it was rubbish. It wasn’t interesting. It was just like a Wikipedia article set to music. Whatever I did with it, it wasn’t quite right. I kept sort of straying into body positivity. And it’s just like, this isn’t about ooh, I can’t wear a bikini.

I’m interested in what other structural things that are in place affect the literal lens that we’re viewing other people in the world. How does that contribute to bias? And how do you make a film that swims in all that messy stuff? How does that show up with your mom? And your relationships?

As soon as I read Aubrey’s piece, I knew I wanted to meet this person, the person who had written her first blog post. And then when I met her family and realized they’re in a really, really different position of where they are with their politics or just their view of the world. And that’s something that anyone can relate to. It’s something I relate to on a personal level. I was like, well, this is totally fascinating. This is where the film can live, this space.

That’s what I’m always looking for. What’s the where’s the space where the film can live? Because someone being interesting or dynamic on screen is not enough to tell a story. It’s just the beginning. Where are we going to go?

And that was a year of trying stuff out, filming loads of things, meeting a lot of people. And then when I found Aubrey it was like, Oh. Here she is.

Virginia

There she is. And then you spent six years with her! I would love to hear what is it like to work on a project for so long and to follow your subject for so long and so intensively?

Jeanie

I mean, this is something that I’ve done before. I love making films. This is the only thing I do. This is my living. And the way to make it work as a filmmaker is to work on more than one project at a time. So sometimes I set a project going and then I’ll go and do another thing. So I started on Your Fat Friend and wasn’t sure what direction it was going to take. And then I put it on hold, because partly because I was very intensively working on Seahorse. Freddy was pregnant, I had the birth to film and edit. And I edit for like six or seven months. So it’s very long and expensive process.

And then I also was embedded on Game of Thrones. The reason why I was able to meet Aubrey in the first place was I was invited to Los Angeles to be interviewed by the showrunners for Game of Thrones. So I just flew over to Portland because it’s an hour flight. I was asked in the interview, why are you going to Portland. And I was like—the film at the time was called Luxury Bitches—I said I’m making this film called Luxury Bitches about fat bloggers.

Virginia

Thats a hilarious title.

Jeanie

The showrunners of Game of Thrones were like, “Go! You’ve got to make that Luxury Bitches flight.”

Virginia

I want a Luxury Bitches t-shirt. Do we have any? Did we get any merch? I would happily wear that. I don’t know if Aubrey would, but I would.

Jeanie

I think she probably would. In the UK, we both bonded very much over the luxury bitch selection of goods at Marks & Spencers.

Virginia

That is peak luxury bitch.

Jeanie

Sometimes films take a long time because it’s really hard to persuade the financiers to come on board. Sometimes they take a long time because they just need time elapsed. Things need to happen.

I used to run half marathons and I sometimes think that making longform documentary filmmaking is like running a half marathon. Sometimes you just have to put one foot in front of another. It’s mile ten, and it’s agony.

Virginia

Aubrey had to live her life, you had to follow her for that long for all the things that happened in the film. There wouldn’t have been enough if you just filmed her for three months or something.

Jeanie

I like making observational docs in that I don’t know what the ending of the film is when I start

Virginia

As a writer, I find that terrifying.

Jeanie

It’s very exciting!

Virginia

The lack of control, oh my God.

Jeanie

Oh, I love it. I like taking risks. It feels like this massive roll of the dice. Is anything going to happen? I just had to trust my gut instinct when I was like, I think we’ve got something. But initially the end of the film was going to be Aubrey revealing that she is your fat friend, the end. Then because of making the other films and then because of the pandemic, we just had this really stretched out duration of making the film, but that actually was like an enormous benefit, because she’d really traveled somewhere in that time and found her voice.

I think the film is about Aubrey becoming visible. Fat is something that is weirdly invisible, you know? Obviously, we’re all having more conversations now but when I first started making the film I just kept thinking how it’s like an invisible mask, but you actually take up more space.

Virginia

People don’t want to look at it or talk about it or name it. They are always talking around it.

Jeanie

I was at Weight Watchers for years and we were not allowed to say the word “fat” out loud. We had to say fluffy.

Virginia

The absolute worst of all the euphemisms.

Jeanie

The worst! It just seemed like this ridiculous thing. Like, we’re all here every week because we believe that weight loss is possible. We’ve bought into the idea that our lives will be better—until I rebelled and left and was like, my life will be the same.

But I started thinking about Aubrey being this anonymous writer. And then she’s words on a page and a picture on the back of a book. And then she’s a voice on the internet and she has a pen name. And then she steps into her name and comes out fully and is seen in the film. The film is the last part of this journey into visibility.

Virginia

I think that is one of the many things that made me cry, as a colleague and friend of Aubrey’s, and who has followed her journey over these years—I just feel so proud. So proud to see what she’s done and to see her own it and be herself in this way. I know that comes with a cost that I don’t think she should be asked to pay or any of us should be asked to pay. But it also is such a gift to the rest of us that she’s putting it all into the world now.

Jeanie

I remember listening to the very first episode of Maintenance Phase. It was during the pandemic, so I was working with Lindsay Trapnell, who’s a Portland based cinematographer, and Michael Palmieri and Donal Mosher and they would just go and film for me when something was happening.

So I knew it was happening, and then I remember sitting in my kitchen listening to the finished episode. I just started texting Aubrey and just going, “I feel so proud!!” I felt so invested. I think Aubrey’s ability to embody a meet you where you’re at politics—she imparts information very elegantly. It’s a light touch. There’s enormous research, but then it feels fun, she’s good company. You want to hear it and you want to listen to what she’s telling you. It doesn’t ever feel like, oh, I don’t have enough knowledge to participate in this or to even listen. It just feels like yeah, I’m going to learn stuff and it’s going to infuriate me and I’m going to laugh my ass off.

Virginia

She’s also incredibly good at making clear that she’s not trying to be the leader of any kind of movement. She’s really good at lifting up other folks and she’s very clear that she’s the entry point. She’s bringing people in and doing it with such grace and kindness and joy. And then like, here’s all the rest of the work that we’re going to get to.

Jeanie

I would say that your work feels very much like that as well. It’s been really great when we’ve been on the road and people ask questions like, what do I say to my kids? Or how do I deal with this? I’m worried about this. And I’m like, I don’t know. I haven’t got the answers. But there are a lot of amazing books out there and one of the books you can read is Fat Talk by Virginia Sole Smith!

Virginia

I appreciate you.

Jeanie

One of the things that we did when we were on the road was that we partnered with independent bookstores, usually queer bookstores, and we had little mini bookshops in the cinemas so people could see the breadth of fat activism and rights.

Virginia

Because there are so many great voices.

Jeanie

Exactly. It’s like, guys, you need to read any and all of this stuff. So we’ve put those on the website. No one is trying to reinvent the wheel wheel here. But I think that there’s definitely a power in showing one person’s experience of navigating all this stuff.

Virginia

What were some parts of the film that people are responding to, that maybe you didn’t expect?

Jeanie

I knew that people would be into Aubrey’s collection of diet books because they are bangers. And the music, I managed to clear—which was an enormous challenge to get—Try The Worryin’ Way this sort of horrific, 60’s girl group song about the benefits of being with a terrible man for weight loss, which is horrendous. But I also hoped that people would connect with Rusty and Pam, Aubrey’s parents. Because for me, they really go on a journey in terms of hearing what Aubrey’s got to say but also thinking about their actions, but also not always getting it right.

There’s a scene with a cake in the film where we we film Rusty, a man who loves his daughter very, very much, and is a great and complicated dude. I think that that scene feels so deeply uncomfortable and powerful to me. Those sort of scenes are the scenes that I love filming. If I feel deeply uncomfortable while I’m doing it, I know that there’s something important to say there.

The reason why it feels good to me is that Rusty keeps on insisting that the cake is sugar-free and gluten-free. Aubrey didn’t ask for a sugar-free and gluten-free cake. He’s doing it with the best intentions. He says it ten times. And it’s sort of that mismatch of intentions. Rusty has made a cake with all of the love that a dad that really loves his daughter could do. And he misses the target so wide. She’s obviously horrified that he’s going on about this and that we’re filming. But what I love about that scene is that they both love each other. And it’s still terrible.

Virginia

It is both of those things at once. It’s a really hard scene to watch. You really you feel it in your bones, like, yep, I’ve been there.

Jeanie

I think those small moments from the people that loom large in our lives can have much more impact than some troll on the internet saying something terrible. My weight has been all over the all over the place and I remember going to a funeral of a dear family member. At that point, I had not seen some of my family for a couple of years. I remember one of my relatives almost knocking themselves out, climbing over a pew to tell me that I looked extraordinary

Virginia

At a funeral?

Jeanie

At a funeral! I was like, please! It was so horrendous in every way. That person did that thinking that they were giving me the biggest compliment.

Virginia

That you would be so delighted.

Jeanie

It is seared on my memory.

Virginia

Well, the film is just spectacular. I am so excited for everyone to see it.

Butter

Virginia

Do you have anything else you’re loving lately, that you want to tell us about for your Butter?

Jeanie

My daughter is now 20, but I love hanging out with her. I feel like it’s an enormous achievement to have a daughter that I not just love, but I look forward to spending time with her. The Butter for my toast is that Studio Ghibli have started making stage shows of their films.

Virginia

Oh my goodness!

Jeanie

They are absolutely magical and extraordinary. So last year, we went to see My Neighbor Totoro on stage. It was it was one of the most extraordinary magical things. I cried all the way through. And next month, we’re going to see Spirited Away on stage and I cannot wait.

Virginia

I love that. Totoro was a movie we watched a lot when my older daughter was in hospital for a long time. It was such a comfort watch for us. That’s a really good Butter.

I’m gonna just give a quick shout out to a favorite fat British artist of mine, Taynee Tinsley. Do you know her work? She’s wonderful. Every time she releases a new round of prints, I end up buying one because I love them.

Jeanie

Oh, what’s her work like?

Virginia

It’s just really beautiful. Mostly femme bodies, nudes, and a lot about mothers and children. I just got a new print of hers that’s just a really beautiful fat nude. What I really appreciate about this one is I think a lot of times in fat representation in general, we see the hourglass fat. And this is a woman with a belly. As you know, most fat people have bellies. It is a common trait of ours. I really love Taynee’s work. It’s just exquisite.

Jeanie

Oh, amazing. I can’t wait to see.

Virginia

I think aesthetically, it’s right up your alley.

Jeanie, this was spectacular. Thank you so much. The movie is streaming right now on Jolt. Tell us everything we need to know so everyone can go watch it immediately.

Jeanie

Thank you so much for having me on. I’m a longtime listener, first time caller, so I’m very happy to be here.

So the film is on Jolt, which is a new platform that that shows the films that really matter. The thing that’s important is it’s for independent films and the people that made the film actually get the income.

Virginia

Oh, that’s a nice change.

Jeanie

It’s a really amazing and unusual change. So, it’s worth amplifying, but it’s just jolt.film. And the film is available for the whole of May, through June 17.

The thing that’s been really lovely when we’ve shown it before is that people send us watch party photos. We really like to see where people are watching and who they’re watching it with because it’s amazing to see how far in the world it’s traveled to and what folks are watching. So that’s just like a little personal thing that really makes me happy, when I see people watching the film.

Virginia

So should people send that to you on Instagram?

Jeanie

We’re just on socials all the time, this is the modern world. So we’re @yrfatfriendfilm and I’m just @JeanieFinlay. But yeah, just tag us in and we’ll repost it on the film Instagram. We love to see photos. It’s brilliant.

Virginia

Thank you so much for doing this. This was absolutely delightful.

Jeanie

Thank you so much.

The Burnt Toast Podcast is produced and hosted by Virginia Sole-Smith (follow me on Instagram) and Corinne Fay, who runs @SellTradePlus, an Instagram account where you can buy and sell plus size clothing.

The Burnt Toast logo is by Deanna Lowe.

Our theme music is by Jeff Bailey and Chris Maxwell.

Tommy Harron is our audio engineer.

Thanks for listening and for supporting anti-diet, body liberation journalism!

Thank you Virginia. It was such a joy to talk to you. Long time reader, first time caller indeed! ♥️

I can find out about doing a community screening through Jolt for the Burnt Toast Community. If this is something you’d be interested in, reply to my comment so I can gauge interest!

Oh I LOVE this idea. Would love others to chime in!

And Jeanie, thank you so much - you’re the best!

A watch party, I mean!

me!

Yes, please!

I’d happily see it a third time!

Yes!

YES YES YES

Yes

I love this film. I’ve seen it twice now, including in a cinema in Dublin with Aubrey for a Q&A, and v excitingly her mum Pam in the audience.

Rusty’s journey makes for a great story, he’s v dramatically shifting his ideas and his bias over the film, and also EveryDad in his well meaning but awful remarks. For me, Pam is so much more interesting and nuanced. She’s engaging so deeply in reflecting on her parenting, her own history and bias, she’s really doing the work. It’s just lovely. It made me think about how it seems like it’s very easy to praise men for doing the bare minimum.

Pam is the MVP!

Oh that's so interesting -- you're right about that gendered dynamic. Pam is an absolute hero of the film.

Would anyone be interested in a Burnt Toast community watch party of this film?? Not sure how we'd organise/run it using Jolt but it could be really fun?!

I would!!!

See my comment above :)

Ooh great minds! Thanks Jeanie

This film really gave me a lot of compassion for my mom.

I gave my employer a lame excuse why I wouldn't be available this afternoon. I couldn't trust they'd get watching a film as a worthy reason. But oh my god, was it worthy. Fabulous. Thank you.

Hero

LOVE that you did that!

I have listened to this interview 4 or 5 times. Your conversation about the power and the hope of film is how I see literature. As I finish my first collection of personal essays, I will reread it several times to ensure that it stands up to what you speak. Thank you.

I just watched Your Fat Friend with my partner, all the way from France ! I loved it and found it very touching. Thank you Aubrey and Jeanie for this ! (also loved the subtitle option, very useful to be sure to understand everything)

This film is magic!

MAGIC.

I’m so glad Jeanie brought up the cake scene because it was really uncomfortable and I was wondering why she used that footage. I assumed he was trying to comply with Aubrey’s dietary guidelines, not that he took it upon himself to get a sugar free, gluten free cake. I guess I gave him too much credit!

Anyway, I love the film and recently wrote a review of it for a local Bay Area site.

Of course I used it! The uncomfortableness is the point. It was a messy situation. People’s lives are messy. Our lives are messy

The small details of people’s lives are THE Stuff. Rather than the headlines.