The Burnt Toast Guide to Division of Responsibility

Untangling the Instagram hype, ableism and diet culture from a few good ideas about feeding kids.

BT Guides are the series where I dig into your most frequently asked questions. We’ve covered: misconceptions about weight and health, talking to kids about anti-fat bias, diet culture in schools, kids and sugar, and how to survive holiday meals (and eating with other people in general).

BT Guides are a free resource, but if you find them valuable, please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription. You can join for just $5 per month (or $50 for the year).

Or you can upgrade to our new Extra Butter tier for $10 per month.

Extra Butters get everything that comes with the usual paid subscription plus a second Indulgence Gospel episode every month, a comp subscription to Cult of Perfect, and a monthly Live Thread with me. Our next one will be next Monday, February 12 at 12pm Eastern. You can ask me anything you like, and we’ll also have a fun Friday Thread-style prompt!

If you can’t make it, but have a question to ask or an idea for a group prompt, you can drop it here and catch up on the thread later. Join now so you don’t miss out!

Division Of Responsibility: Will It Save Dinner?

On September 17, 2013, my first baby stopped eating. I’ve told this story many times (including in my first book), and for years, I would always say some version of, “Division of Responsibility saved us.” It was, of course, a lot more complicated than that.

It is true that my realizing that we could not “make” her eat, or control how much she ate at any one meal, was crucial to making the space she needed to heal and get back to eating by mouth on her own. It’s also true that over a decade later, I simultaneously consider Division Of Responsibility (which we’ll now refer to as DOR) to be the bedrock of how I feed my kids and…I have some notes. Classic DOR is not the right fit for every family. It’s also marketed (by the folks who pioneered it and by many other dietitians and influencers) as a “fix” for picky eating and a way to “get kids to eat their veggies.” But I don’t know how to use family meals to “fix” picky eating or to “get” kids to eat vegetables. I no longer believe those should be our goals.

There is a LOT to say about DOR, and some of it starts to blur over into just how to think about family dinner in general. This BT Guide will focus on the method itself; next month, we’ll get into the nitty gritty of family dinners themselves. (If you have questions today that this guide doesn’t answer, let me know and I’ll tackle them in the next one!)

What is DOR?

When parents hit a wall with a toddler who suddenly drops all their previous favorite foods, or with a preschooler or elementary school-aged kid who wants to live on a snacks and snacks alone, they (we) often find our way to the Division of Responsibility. This feeding approach was pioneered in the mid-1980s by feeding therapist and registered dietitian Ellyn Satter in response to the “clean plate club” school of family dinners, which a lot of us grew up with.

You can read Satter’s official explanation of the approach here. It rests on the premise that feeding is a relationship with parents and children each having specific roles to play.

Parents are in charge of:

When meals and snacks are offered

Where meals and snacks are offered

Which foods are on the menu for any given meal and snack

Preparing (or purchasing) the food

Kids are in charge of:

Deciding how much to eat at any given meal or snack

Deciding which foods to eat from among those offered

Learning to “behave well” at mealtimes

If you’ve never used it, DOR can feel revolutionary or terrifying or both. This is because diet culture has conditioned us to think we don’t know how much to eat (and that any amount of anything delicious is “too much”), but that we nevertheless should be in charge of how much our kids eat, right down to how many bites of broccoli will earn them dessert.

There are really, really good reasons to let go of our need to control how much our kids eat. Here’s how I explained it in Fat Talk:

…the belief that children should eat any food put in front of them, without complaint, doesn’t allow for much individuality of preference. And worse, it frames eating as a moral and a behavioral issue. Kids are labeled early as either “good” or “ba” eaters. And those labels are hard to shake. When the goal of family dinner is clean plates, then a child’s refusal to eat certain foods is perceived as rude, disrespectful, wasteful, or rebellious. No matter what motivation drives it, demanding clean plates is, at its core, a lesson in control. It’s a parent saying to their child, I know what’s best for your boy. You need to put this in your body even though you don’t want to—because I said you should. And this is where the “clean plate club” can become dangerous.

Pressuring kids to eat is also a surefire way to wind up stuck in a power struggle. And research clearly shows that it does not get kids to eat, or teach them to like the experience of trying new foods.

What Does DOR Get Wrong?

DOR doesn’t always meet the needs of neurodivergent families, as Naureen Hunani, a pediatric dietitian and multiply neurodivergent person, explained in this podcast episode:

I do think there is still a lot of value in the child’s jobs in feeding, in terms of deciding whether or not they wants to eat and the quantity. But it’s the what, when, and where that I feel like a lot of people struggle with. Because a parent might think that the family meal table is the best place for the child to eat, but maybe it’s not. I think this is where things get really, really messy, where I have had to sometimes even separate different family members, because it’s just doesn’t feel safe. Or what the other members are eating is just so aversive from a sensory standpoint, the smell. Plus all the demands that come with socializing, when it comes to eating. Some children don’t have the capacity at the end of the day to be able to socialize and, quote unquote, behave well and sit down and all of that.

So for some children, having a little table on the side works better. Or it could be in front of screens, even. For some children that works better because it provides self-regulation and some predictability instead of adding those social demands and all of that. With the what and when and where, we have to really look at the child’s development abilities, feeding abilities, preferences, all of that, and then make the right decision, whatever that looks like.

It’s also very easy to infuse DOR with a diet mindset. If parents are in charge of which foods get served, they might decide to only serve “healthy” food as a kind of backdoor way into restricting treats. We see this explicitly in the way many Kid Food Influencers invoke DOR, claiming that a lunch that offers six kinds of produce and just three M&Ms is adhering to Satter’s principles:

Kid Food Instagram has taught us that we have to retain total control over the family meal experience because our side of the Division Of Responsibility bargain matters more than our kids’ role. So we want that control not because it’s good for our kids (it often demonstrably isn’t) but because it feels like the only way to attain the kind of mealtime perfection that Kid Food Instagram performs. “When influencers translate concepts like Satter’s into oversimplified pastel infographics, they end up conveying the message that it’s on individual parents to optimize our children, fix unwanted behavior, and resolve conflicts in the home around eating,” says Evie. “The clever, peaceful mom is the one who follows the right accounts.”

What’s happening here is both a distortion of DOR and an unveiling of some fatphobia and diet anxiety that has been there all along. Satter’s 1987 book How To Get Your Kid To Eat...But Not Too Much includes a chapter titled “Helping All You Can To Keep Your Child From Being Fat.” Satter’s own perspective and the work of her institute have evolved since then; a more recent post encourages a matter-of-fact, non-shaming response if your child asks “am I fat?” But it’s unclear if Satter has ever fully acknowledged or reckoned with the anti-fat bias woven through her earlier work.

So What Do We Do With It?

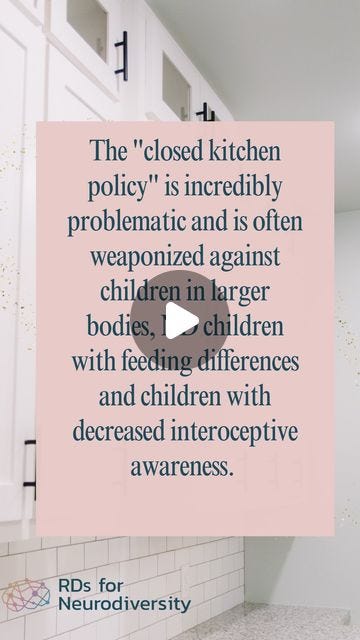

In recent years, Hunani and other pediatric feeding experts have begun to advocate for “responsive feeding,” which uses DOR as a foundation, but also empowers parents to make our own adjustments. Your interpretation of “when and where meals happen” might include afternoon snacks that serve as dinner for younger kids, or meals eaten in the car on the way to activities, or in front of a screen. You might decide that the kitchen doesn’t close between meals at your house, because you want a child in recovery from an eating disorder or other food-related trauma to know that eating is always okay.

Responsive feeding encourages parents to meet their kids where they are, and let go of any piece of the framework that doesn’t serve us—as long as we’re not interfering with our kids’ ability to decide how much to eat, and whether or not to eat something we’ve offered. “To me, that is a hard boundary, and whenever we try to manipulate these (through pressure, coercion, bribery etc…) then we have crossed a line in the feeding relationship that will probably cause problems,” writes

in her deep dive into what works and doesn’t work about DOR. (If you’re really feeling trapped in the weeds of how to navigate a particular facet of your kids’ mealtime behavior, check out Laura's work.) Kids do need structure, but the goal of structure is to make sure they have enough to eat — never to restrict them from eating too much.In my own house, the extent to which we’re practicing “classic DOR” has varied tremendously over the years. Like Laura, I view the children’s right to be in charge of how much they eat as the non-negotiable. But I prioritize their comfort at meals over their learning to “behave well” at the table, which means we now frequently have dinner with books (yes, even an audiobook on headphones) or in front of a Friday night movie. We’ve also had phases where the schedule gave way to grazing (hi, pandemic!) though I’m lately working us back into set afternoon snack and dinner times because I can see how it helps my kids regulate. (I also love a bedtime snack.) I don’t short-order cook, except when I do. Instead, I serve most dinners with a snack plate—a mix of fruit, veggies, crackers, cheese—that often ends up being one child’s dinner.

DOR has not “fixed” my kids, who are not—and never were—broken. It has not transformed them from cautious eaters into adventurous epicureans. But it helps me avoid micromanaging their eating in ways that would override their body autonomy. And this helps my kids feel safe and seen at the table. Everything else can be a work in progress.

The only thing I knew when I had kids was that I didn't want to pass on diet culture and morality tied to food. Add two neurodivergent kids. Meals are pretty much the same now even though they are adults. I'm making dinner now, join me if you want or warm up and eat your dinner later when you want. I will make one thing on each of your safe foods lists. So it might look like: baked potato (child 1), pork chop (child 2), broccoli with cheese for me. You are responsible for the rest of your meal. Child 2 sits with me and eats the porkchop and some raw broccoli. Child 1 eats a cold potato an hour later and a slice of cheese. The goal is cooperation around each of our needs rather than control. It works. Honestly, I don't know why so many parents of autistic kids complain about samefood. (Samefood is the autistic preference to only eat a limited number of safe foods.) Samefood makes life much easier.

I find it so interesting how much we as a society panic when "a preschooler or elementary school-aged kid who wants to live on a snacks and snacks alone." I think DOR can absolutely work and is a wonderful thing!

But it's so interesting because...y'all I'm an ADULT and I totally want to live on snacks and snacks alone. I think we sometimes forget that...getting nutrition and eating veggies and all isn't always a joyful exploration even for ADULTS! Sometimes I eat a salad not because I want a salad but because I know I need to get fiber and vitamins. Which is to say, I have a LOT of snacking sympathy.