You’re listening to Burnt Toast! This is the podcast where we talk about diet culture, fatphobia, parenting and health. I’m Virginia Sole-Smith, and I also write the Burnt Toast newsletter.

It’s time for another community episode! As I said in our first community episode on anti-diet resolutions last month, this is a new format we’re experimenting with and I’m thinking of these as Friday Threads for your ears—a chance to hear each other’s stories and perspectives and learn from each other.

This month, we’re tackling the new AAP guidelines for the treatment of pediatric ob*sity. This is a story I’ve been following for weeks now; I wrote about it for the NYT and then more extensively here on Burnt Toast, and have also been getting lots of media requests from other outlets. And it has been pretty fucking exhausting, to be honest—because it’s hard to be faced with this brick wall of anti-fatness from an organization we’re supposed to be able to trust, and because, as a semi public figure, it’s also a lot to then deal with the other brick wall of anti-fatness that comes from people on the internet when we talk about these issues.

So I want to be clear: This episode is not interested in both sides. The conversation we’re having here today is intended to articulate the harm we are experiencing, as fat people, as parents, as humans concerned about the safety of other humans.

I also want us to start brainstorming ways we can advocate for change, both on a broader scale, and in terms of our own interactions with healthcare providers. To that end, Corinne reached out to some expert voices we trust in fat advocacy and the eating disorder community, to give us some bird’s eye view perspective as well.

Here’s Dr. Rachel Millner, an eating disorder therapist and fat activist, who previously visited the podcast to talk about the relationship between fatness and trauma. I really appreciate how Rachel roots the problem here in the wild power imbalance that exists between doctors and other medical authorities and fat patients:

I think it's easy when we see a long document with lots of references and a list of authors who are physicians or in related fields to make the assumption that the document is complete and actually rooted in science. And that the document is including all of the available research and not just telling one side of the story. Unfortunately, with this document, they are only revealing some of the information and not all of it.

One of the really obvious omissions is that they do not list in this document, the ways that the authors financially benefit from bariatric surgery, medications, and weight loss programs for children. They don't tell us. This document does not disclose the financial investment or benefit that these authors have.

It also doesn't include all of the research. And a lot of the research they did include is really not adequate, not high quality research studies. I think there's probably a piece of them that know that a lot of people are not going to go through all of the references. But if you do go through the references, you see where they neglected to include so much important information.

Corinne did a lot of work on the financial piece of this when we were first getting our arms around this story. Here’s a conversation we had about this back when my NYT piece first ran:

Corinne: I looked into all of the authors of the paper and the main thing that stood out to me was everyone has a financial interest in weight loss surgery. Everyone works at or founded a clinic that does weight loss surgery. So, it's just very complicated. And that doesn’t count as something you have to declare.

Virginia: Yeah, I think people don't understand that you can be an author on a paper saying that bariatric surgery is good and should be done more and you can make most of your livelihood as a surgeon who performs those surgeries. That is not seen as a conflict of interest, right? Because you are an expert in the field. And that feels really, really tricky.

Corinne: You only have to change that a little bit to see the problem. Like, “I'm a plastic surgeon. I'm recommending everyone get plastic surgery.” That sounds like a conflict of interest.

Virginia: Right, hammers find nails. And maybe it would be different if we had socialized healthcare and surgeons didn't make so much money from these procedures. If their financial gain was less concretely tied to their ability to sell their services, but doctors are selling consumer services, as well as saving lives or promoting health or whatever grander mission we ascribe to that profession. They are also in a consumer facing business and that is super complicating. And so in a perfect world, they are paid the same regardless of whether they perform the surgeries or don't perform the surgeries, which is sort of impossible to imagine. Or you would only have this research done by people who don't actively benefit directly from the things they're studying.

Corinne: Right. And also, financials aside, if the point of the study is to determine whether or not kids should be having weight loss surgery, and you already believe that weight loss surgery is a good thing, you're coming into that very biased. It's not like we're just selecting 10 random people and asking them to consider the literature. These are all people that have already decided that weight loss surgery and weight loss drugs are a net good.

I also appreciate that so many of the experts we reached out to were very willing and eager to name the potential for harm. Here’s Rachel again:

I want to be clear that these recommendations will cause eating disorders. Usually I say things like contribute to eating disorders, because we know that eating disorders are complicated and there's probably a combination of factors that lead to the development of eating disorders. But I have no doubt that these guidelines will absolutely cause eating disorders.

I've never met a fat adult who found a focus on their body size to be helpful. Not once. Every adult I've met who was a higher weight kid has named that focus on their body size, focus on weight loss, lead to shame, self hatred, a lifetime of dieting, a lifetime of harm, not ever feeling better, not ever, having more body satisfaction, not ever having more body trust, and the vast majority of time, not ever leading to a smaller body. So this idea that somehow supporting weight loss in kids is going to lead to them feeling better about themselves is just not accurate. It's just not true.

And here’s Elizabeth Davenport, a dietitian who specializes in family feeding and eating disorder prevention, and the co-author of the SunnySide Up Nutrition blog and podcast:

The Academy of Pediatrics guidelines are so awful that it's hard to even know where to start. So many kids are going to be harmed. Research shows that one of the biggest predictors developing an eating disorder is dieting, and these guidelines are telling physicians to tell kids in larger bodies to diet and to tell parents that that's what their kids need to do.

I can't even count the number of clients I've seen in my career that have come into my office because a pediatrician made a comment about their weight. No child should be told that their body is wrong. And sadly, that's what the Academy of Pediatrics guidelines are doing: Telling kids their bodies are wrong.

OK, we’ll hear more from the experts later, but now I want to get to your stories. As Elizabeth says, shameful comments from a healthcare provider can live rent-free in your head for decades, as Lia knows:

It took me a really long time to realize that the damage done to my mental health in being ashamed of my weight and being afraid of going to doctors and feeling like I was failing at something because of my weight was much greater than any damage to my physical health that may have come from my weight. And this is obviously before doctors were told that they could prescribe weight loss surgery or weight loss drugs.

I also really appreciated that my dear friend Amy Palanjian, who regular listeners know well from previous podcast episodes, reached out to talk about what these guidelines mean for her as an eating disorder survivor and as an influencer trying to make ethical content on Kid Food Instagram:

It's taken me a while to even be able to acknowledge the guidelines because it's felt like a personal attack. I was a straight size kid on the edge of being in a larger body and wound up with a 15 year eating disorder because by the time I was 12, I was deemed too big, and also too slow, by adults around me. I don't remember my doctor being in that group, but I can't imagine how much worse it would have been had she been.

I feel like my family, some of whom are in larger bodies, are being personally attacked now and targeted with this. I cannot understand how “experts” can lay out the research and explain how weight loss pursuits don't work, and then double down on it as the solution. I also don't understand how it can be offered as a solution if it's not actually accessible or affordable to the majority of the families.

I worry about how this will potentially be monetized by influencers online.

I worry about how much harder this will make feeding kids in general.

And I don't know how to feel about all the other AAP guidelines I have long quoted as I feel like they are now not a very reliable source of information. I clearly have a lot of feelings about this.

Amy isn’t the only parent wondering whether we can trust the AAP guidance in general now. I think the AAP has done a lot of good, but I think this is a fair question. Here are Ellen and Katie:

On top of all of the concerns and outrage that I have, that so many of us have, I find myself wondering how I'm supposed to still consider the AAP a voice of reason and trust.

This isn't the first time I've questioned their guidance. For example, I think they recommend that you keep an infant in the room with its parents for up to a year, is what they recommend. With my son, we lasted eight weeks before we moved him into his nursery, and it saved my mental health.

So I'm familiar with going against the grain when it comes to the AAP’s recommendations. But there's something about these recommendations that just absolutely reeks of profit seeking, of ignorance disguised as empathy, of seeming to care about our children, while actively refusing to acknowledge the mountains of evidence around eating disorders, and anti-fat bias, and all of the harm that those things can cause at any age.

I think if we've learned anything, during the pandemic, we've learned about the precariousness of science in our culture, and the fragility of trusted medical voices. We don't need more medical institutions to be this out of touch with reality because it runs the risk of more people abandoning science, of ignoring actual sound recommendations that do exist. Parenting is hard enough.

It just makes me sad and my eyes are watering now just thinking about it all. I am sad for the little girl that I was, and the harmful impact that these guidelines would have had on me in a world that was already so critical, and so quick to want me to change my body. And I'm really sad for my own kids. Now as a mom, for whom I've done so much work on myself to be a better more supportive parent. And all the work that I've done just to support them differently than I was. And it feels like all that work I've done is for naught. If these external influences, including people with quote authority, are so contrary and loud.

So my two kids are under four. And I have navigated a global pandemic, a formula shortage, infant and child pain reliever shortage, and more. And each event causes me to lose trust in these institutions that I thought were supposed to work for and with me as a parent and not against me, and I feel like now I'm adding the AAP to that list of institutions that have lost my trust.

Lots of you have told us how these guidelines make taking your child to the doctor feel unsafe. Here are Kate and Sarah with their stories:

As a parent of three children, two daughters and a son, I am increasingly concerned about taking my kids to the doctor in this environment.

As an adult, I refuse to look at the weight when I’m at the doctor, I refuse to let them talk to me about my weight when I'm at the doctor. I have a history of eating disorders and exercise addiction and I can't have a scale in my house. So going to the doctor is a fraught experience for me.

I hate that they weigh my children when they go to the doctor. And at my last appointment, I went to with my teenager and my 11 year old. My teenager wanted to meet with the doctor by herself to talk about her periods and stuff like that, she didn't want her little sister in the room. And afterwards, she was really kind of upset about the appointment. And she said that the doctor talked to her about her BMI. I was absolutely horrified. I'm now having to decide whether I talk to the doctor about it or if I switch doctors again. I am really nervous about taking my kids to the doctor right now. And I think that's really sad as a parent. When they were little it was a it was kind of a joyous experience getting into check in on how they're doing, how is their health, and now I look at it as kind of a hostile situation.

I worry all the time that one of my daughter's earliest memories might be a doctor telling her that she is overweight, too big, too fat. From the very first well visits that I took her on as a baby, as an infant, we were told that she was abnormally large, too large, too big. I was asked, as her mother, what was I feeding her. I was told that my answers weren't sufficient. I saw in her medical charts that the doctors didn't necessarily believe me or my husband. We tried alternating who was taking her to see if we would get a different reaction out of the doctors. We went through three doctors, three pediatricians. And they referred us to multiple different specialists, nutritionists, endocrinologists, and we had many sleepless nights worrying, was there something wrong with our child? Our only child, our first child.

Every specialist that we finally got in with laughed at us. Kindly, they said, “Why have you brought me a fat baby? There is nothing wrong with this child. I have other patients to see. Thank you so much for coming in.”

The irony is that all this time, my daughter had a very serious rare condition that was being completely overlooked. She had a skin condition that was keeping her up nights. She eventually went on to develop asthma. And I believe that the doctors focusing so much on her weight caused them to completely disregard what I was telling them was a problem. The only recommendations the doctors were giving me were to take her to specialists to reconsider how much I was feeding her. I'm still getting over how traumatizing the experience was as a new mom who was suffering from postpartum anxiety.

And here’s Oona Hanson, an amazing parent educator and eating disorder recovery advocate who I learn so much from:

I can't stop thinking about the toll these medications and weight loss surgeries will have on children in terms of their GI system. Knowing the side effects of these interventions, all I can think about is the emotional and physical torment more kids will endure in ways that will have an immeasurable impact on their self image, their relationships, and their ability to learn. This cruelty disguised as health care is appalling. It's one example of the way prioritizing shrinking a child's body temporarily seems to matter more to this committee than the child's actual health and wellbeing.

I'm also thinking about all the kids out there whose parents aren't listening to this podcast or reading this newsletter, who simply don't know to resist a doctor's recommendation, or who have doubts, but don't feel safe questioning the authority of a medical professional. These new guidelines will disproportionately harm the most vulnerable kids, kids of color, kids with fat parents, kids living in poverty, kids whose parents are immigrants, and so many other marginalized identities.

What really boggles my mind is that the doctor's office already wasn't a safe place for kids in terms of attitudes toward bodies food and exercise. Comments from the doctor are already one of the most common eating disorder origin stories. This happened to my own kid, and it's happened to so many other families that I've worked with. These comments from the doctor aren't just part of the catalyst for the eating disorder. They help fuel the eating disorder and complicate recovery. These kids come back to the refrain again and again, “but the doctor said this is what I needed to do to be healthy.”

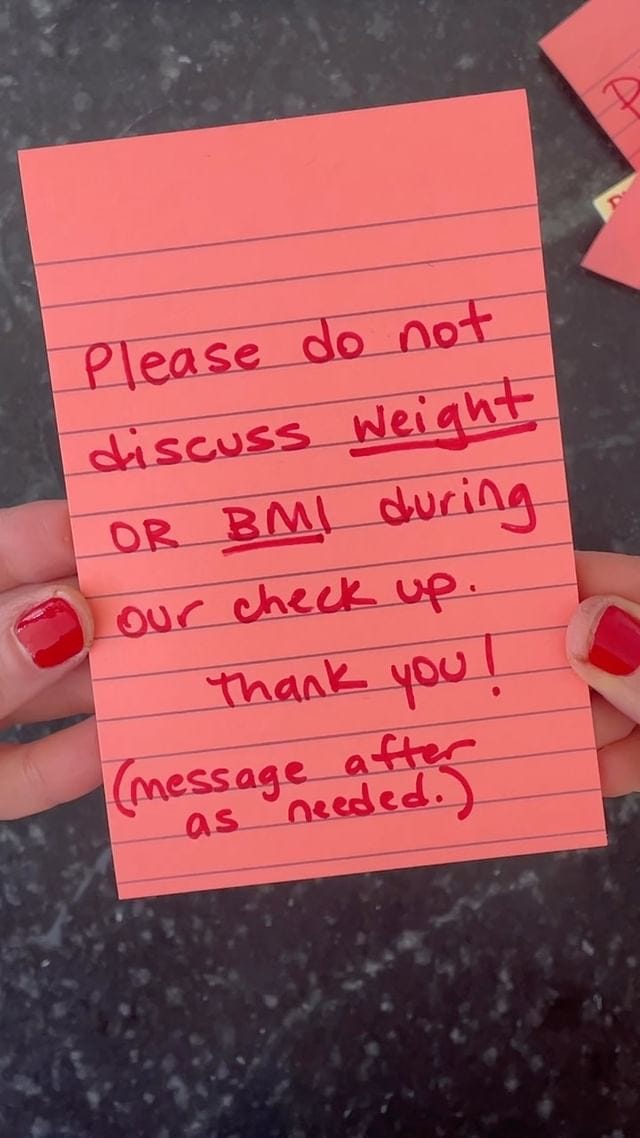

For parents worrying about how to navigate these appointments, Rachel Millner has some good advice:

You can say no on behalf of your child. I believe that children should also be asked and given the opportunity to consent to things that will happen to their body, but they are going to be powerless in this situation, they're going to feel pressure to say yes. And so parents and caregivers need to be able to step in and say no, you do not have any obligation to adhere to what's recommended in these guidelines.

And remember that you’re actually making the “healthy” choice to push back like this. These guidelines aren’t about health, because intentional weight loss has never really been about health. Here’s Calvin’s story:

I think for me, as someone who's, I don't know, medium fat person, large fat, specifically a Black man, living at the intersection of several marginalized, historically oppressed identities. And also someone who's dieted in the past and had several iterations of sizes over my adult life, and navigating my own relationship with my body, and diet culture and really, also engaging with the medical community pretty frequently as a disabled person— It's pretty triggering to see recommendations like bariatric surgery as young as 12 years old.

It brought up for me a recent visit to a bariatric surgeon. I was contemplating the gastric balloon procedure, and have since decided that I don't want to do that. The doctor told me in the visit that I wasn't a good candidate for the balloon, because the ideal candidate is a woman who's going to get married who wants to lose maybe 30 pounds for the wedding. It was just all very toxic and triggering and it made me very upset.

To think that children as young as 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 years old now are going to potentially have to face medical professionals and people who they are trusting to give them sound advice, to engage with this type of dialogue. It's really upsetting.

It’s upsetting because we’re letting capitalism and diet culture interrupt the trust that should be fundamental to a child’s relationship with their healthcare provider. And that’s both dangerous to kids and ignores so many larger issues.

Here’s Anna Lutz, RD, the other half of Sunnyside Up Nutrition and a dietitian who specializes in family feeding and eating disorders in North Carolina:

I think about what it does to a child to be told that there's something wrong with their body solely based on their weight and what that does to a parent to hear that they are failing as a parent, solely based on their child's weight.

This interferes with the feeding relationship, because a parent would feel like they need to possibly restrict their child's eating.

This interferes with the doctor patient relationship.

This interferes with the doctor parent relationship.

And all of this causes weight stigma, which we know has significant mental and emotional and physical repercussions. The guidelines recommend very intense restrictive food and exercise intervention. We know that diets don't work, they even say it in the paper that that doctor should expect weight regain. We know that that weight cycling, that losing weight and gaining weight, has significant health repercussions. And it sets up the child to go to the next recommendation, medications and bariatric surgery. These have severe side effects, but also sets up children to develop eating disorders.

These guidelines once again focus on individuals, putting the blame on individuals and recommending interventions that will actually cause harm and make our children less healthy.

And here’s Rachel again:

These guidelines move kids away from getting to be kids. The side effects the focus on weight loss, going to appointments, getting the message that there's something wrong with them over and over again, is going to mean missing school, missing parties, missing time for playdates and connection.

Part of what's so scary is that these documents they're using the guidelines are using language that makes you believe they are trying to decrease stigma. But you can't decrease stigma while suggesting stigmatizing interventions. It's just not possible.

OK, I want to end with two recordings that really moved me. The first is from someone named Sarah who used to work for the AAP and has many thoughts about what these guidelines will do, and how they represent a huge departure both from where the AAP has been on this issue historically, and what the evidence shows kids actually need.

I am a clinical social worker, although I'm not currently practicing, with a focus on public health and community based resources. I used to work for the AAP, both the National Organization of the AAP and then I was at the Illinois chapter of the AAP for a number of years. When I was at the Illinois chapter, I was actually the Senior Program Manager for child obesity prevention initiatives. This was back in 2012. What my responsibility was when I was there was trying to develop a programming and education for healthcare providers to provide more culturally competent and responsive care when talking with families who had kiddos who supposedly meet the overweight or obese definition.

I've learned a lot in those 11 years since I was there, I would approach things wildly differently if I knew then what I know now. But that being said: Even what we were hoping to do 10 years ago was leading us in the complete opposite direction of what these current guidelines are now recommending, which is so incredibly frustrating because it feels like we are taking 20 steps backwards. And it's heartbreaking for a lot of reasons.

These are not culturally responsive guidelines. They are really unrealistic guidelines. All of the data and the evidence that we presented when we were working on these programs 10 years ago, indicated that the BMI should not be the indicator or the benchmark that we are measuring people's health against.

There needs to be systemic changes to access to food, access to safe outdoor spaces. Reliable basic income, affordable housing, I mean, the list goes on and on and on. But when you are looking and working with families who have all of these additional stressors in their life, and if you totally take out the cultural piece of it, working intensively with a nutritionist and a health care provider to help their kids maybe lose a pound or two is not a priority. And it's going to continue to create an unwillingness for families to continue to engage with their medical home or their primary care provider for any sort of issues, which is certainly not what we want to be doing.

The healthcare infrastructure that we have right now is not set up to accommodate families who need extensive healthcare resources. My recommendation was for healthcare providers to shift the way that they are assessing and looking at a child's health because as we know weight is not the only indicator of health and I feel like this recommendation just shuts the door on that completely. Yeah, it's super heartbreaking. I can't imagine walking my two year old into a healthcare environment and having a doctor or a nurse tell me that my two year old needs intensive weight management. That's gross.

So it is great to hear that there are folks in the trenches actively critiquing these guidelines and advocating for a different approach. If you are a healthcare provider working on this, I would love to hear from you and I would love to know how the Burnt Toast community can support your advocacy.

And last, I want us to hear from Naomi, who has both been there and is now fighting hard for a better way:

As a human being who grew up in a fat body and who started going to weight loss camps when I was 14, and when I think about the damage that five summers of weight loss camp between the ages of 14 and 22 did to me, and that I'm still unraveling at 40 years old.

When I went to weight loss camp at 14, I was so excited about it. I knew that my life would be so different and better if I was thinner because I understood thin privilege, even though I didn't have a word for it. I understood that I would be treated better, that I would get more of what I want in this world, in a thinner body. I just wish that the adults in my life knew better, to give me the kind of support that I really needed, rather than try to help me change my body so that I would be protected from bullying.

In my capacity as an educator and a curriculum writer, I'm working with the nonprofit organization The Body Positive to write curriculum for kindergarten through eighth graders, based on the five competencies of the Be Body Positive model.

I'm in this amazing bubble, doing this work as I think about the possibilities that exist If if we're able to get this into the schools, to help kids stay connected to their wisdom, to help kids see and understand the messages that they get, where they come from, and why and how to resist them, to help kids to see and embrace and celebrate the diversity of humanity, and body size and race and disability in every way that we're different. Rather than to see it as something that's threatening or see it as something that's wrong. It's so amazing to get to work on this every day. hearing about the guidelines that came out. I just can't believe what a weird world it is that we live in where some people think this is truly the answer, to modify children's bodies, versus helping them live full beautiful, complex lives in an imperfect world.

Naomi is right. It is such a weird world. But I’m glad to be fighting for the better way with all of you. Thank you to everyone who sent in recording—I’m sorry we couldn’t include every single one! And I hope you’ll keep talking and keep advocating about this.

Thanks so much for listening today.

The Burnt Toast podcast is produced and hosted by me, Virginia Sole-Smith. You can follow me on Instagram and Twitter at @v_solesmith.

Our transcripts are edited and formatted by Corinne Fay, who runs @SellTradePlus, an Instagram account where you can buy and sell plus size clothing.

The Burnt toast logo is by Deanna Lowe.

Our theme music is by Jeff Bailey and Chris Maxwell

And Tommy Harron is our audio engineer.

Thanks for listening and supporting independent anti-diet journalism!

Share this post