You're listening to Burnt Toast. I'm Virginia Sole-Smith and I also write the Burnt Toast newsletter.

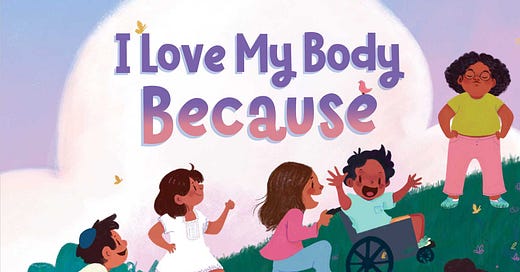

Today I am chatting with Shelly Anand and Nomi Ellenson. Shelly is an immigration rights attorney and Nomi is a boudoir photographer, and together they have written the most beautiful picture book called I Love My Body Because.

We get into the importance of representation in kidlit, the way publishing is slowly—too slowly—starting to change in this direction. And they tell some really delightful stories about how kids and parents are responding to their work. So here are Shelly and Nomi!

PS. It’s the last week to join the Burnt Toast Giving Circle! We have raised over $28,000 and I would love to close that final gap and hit our goal of $30,000. Every dollar goes to flipping the Arizona state government blue — which is absolutely critical in a Post-Roe America.

Episode 65 Transcript

Virginia

Why don't you each introduce yourselves?

Shelly

I'm Shelly Anand and I am a picture book author. I'm an attorney. I'm an immigrant and worker rights attorney. I'm a mother of two. And I'm really excited to be on your show!

Nomi

Hi, I'm Nomi. I'm a photographer and I specialize in a genre called boudoir photography, which is about empowering women in their bodies, connecting with that inner goddess, and all of that good stuff. I have a photo studio in Brooklyn and I'm also expanding. I live in Montego Bay, Jamaica and I'm starting to do photo shoots here, as well.

Virginia

We are here to talk about your wonderful book I Love My Body Because. It is very beloved in my house already, I can tell you. So I want to hear the story, how do a boudoir photographer and an immigrants rights attorney decide to write a body positive kid's book?

Nomi

It seems so random, but it really was such a moment of flow. Shelly and my sister are best friends from Wellesley College and when Shelley's first book came out, we were hanging out at the beach. As a boudoir photographer, I'm constantly talking to women about their bodies and how they feel about themselves, their sensuality. So much of what I say to them is what you would say to that inner child in all of us. And I said to Shelley, “What are your thoughts about doing a body awareness children's book?” and she was automatically like, “Let's do this.” It just all felt like it was in the stars and meant to be. That's the short version of how it all happened.

Virginia

Shelly, I would also love to hear how you came to do Laxmi’s Mooch. And how you see these books as connected?

Shelly

I didn't set out to become a picture book writer. I've always loved stories and storytelling, and reading, but I think becoming a parent and being a brown mom in the Deep South, raising biracial children—my kids are half Indian, and my husband's a white white man from Wisconsin. We were looking for books that were important to us, that instilled values that were important to us. So children's literature became something that I got interested in as a mom. I was on maternity leave with my second when a friend of mine from from college who lives close by, who's also South Asian, also raising hairy Desi kids in the south, called me and said that her daughter had been teased in school for having a mustache. And she was only six years old.

It just was a very poignant moment for me. I had given birth to my own daughter who inherited my hairiness and it just brought back a flood of memories of body hair removal and being teased myself as a young, brown, hairy child. And really thinking that I wanted it to be different for for my children and for all children, that that they not go through what what we went through and it really be a choice that you know, you don't feel this pressure to wax or bleach or thread a part of your body off because other children or other people are teasing you or because that's what Western society is pushing on you.

And so that's where the idea for Laxmi’s Mooch came from, I wanted to create a story about a young girl discovering her body hair and hair removal not being the answer. I started reading a bunch of kidlit and joining writers groups and things like that and that's how Laxmi was born.

So when Nomi was like, “I'd love to work with you on a book about body positivity,” it felt like a natural next project for me, because they are very much connected. Laxmi’s Mooch is very specific about body hair positivity. But when Nomi and I were talking about this, there weren't a lot of picture books out there on body positivity and specifically fighting fatphobia and dispelling the word fat being something negative. Like Nomi said, it was a very different process than writing Laxmi’s Mooch. Laxmi had more of a narrative and this is more like an ode to your body and all the amazing things our bodies can do—not just physically but intellectually. That we can read and we can learn and we can take care of ourselves. It really just poured out of us and it was a very, very healing. Both books were a very healing experience for me.

Virginia

Oh, I bet, I bet. I work particularly in the anti-fat bias space. And the body hair conversation does not come up nearly enough. I was thinking the other day, my kids have—because I'm their mom and we talk about this stuff all the time—they have really good fat positive vocabulary. But they've seen me shave my legs or tweeze my chin hairs and been like, “What are you doing?” And I'm like, Oh, I don't have the narrative I need for this piece. This is another part I need to work on.

I'm always just like, “It's a choice, you don't have to do it.” But I feel very panicked in the moment, realizing I haven't thought about it. So, I love that you are giving us language and giving us a story that we can use to have these conversations. And not just when you're being barged in on in the shower, when I don't do my best parenting.

Shelly

I mean those are the moments, when when our children come to us, in the shower or on the toilet.

Virginia

It’s like, Okay, let's do this.

Shelly

Let's have this conversation. Yeah, absolutely. Uma, my daughter, now asks me, “Why are you shaving your legs?” Because of this narrative that was created when she was born around being being proud of your body hair. She is kind of like, “What are you doing? Why are you removing your body hair? You don't have to do that.” I'm like, Okay, Uma. Thank you.

Virginia

It’s so cool to see that happening.

It sounds like this was like a real mind meld of a process. How did you each think about what bodies you wanted to represent in the new book?

Nomi

What we were thinking about with different bodies is anchoring in the gratitude for what our body enables us to do. And anchoring in that respect, and that love, and that feeling of celebration, because it is such a gift. Often, everything in the outside world can make us feel negative towards various aspects of ourselves. Creating vocabulary around what's positive and what feels good, enables a new kind of conversation to take place.

We would receive sketches from Erika Medina, our illustrator—she really did an amazing job—and we would be like, “We would love to see this representation and that representation,” and just making sure that it was visually aligned with what we felt in our hearts. While we were writing it, we were definitely thinking about the visuals of the words. For us, it was very intertwined. We wanted the words to be meaningful, but also for the book to evoke a certain kind of imagery.

Shelly

Two books, in particular really inspired me. They're not children's books, but they both address children and perception of bodies. The the first book was Roxane Gay's book Hunger. Something that stood out to me was her talking about children looking at her and pointing at her and being like, “Oh my God, that woman is so fat” and being horrified. Thinking of myself as a parent, but not wanting my children to ever do that to another human being.

[Virginia’s note: This piece is a good read for strategizing on that kind of comment.]

And then Sonya Renee Taylor's book, The Body Is Not an Apology. She talks about children having this sense of joy and wonder and curiosity about their bodies that goes away, and is eroded by messages from the culture about having to look a certain way, having to be skinny and light skinned and blue eyes, and blonde hair, all of that. And I, unfortunately, like so many people, grew up in a fatphobic household and a fatphobic culture. It's actually something I'm starting to think about that's specific to South Asian culture. We have a word for fat, “moti,” and it's pejorative. And it was a word that I feared. It was so negative for me. I think having my children and the pressure that postpartum people feel to have their bodies somehow go back to the way they were before giving birth to other human beings.

Virginia

Because that’s a realistic goal.

Shelly

I mean, that had a huge impact on me. And not wanting my kids to have to go through what I went through in terms of being so mean and self-critical to myself. So there were things in this book that were really important to me, like talking about stretch marks, right? And how they're tiger stripes. Those were things that were really important for me. Because I have these stretch marks now and I see them as a sign of my strength that I carried two human bodies in my body. I think children are taught that there are things about their body they should be ashamed. When in fact, they're quite beautiful, and they should be celebrated.

Even though this is a children's book, it's very much a book for everyone, not just children. It's a book of, like Nomi said, of gratitude. This phrase, “I love my body, because…” can be a gratitude practice, and a reminder, when you're feeling unsure, or insecure, or whatever. Just reminding yourself, I love my body because it helps me move through the world. It helped me start that practice, writing this book, creating that gratitude practice for myself.

Virginia

I'm just thinking too, as you're talking about these inspirations and the wonder that Sonya Renee Taylor talks about that comes so naturally to kids. Little kids—like three or four year olds before the world descends on them in this way—don't feel like they have to justify these things about their bodies, right? They don't feel like they have to give a reason for having stretch marks. It can just be that you're growing or this is your body. We, as adults, have learned this other language of needing to say, “Well, the stretch marks are because of pregnancies.” Some of my stretch marks are just fat, you know?

And I love this idea of starting in this place of gratitude and meeting kids where hopefully at least some of the kids reading this book still are, in this place of “of course, I love my body, why wouldn't I love my body?”

That's so powerful to think about how at some point, however fleetingly, we all started there.

Shelly

You're exactly right. All of us have signs of our growth and our development and we're told that it has to look a certain way. Like, for some reason, having a mooch or a moustache at two or three is okay, but at 12 and 13, it's not. I went through my mother putting bleach on my skin and trying to turn my hair blonde. So unnatural. And I think it was her way of protecting me, but I think it has to be a choice. And it has to be something that a person wants to do, versus “This is what I have to do to make myself acceptable.”

Nomi

With kids, these neural pathways are being highly developed and we want to be building up that muscle memory of feeling good about their bodies. When they're met with that resistance of the negative narrative, they build that internal muscle that much more where they're able to actually think about it for themselves, rather than just accepting what they've been taught.

Virginia

What I really love about the book is that you do expand this idea of body beyond just physical to talk about intellectual gifts. It takes the focus off the aesthetic completely, right?

Nomi

Both of my parents are rabbis and I grew up with a sense that our external bodies were not the most important thing at all. Not that we were like schlumpy, but it definitely was not about pop culture and whatever the trends were growing up. So when I started doing fashion photography and I saw that the focus was so based on the external, I was like, “There's a disparity here.”

There's a disconnect between the value we place on our external looks—even though there's value to that and it's okay to want to feel good externally. I think we lose that conversation. Because we get so stuck in this fat skinny/binary convo versus like, actually, what does it mean to self care and take pride in this external, in our looks, versus this internal. That's how we're able to actually live our lives and be connected more to our internal souls and everything.

Shelley

Growing up as a woman, in any culture, but in this culture in particular, there's so much emphasis on having to be beautiful or considered beautiful or being attractive. It's certainly an aspect of South Asian culture, as well, that's pretty problematic. We want kids to be thinking about what our bodies are capable of —beyond whether or not someone thinks we're pretty or cute or handsome. And we're capable of so much, right? The way we can move through the world, the way we can read and learn. We talk in the book about building bridges and skyscrapers. The possibilities of what we're all able to do is so much more than our physical appearance. That's definitely important to me. I'm very mindful of what we say, especially to girls. “Oh, you're so pretty,” is the first thing that will come out of someone's mouth about a girl versus her intellect versus her capabilities.

Virginia

You also have kids using wheelchairs and you're speaking to mobility on a lot of different levels, which I appreciated.

Nomi

We have a child with a hearing aid, too!

Virginia

That's great. I'm curious to talk a little bit too about how you feel publishing is doing on this front. Book publishing in general is super white, super not evolved on a lot of these issues. As recently as like three or four years ago, when parents would ask me for book recommendations, I felt like I had nothing to give them. And now we have your beautiful book, we have Tyler Feder, we have Nabela Noor. In the picture book space, I feel like we are starting to make some progress. I mean, not enough. But I now have a list of like eight books I can put on the website, as opposed to one that was self published by someone 20 years ago. What do you think is changing?

Shelly

Yeah, I definitely think there's a change. I think a lot of writers in the social justice space are looking to children's literature as a space to start having these conversations because that's when ideas and values are formed. I mean, there have been studies showing the percentage of books that feature children of color being so low compared to picture books about animals talking and things like that.

Virginia

Yes, we have more books about snails or something than about Black kids.

Shelly

And I think, more and more, authors of color are wanting to create narratives that are stories that children walking into a bookstore can relate and see themselves on the cover of a book and messages that are important for all children to learn. When I wrote Laxmi, I wanted something that was going to be empowering for hairy, brown girls all over the world. And I think more and more authors are wanting to do that, and publishers are seeing the value of that. I think we're recognizing as a culture that there's so much unlearning we all have to do from how we were socially conditioned to think about ourselves and about others and the value of starting really early, starting as young as you can with with reading these books. It does make a huge difference. I mean, I didn't believe it, but when Laxmi came out, people were saying, “Oh, my gosh, my kid discovered they had leg hair and is really excited.”

Virginia

Aww, I love this.

Shelly

And same thing with I Love My Body Because. Erica’s illustrations are phenomenal and kids are seeing themselves in this book, like, “Oh, that looks like me.” Or being able to be inquisitive and asking questions, like maybe they haven't seen someone in a wheelchair before, but then they're seeing it in a picture book. That's an opportunity for caregivers or teachers to have have those conversations about the diversity of what bodies look like. I think more is needed, right?

There's this book Beautifully Me which is about a Bengali South Asian girl.

Virginia

Yes, that’s Nabela Noor’s book!

Shelly

There has to be a point that we get to where you see a child, a fat child, and the book is not about her fatness or his fatness or their fatness and it's just about them going trick-or-treating or just about them playing. I think we have that discussion a lot as authors of color. There doesn't always have to be a book about our our struggling or us being teased or us having to confront oppression, right? We can just be kids. So I think that's the future and that's the next step that we need to get to.

Virginia

Completely agree. I do love Beautifully Me. But now I just want to follow that character doing something completely unrelated to how she looks.

Any other fun responses you're getting from parents or kids when they're seeing the book and seeing themselves?

Nomi

I have several clients who are teachers who brought the book to their classrooms and they've sent me these really adorable drawings of what the children love about their body. Shelly and I are actually in process of developing some curriculum and worksheets to help people who are reading the book to others to have the conversation. Because it's about reading the book, but it's really about the discussion that flows from reading it and continuing that conversation after you're done turning the final page.

Shelly

We we went to a local library here in Georgia, in Lilburn. We read the book to the kids and to the families. And at the end, whenever we're reading the book, even at home, the last phrase is, “So what do you love about your body?” And we turn that question to the audience. And this boy, he must have been eight or nine years old, he said, “I love my body because I'm Black and I’m me.” And he was there with his younger siblings and it was just so, so powerful. So beautiful. And you know, his mom was there, smiling with pride. That's why we wrote the book.

Butter for your Burnt Toast

Shelley

I have a pretty robust mental health self care regimen which includes a therapist, a life coach, but I've added in incense. I light incense in the morning and it helps me relax and set the mood for the day. I've gotten into crystals, as well. And then I recently started going to this local healing arts center. It's called Decatur Healing Arts and there's a woman there who's trained in Reiki and in gong baths which is like sound baths and it has been amazing. It has changed my life.

Virginia

So wait is a sound bath… I've been confused about sound baths for a long time, so I'm glad you brought this up. Is there water involved? Or you're bathed in sound?

Shelly

You’re bathed in sound.

Virginia

Thank you for clarifying what was obviously a dumb question.

Shelly

No, not at all. I mean, I didn't know anything about it. But I was talking to my therapist and I was in like, a difficult space with my my day job, and I needed to find release. She's like, “You're Indian, have you tried ayurveda? Have you done any of these things?” I'm like, no, I haven't. And I've been taking SSRIs for forever.

Virginia

Also a useful tool.

Shelly

Yeah, SSRIs are great. I'm very pro but I needed more than that. And gong baths, incense, and crystals have been a great addition to my mental health regimen. So I wanted to share with folks.

Nomi

So my butter on toast situation is I found this journal called the Cycles Journal, which allows you to track your flow with the moon. I'm interested in continuing this internal work as a way of empowering women to view the things that maybe have made us feel less than, like getting your period is a negative and being like, actually, how can we harness our flow as a way of empowering ourselves to live our best lives, basically. So, this woman named Rachel Amber created it. And you can track where you are in your cycle with the moon and all the different ways to kind of check in with how you're feeling, what your body is doing. I'd highly recommend it.1

Virginia

I love anything that helps people understand our bodies, more especially stuff like menstruation, which has such a ridiculous taboo.

My recommendation this week is a gardening recommendation—I don't know if either of you are gardeners, but my podcast listeners have to indulge a lot of gardening talk. And where I am, in the Hudson Valley, it is now Dahlia season. Dahlias are native to Mexico. They are a spectacular, spectacular flower. We have to plant the tubers in the middle of May. And then you really wait all summer because they have to like grow up from just a root. They start to bloom at the end of July, but they really hit their stride in September and October. It is just something I really need in my fall because I don't have seasonal depression exactly, but I definitely have seasonal anxiety. I am not someone who likes like traditional cliched fall things like pumpkin spice and all that because it just means the end times are coming. That is not exciting for me.

But realizing that I could grow dahlias and still have really spectacular flowers in my garden at this time of year helps me. Now I really look forward to September and October. Last year, they even bloomed into November. So, fingers crossed for a late frost this year.

Thank you both for being here. Again, the book is I Love My Body Because. Tell listeners where else they can follow you both?

Shelly

You can follow me on Twitter at @maanandshelly. You can also follow my organization, Sur Legal Collaborative which is a nonprofit immigrant and worker rights organization at @SurLegal_ATL and that's the same on Instagram. And then my Instagram is @LikhoShelly. Likho means ‘to write’ in Hindi.

Nomi

The best way to see what's happening is my Instagram @boudoirbynomi. It's a place with my photography, but I also talk a lot about mindfulness and getting more in touch with your body. Then also I have another Instagram handle, @nomifoto, and that's where I also post stuff about the book and just some other things going on in my life. So Instagram is the best way to see what's up.

The Burnt Toast podcast is produced and hosted by me, Virginia Sole-Smith. You can follow me on Instagram and Twitter at @v_solesmith.

Our transcripts are edited and formatted by Corinne Fay, who runs @SellTradePlus, an Instagram account where you can buy and sell plus size clothing.

The Burnt toast logo is by Deanna Lowe.

Our theme music is by Jeff Bailey and Chris Maxwell

And Tommy Harron is our audio engineer.

Thanks for listening and supporting independent anti-diet journalism!

We just want to acknowledge that not everyone with a uterus has, or can have, or wants to have a regular monthly menstruation cycle. And that is totally fine and totally normal!

Share this post